America's Fractured Housing Market

The Pandemic Broke America's Housing Market in More Ways Than One

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 14,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Paid annual subscriptions are 20% off to celebrate the newsletter’s launch! Other discounts are available for students, teachers, government employees, journalists, and any groups of four or more.

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

In early 2020, COVID-19 represented arguably the biggest negative shock to the housing market since 2008. With unemployment rising to 14%, millions of people being forced to move back in with friends or family, and a large share of homeowners becoming at risk of foreclosure, the outlook for the housing market appeared grim.

Policymakers, though, are famously good at fighting the last war—remembering how bad the 2008 crisis was, they pulled out all the stops this time. The Federal Reserve started buying billions in Mortgage-Backed Securities, the federal government spun up a mortgage forbearance program for homeowners, cities and states implemented broad eviction moratoriums, and large amounts of money were disbursed in the form of unemployment benefits and stimulus checks to help workers make rent

By 2021, COVID-19 represented arguably the biggest positive shock to the housing market since 2008—making the initial panic about a possible housing market collapse seem almost ridiculous in retrospect. The feared surge in evictions and foreclosures never came to pass. Prices started skyrocketing as America’s preexisting acute housing shortage mixed with cash-flush buyers who suddenly desired much more space for more home-bound lifestyles. A working paper by John Mondragon and Johannes Wieland attributed half of the 30% increase in housing prices from the end of 2019 to the end of 2021 to the pandemic-driven shift to remote work.

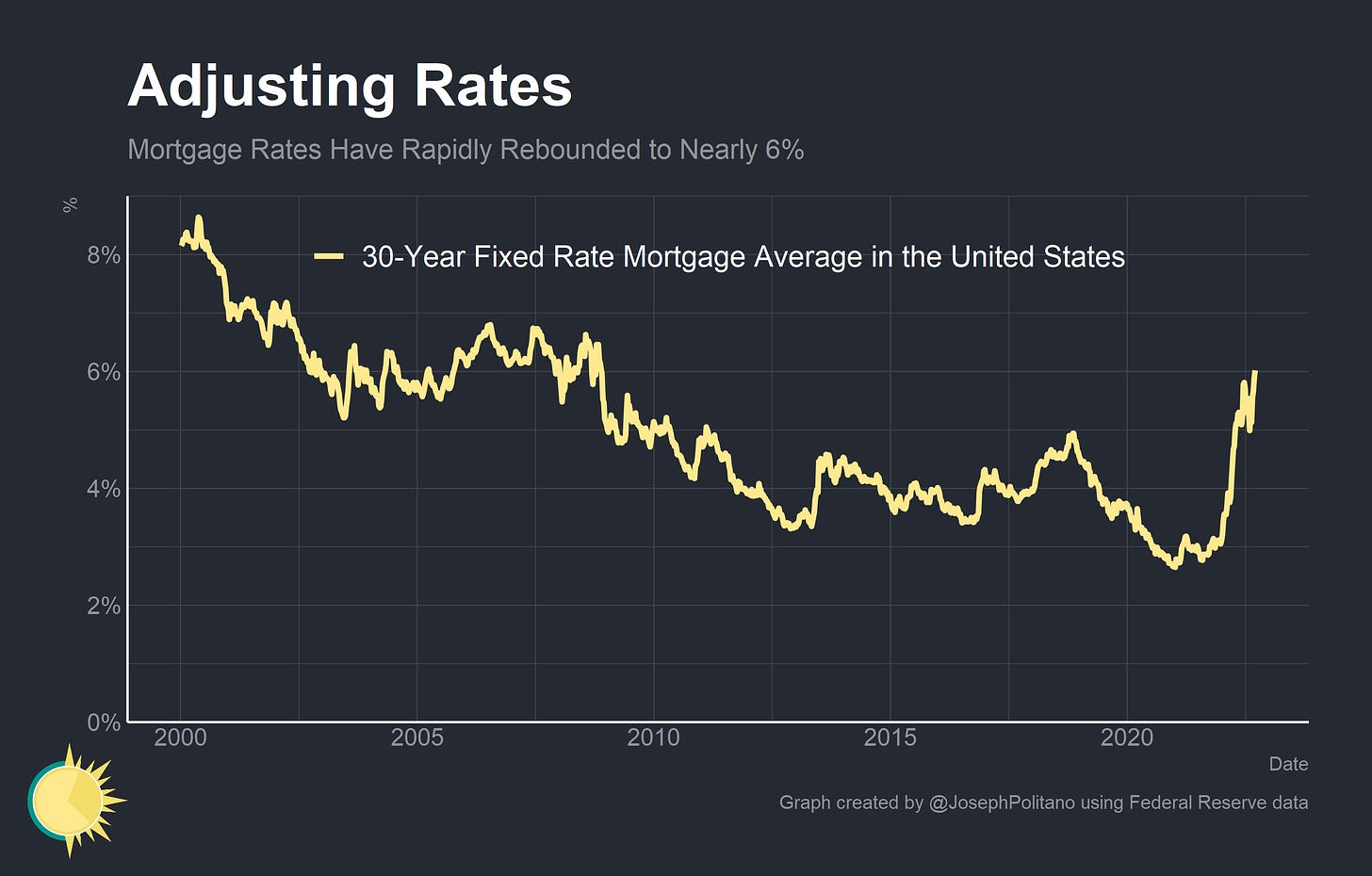

Today, the narrative has once again shifted. The Federal Reserve is focused on fighting inflation and is raising interest rates rapidly. Rising interest rates, accentuated by the inverted yield curve, are driving mortgage rates higher—as of September 20th, the daily 30-year fixed mortgage rate average is nearly 6.5%, higher than at any point since 2006. That’s pulled single-family housing starts down 20% from their pandemic highs and is driving worries about possible home price declines. Over the last few months, Zillow’s Home Value Index has stalled for the first time since the early pandemic.

However, the pandemic hasn’t just pushed around the housing market in aggregate. Despite the useful phraseology, it’s an oversimplification to say America has a housing market—rather, the US has thousands of loosely interconnected local housing markets that can be further subdivided by price, amenities, unit type, and more. The pandemic has done more than just change the US housing market—it has completely fractured it along a number of different, important dimensions.

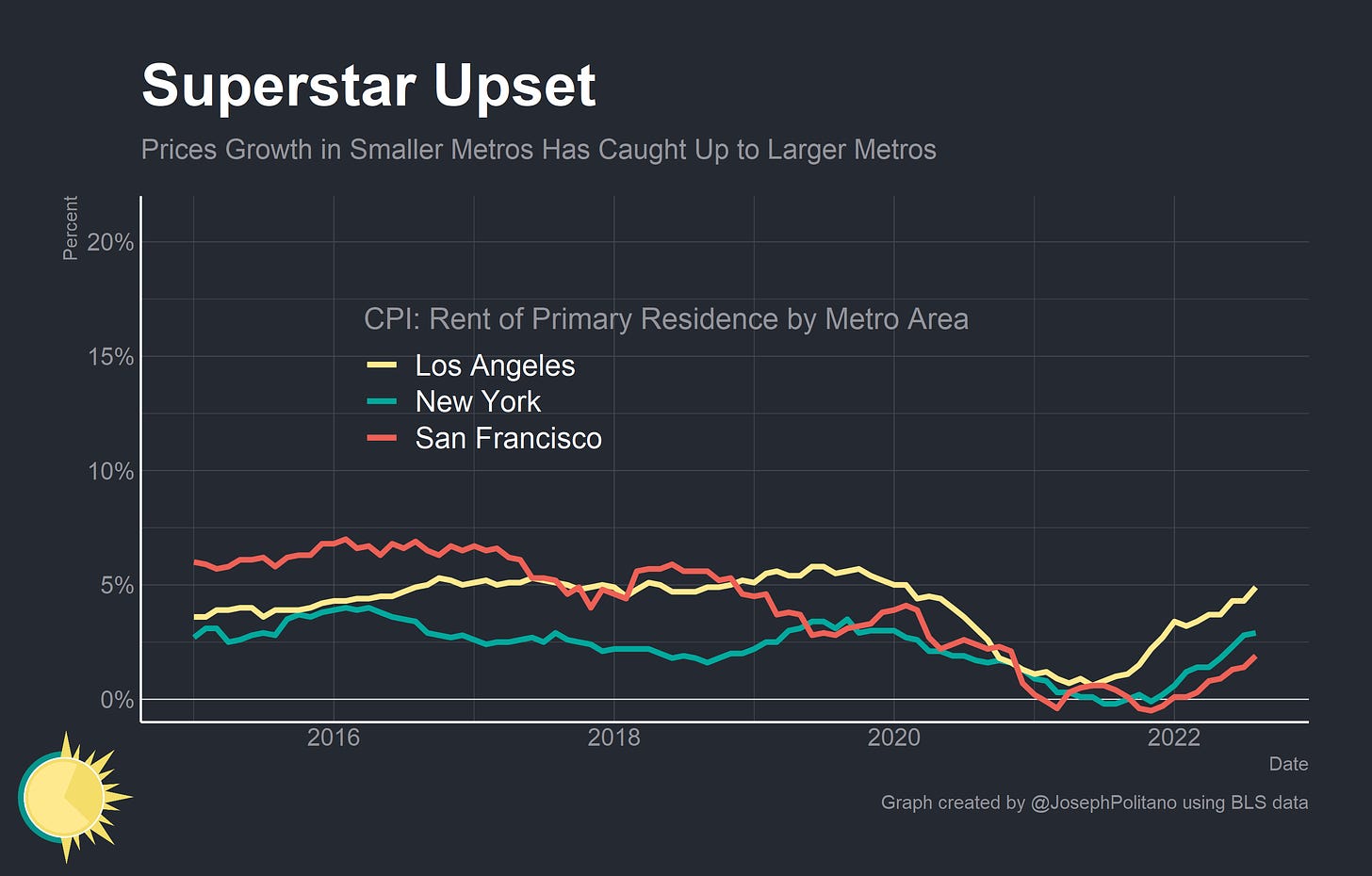

Blowing a 3-1 Lead

Before the pandemic, a lot of ink was spilled about the rise of America’s superstar cities. The country’s largest megalopolises—New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and to a lesser extent Boston, Seattle, etc—were blossoming centers for a number of high-wage jobs and industries. However, basically all of these superstar cities have systemically underbuilt housing for decades thanks to a combination of preexisting legal/bureaucratic biases against construction, concerted political efforts by local homeowners, and the housing collapse that occurred in 2008. As a result these major cities metaphorically hogged a large share of the nation’s economic opportunity—and made the price of admission sky-high housing prices. Rents in America’s largest cities regularly outpaced inflation by a factor of two and grew significantly faster than in the smaller, relatively cheaper cities.

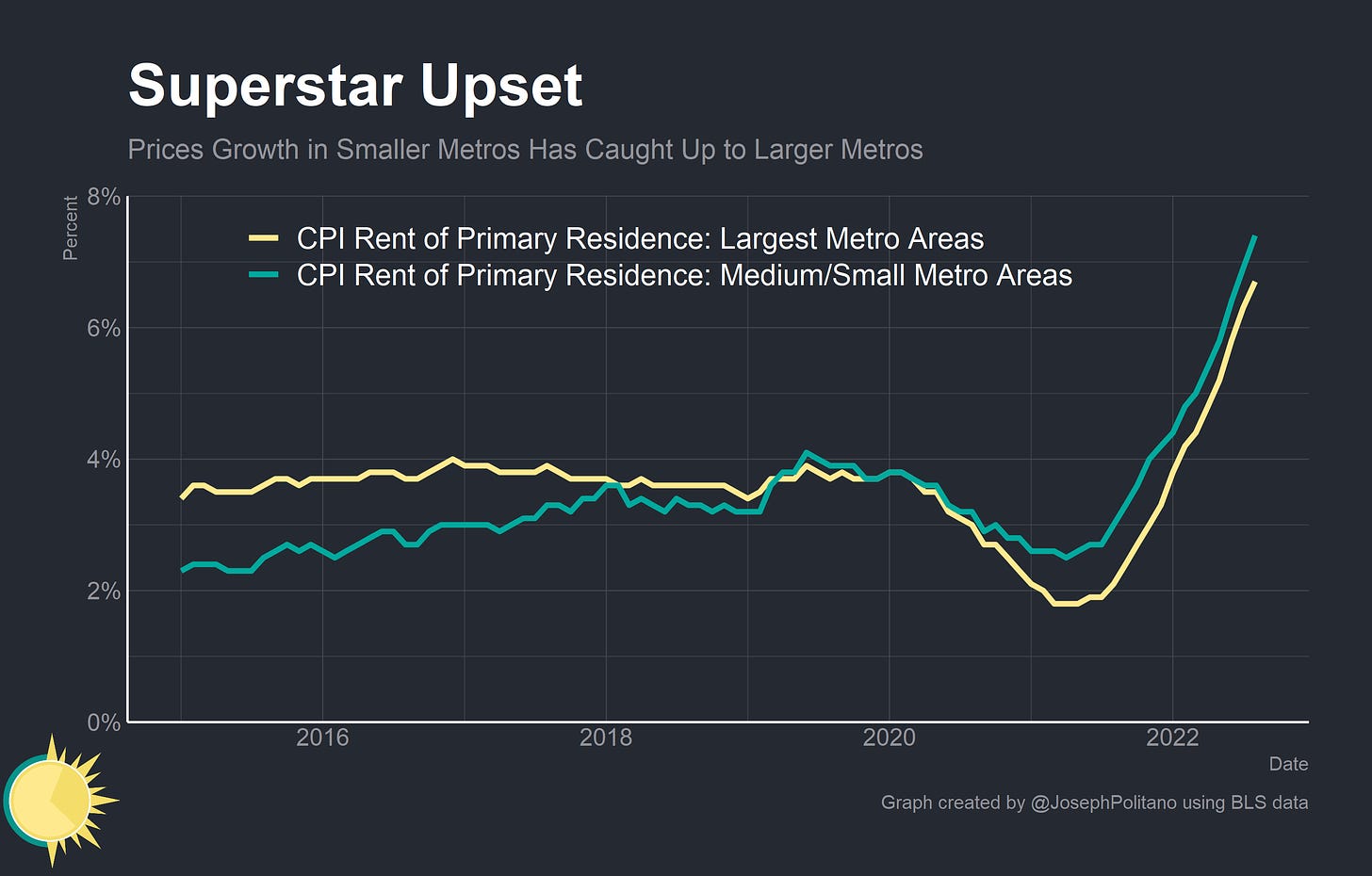

That was the first big housing market fracture to emerge relatively early in the pandemic—with the rapid increase in work from home and the drying up of demand for in-person service-sector labor in many large cities, plenty of workers decided to leave the superstar cities for greener (or at least cheaper) pastures. Rent growth skyrocketed in Phoenix, Atlanta, Miami, and other small metros in the South and Midwest that saw large population influxes. Redfin, a national real estate brokerage, estimates that their users’ inflow to Phoenix increased 50% from early 2019 to early 2021—and another 15% since then.

Rent growth in the superstar cities subsequently became lackluster—temporarily dipping below zero on a year-over-year basis in both New York and San Francisco. It has picked back up since then—especially with the global surge in inflation—but the pandemic has clearly left a semi-permanent mark on housing demand in many of these metro areas.

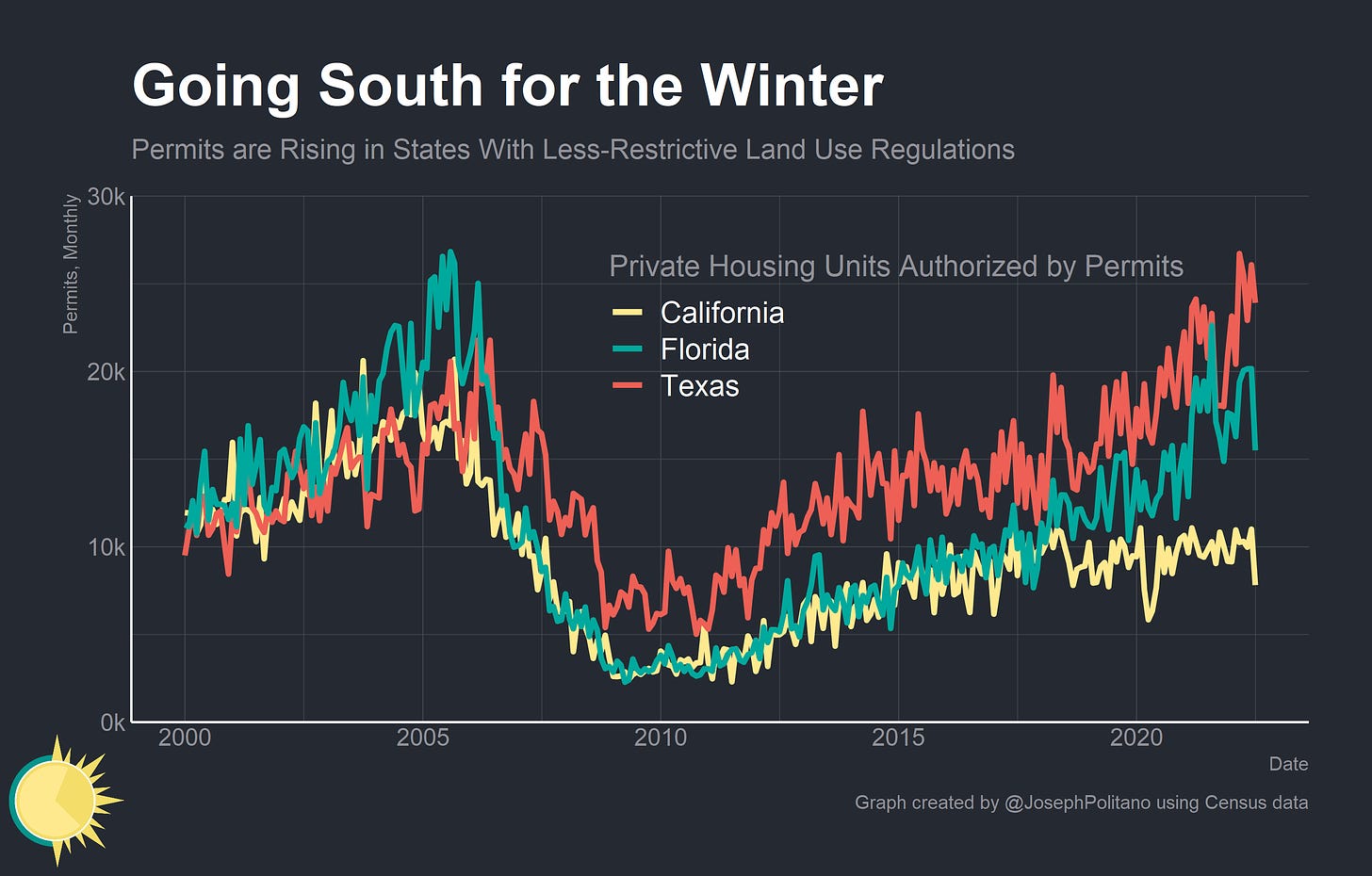

The interesting result of this pandemic-induced migration shock may have been a rise in overall construction levels. Texas and Florida have much less restrictive construction, land use, and zoning laws than California or New York—so an increase in the numbers of movers into Texas or Florida should mean more homes being built. Just to give you an idea of how large the discrepancy is—in 2021 Texas permitted double the number of units as California despite the latter having 10 million more people and nearly $20,000 more in GDP per capita.

The two lingering questions regarding this fracture in America’s housing market are if the superstar trend returns and if we get some new superstars. The core draw of the superstar cities was that it became necessary (and extremely lucrative) for companies within similar industries to heavily concentrate within select city centers—tech in San Francisco, finance in New York, etc—and that helped bootstrap those cities’ employment and wage growth in services running the gamut from delivery to hospital work. How much do geographic industry concentrations matter in an era when so many people can work from home? Obviously, not everyone in San Francisco is a tech worker (far from it), geographic concentrations still matter tremendously for in-person jobs like healthcare/transportation, and plenty of people pay a premium to live in cities for the better food, entertainment, education, and other amenities—but it remains to be seen whether the iron grip that superstar cities had over economic growth in the 2010s will survive.

Who gets to be a superstar city isn’t set in stone, either. Chicago was a center of opportunity across long periods of American economic history—but it didn’t benefit from the superstar city phenomenon much in the 2010s. Population growth in Atlanta, Austin, Phoenix, Dallas, Houston, Las Vegas, and others may have been partially accelerated because those cities represented outlet valves for those turned away by rising prices in NYC/DC/LA/SF, but that doesn’t mean those places can’t become superstars of their own. Raleigh and the research triangle have achieved one such strong agglomeration network—and North Carolina now permits nearly as many housing units as California. Tech companies are increasingly moving into Austin, Houston, Dallas, Miami, and other cities—perhaps one or more of those inherits the kind of compounding growth that propelled the DC area forward over the last couple of decades. So the superstar trend could stick around—with some new additions to the roster.

The Broken Supply Chain

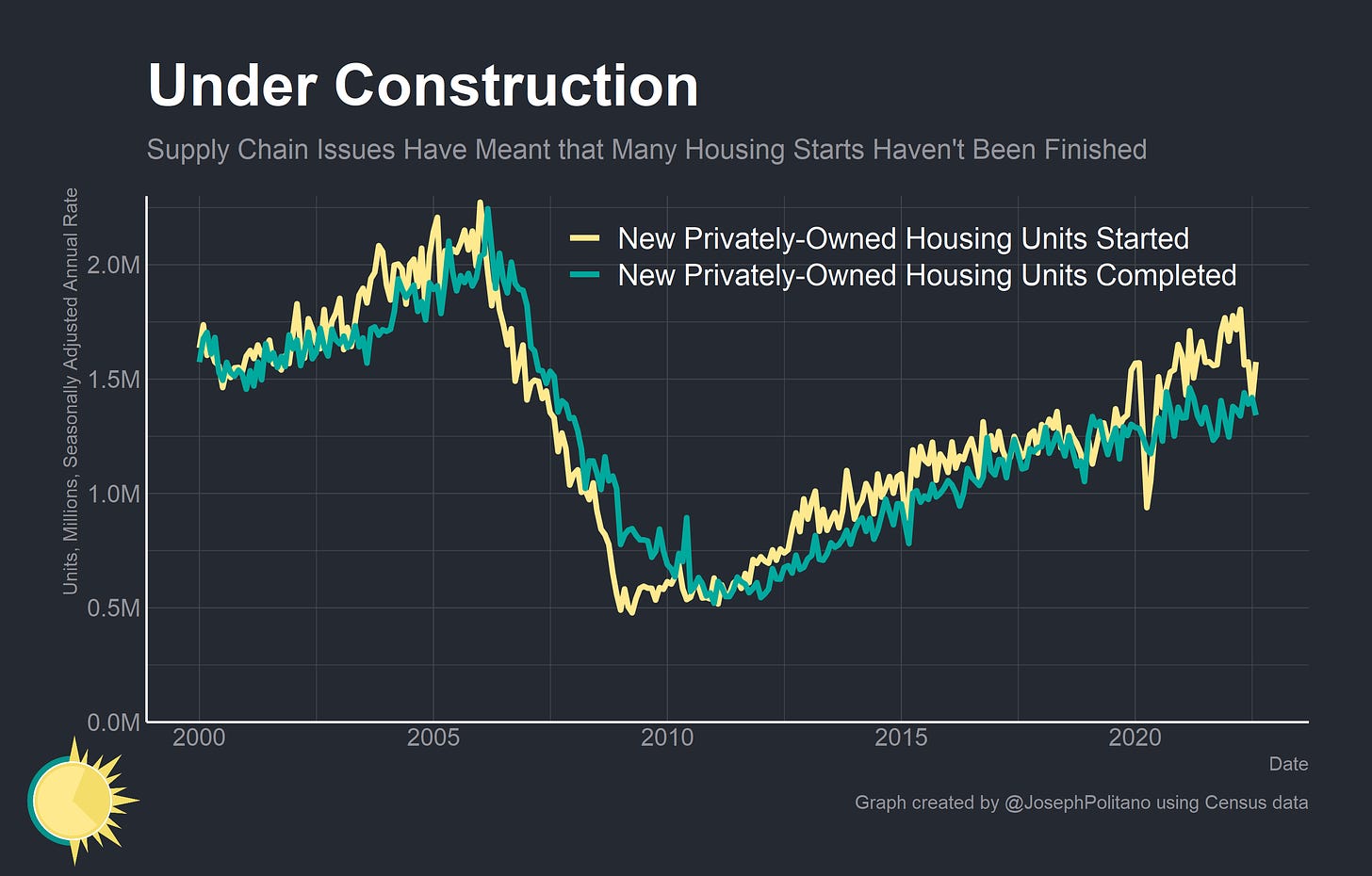

America’s housing supply chains also fractured during the pandemic—something I’ve written a bit about before. Rising mortgage rates may have had the semi-desired effect of cooling housing starts and permits, but housing completions remain stubbornly unmoved from their early pandemic levels. How the housing supply chain shakes out will have critically important effects on inflation and the US macroeconomic outlook.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.