A Detailed Look at Trump's Car Tariffs

Breaking Down the Largest Negative Shock to the Car Market In Years as Trump Hits $350B in Vehicles & Parts with Tariffs

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing, you’ll join over 65,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

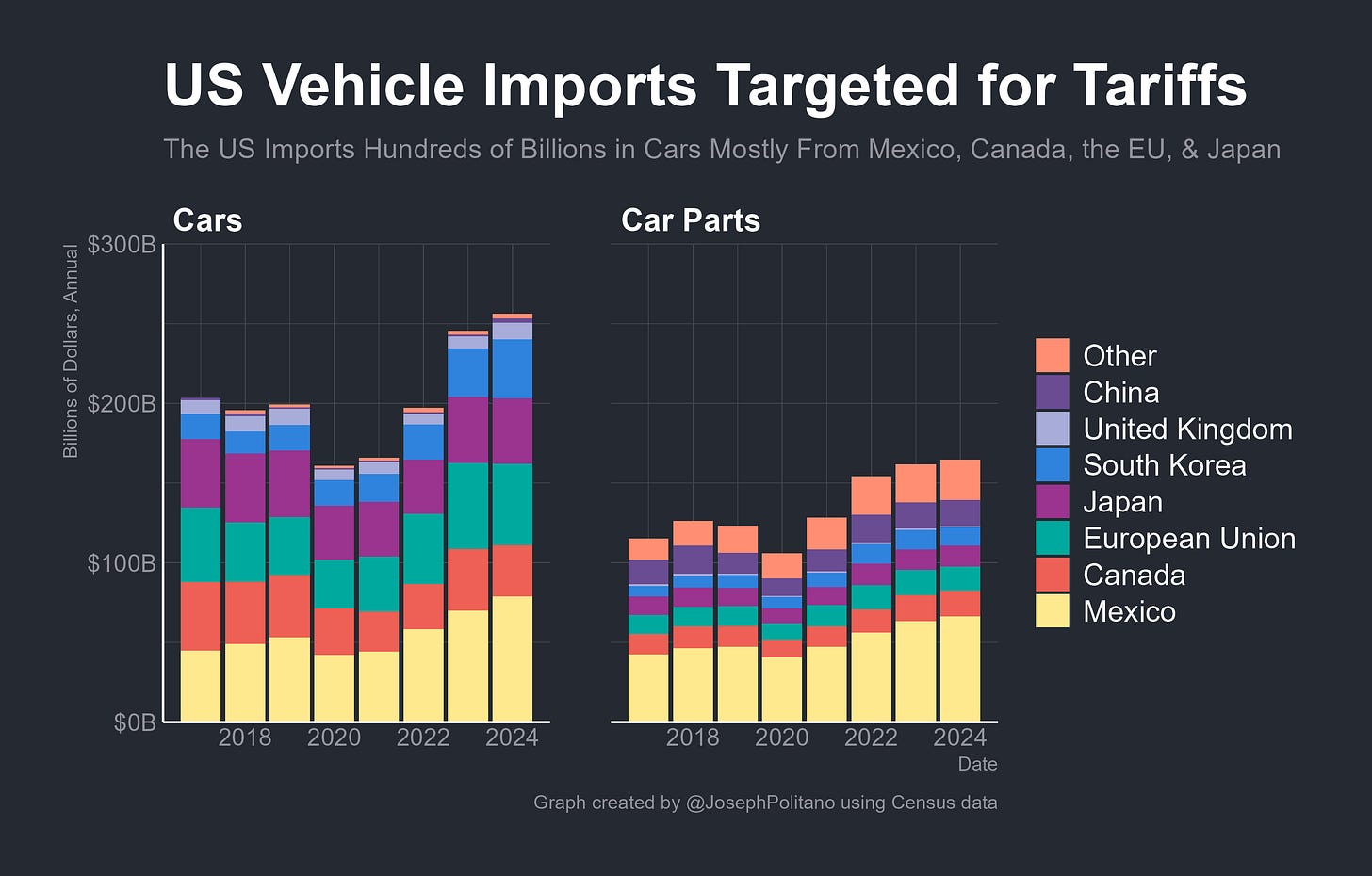

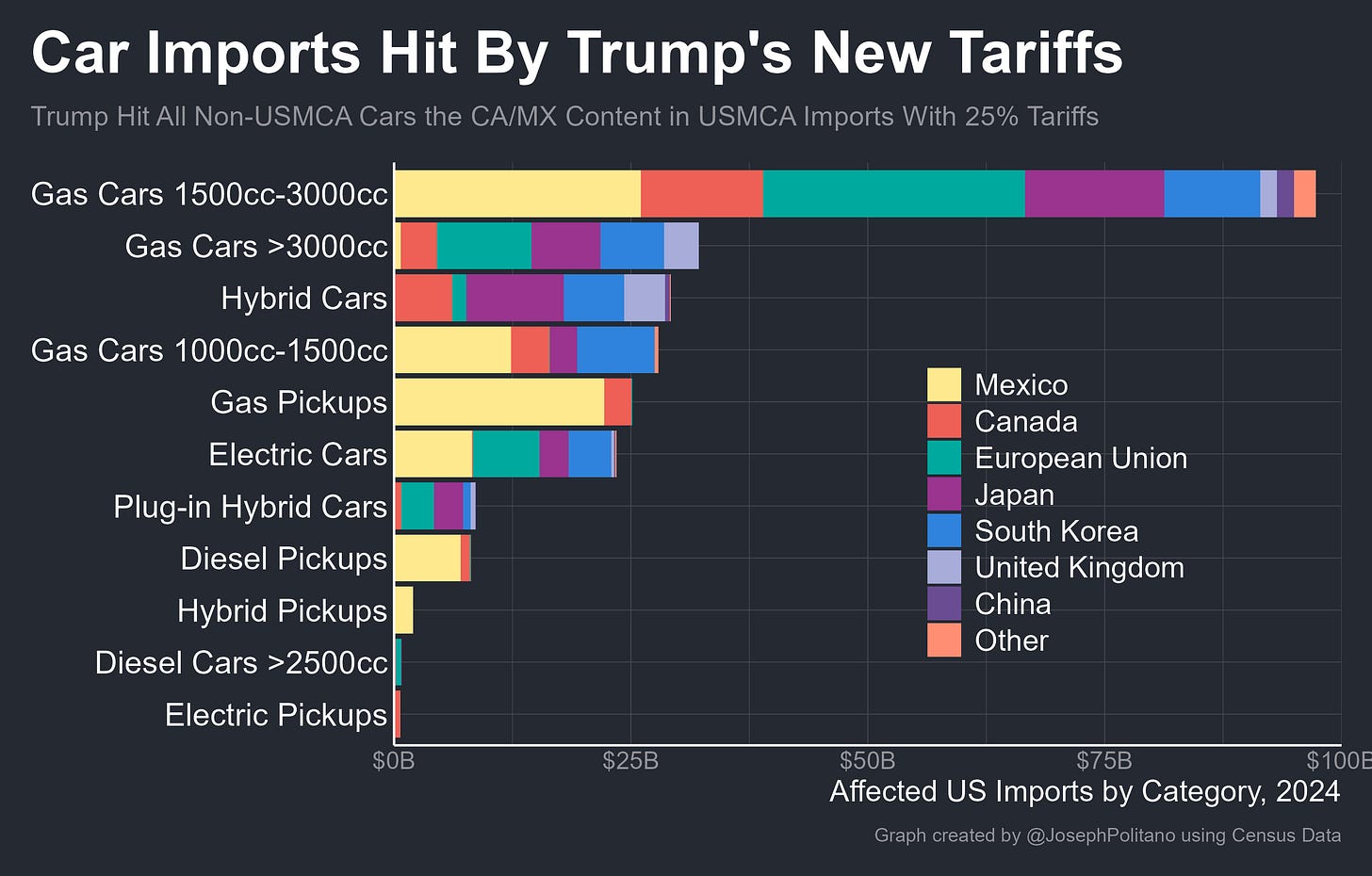

In any other administration, the announcement of 25% tariffs on cars & parts would be the single-largest economic story of the year—they currently hit more than $353B in US imports, having a larger economic effect than all of the tariffs implemented during Trump’s first term combined. These tariffs primarily affect imports from close American allies like the EU, Japan, & South Korea, who supply the majority of foreign-made cars to the United States. Yet the President won’t even spare the highly integrated North American supply chain, as tariffs currently apply to the non-US content in Mexican and Canadian-made vehicles.

Tariffs will also eventually be applied to the non-US content in Mexican/Canadian-made parts, which would increase the amount of imports affected by tariffs by another $68B when implemented. Plus, the Trump administration is looking to expand the trade war even further with tariffs on foreign-made heavy trucks and their parts, which could increase the amount of affected vehicle imports by roughly another $20B.

All of this was implemented in the maximally chaotic Trumpian way—only days before the tariffs on car parts were set to go into effect, the White House announced that they would not “stack” with other existing tariffs on steel, aluminum, China, or non-USMCA-compliant Canadian/Mexican goods. A steel car part from China could have faced additional tariffs of 70% (25% for being a car part, 25% for its steel content, and 20% for being from China) above the high preexisting tariffs from Trump’s first-term trade war, but now instead faces “only” a 25% increase.

At the same time, the administration announced a complex system of rebates for domestic carmakers to partially offset the tariffs on their input parts in the near term. Any company that manufactures vehicles in the US can claim a rebate worth up to 3.75% of the price of their cars, which is enough to offset the tariffs on components worth up to 15% of the car’s value. Next year, that rebate shrinks to 2.5%, and afterwards it totally disappears.

Finally, even though both executive orders mentioned that the US would eventually be applying tariffs to the Mexican & Canadian content of USMCA-compliant parts, no process to assess those tariffs or schedule for their implementation has been announced. A fact sheet from the White House seems to suggest the new rebate is designed to offset the cost of tariffs on non-USMCA-compliant auto parts, implying the tariffs on USMCA-compliant parts won’t be implemented for at least two years—but this is no hard guarantee and the administration could easily change their minds again at any point. The USMCA is set to be renegotiated next year anyway, so tariffs on parts from America’s neighbors could still change substantially.

Then, Trump signed his first preliminary trade “deal” with the United Kingdom, where the largest US tariff reduction came from a new tariff-rate-quota system for British vehicles. All UK cars still face tariffs, but the first 100k exports face only a 10% tariff while any additional exports face the full 25%. This is not a consequential change to vehicle tariffs, as the UK only makes up roughly 4% of American car imports and is heavily concentrated in the luxury segment, but this “deal” will likely serve as a model for negotiations with larger trade partners.

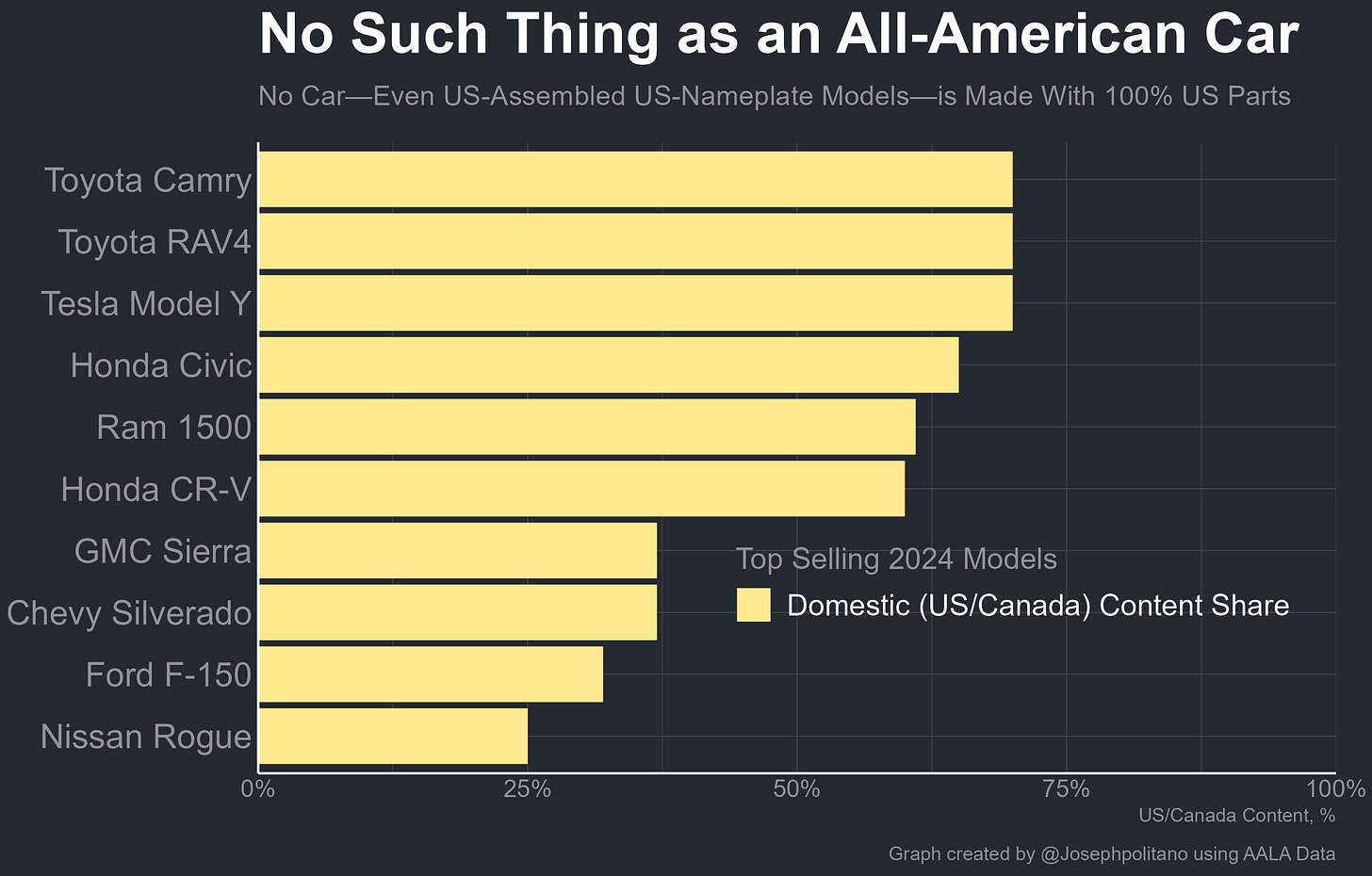

Still, roughly half of the cars bought in America are foreign-assembled vehicles that will be directly affected by the tariffs, and it’ll be impossible for even US-made vehicles to completely avoid being impacted. That’s purely because there is no such thing as an “all-American” car—among the most popular models last year, none are more than 70% American when you account for the embedded value of foreign parts, and most contain even more imported components than that. Bestselling iconic vehicles like the Ford F-150 are less than a third American. Even this data overstates it—the American and Canadian car industries are so tightly intertwined that the US government doesn’t even try to parse their contributions apart, yet Trump still plows forward with tariffs against his northern neighbor.

That disruption will also hit at a particularly difficult time for the US auto industry. Prices for new and used vehicles are still stubbornly high years after the inflation surge of 2021. Auto loan delinquencies continue rising as consumers struggle to keep up with payments amidst the high cost of living. Domestic vehicle production remains weak, and automakers have shed more than twenty thousand jobs over the last year. People who could afford to were already rushing to buy up cars before tariffs went into effect, reducing dealerships’ existing inventory. Plus, American industry has fallen technologically behind the rapidly growing Chinese EV makers from whom it already enjoys steep trade protection, and Trump is set on dismantling the Inflation Reduction Act policies that were at least attempting to catch them up. Companies like Ford and Subaru are already being forced to withdraw their annual guidance and hike prices for their foreign-made models. At this difficult moment, tariffs will make things worse by adding $6400 to the average price of a new car, increasing the costs of assembling vehicles in the US, and encouraging technological complacency among domestic automakers.