America's Homebuilding Boom (That Isn't)

America is Building More Than it has in a Decade. It's Nowhere Near Enough.

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 4,600 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

In the years before and after the 2008 recession, American homebuilding completely collapsed. The financial crisis caused housing starts to plummet, and a weak labor market couldn’t support a recovery in rents until 2011. By 2015, though, the problem swapped: weak construction levels couldn’t support a recovery in the labor market. Real rents began climbing rapidly and consistently—something that hadn’t happened before in modern American history.

Today, new housing starts are higher than at any point since early 2006—but it’s nowhere near enough to keep up with population growth, let alone make up for the decade of lost construction. The pandemic has driven increased demand for housing as living patterns shift and incomes improve, but construction is falling behind. Supply chain issues are increasing building costs, keeping housing completions low, and preventing many projects from even breaking ground. Underconstruction has pushed vacancy rates to the lowest levels in nearly 40 years, indicating just how severe the housing shortage has gotten.

There may be a construction boom, but it’s a false boom—one dwarfed by the size of the demand it is trying to satiate. Across America (but especially in major cities), it still remains incredibly difficult or outright illegal to build new housing of any type. More and more Americans are moving into lower cost cities in the South and Southeast, but even these places are failing to keep up. The US will still need millions more homes before demand is even close to satiated—and today’s construction boom needs to be placed in the proper context of an acute housing shortage.

If you Build it…

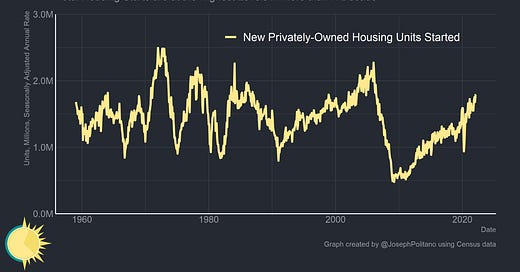

After steadily climbing out of the post-2008 hole, new housing starts have been on a serious uptick since the start of the pandemic. As it stands, starts are about 12% higher than they were just before COVID hit, a level of homebuilding not seen since the early 2000s. Aggregate homebuilding is being carried by record construction levels in the big metro areas of Texas (Dallas, Houston, and Austin) and strong building throughout other cities in the South (like Orlando and Phoenix).

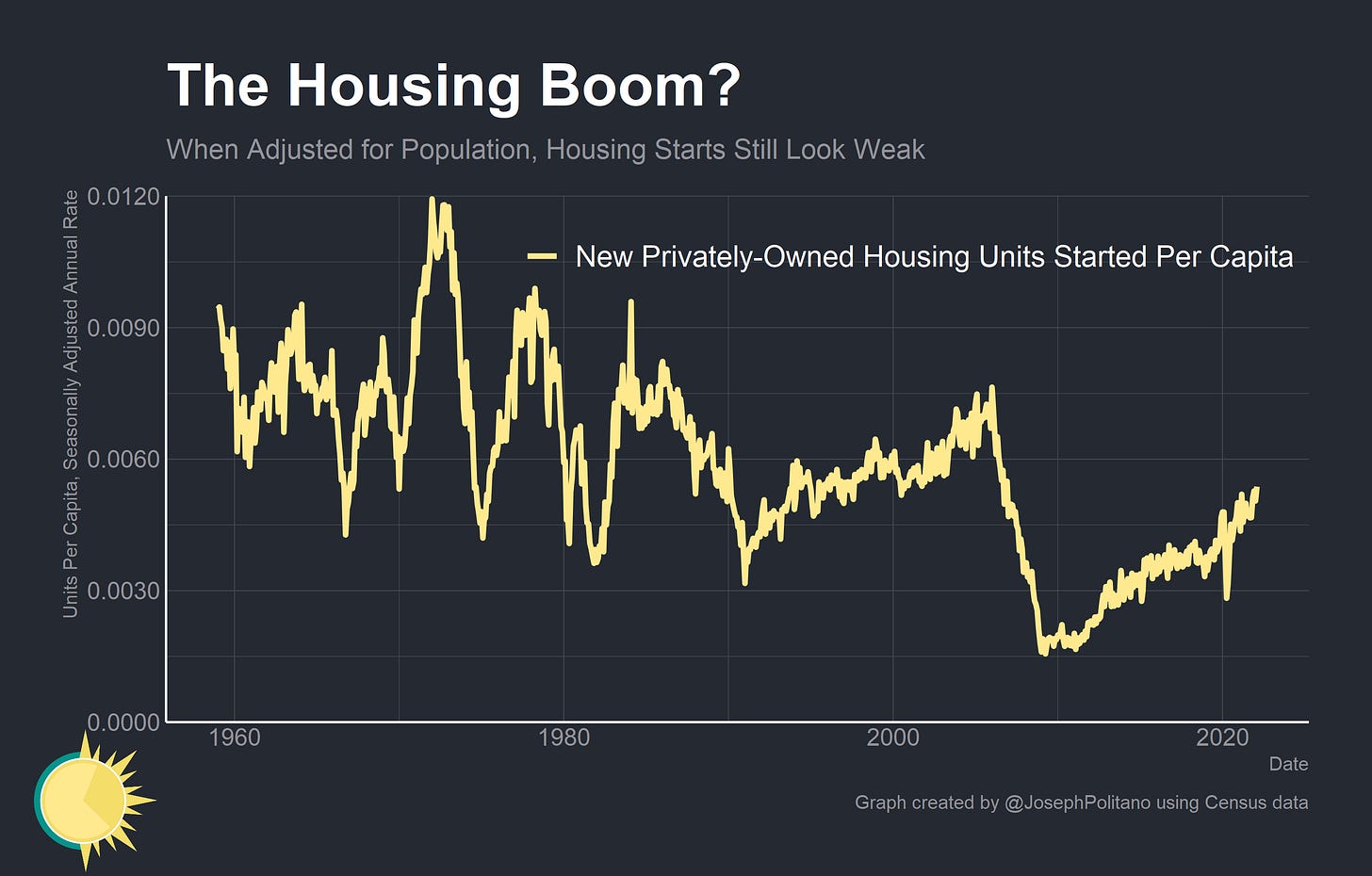

However, the construction surge has still left total homebuilding at historically weak levels. Relative to America’s still-growing population, homebuilding is hovering near pre-2008 lows. That’s despite a deficit of millions of units that need to be built and a housing stock that is increasingly outdated. Construction would have to at least match the boom periods of yesteryear to make a dent in real rental costs.

Growth in the housing stock—which takes into account both new construction and new destruction—has also been extremely low compared to the pre-Great Recession years. Granted, America’s net population growth is lower than it was in the early 200s (~0.5% in 2019 versus ~1.1% in 2001) but a wide variety of non-population factors have made housing demand extremely strong.

Household formation is a critical concept in determining housing demand, but it can be extremely difficult to accurately track. The general theory is simple enough: people tend to live in the same house as their parents until they reach a certain age and move out to live alone, with a significant other, or with roommates. That moving out represents household formation (which can also occur with divorces, old age, and other life events, but growing up is generally the biggest contributor and main focus). The problem is that household formation affects—and is affected by—price. In general, people tend to move out when they grow up, and an increase in the number of people aging into adulthood can push up housing demand. But if rent is too expensive than these young adults are more likely to stay with their parents—which is exactly what has happened in America over the last 20 years. That keeps household formation numbers low despite high housing demand growth.

A few reinforcing factors relating to household formation have pushed housing demand higher despite weak population growth. The first is a general increase in housing’s relative importance to consumers. People (especially during the pandemic) are spending more time at home—working from home, consuming media at home, and socializing at home. That makes the average person more willing to spend on floorspace. The second factor is a delay in marriages—by 2019 the median age at first marriage had risen to nearly 30 for men and 28 for women, a jump of 4 years since the 1990s. More time unmarried means more demand for separate bedrooms and separate units. The final factor is a general trend towards preferences for living alone. The data for this is admittedly less compelling, but falls into the general multi-decade trend of Americans living more socially isolated and atomized lives. A 2015 survey found that 58% of millennial renters with roommates would prefer to live alone. That preference, unsurprisingly, drives up housing demand. Mix that in with the massive number of millennials aging into their homebuying years and you have a picture that is extremely complicated but points to strong housing demand.

While assessing the impacts of household formation on the housing market can be exceptionally difficult, vacancy rates can help gauge the strength of demand without examining price. In any given month, a certain number of units will be in between tenants or otherwise vacant. The vacancy rate will usually tick down when demand outstrips supply and new tenants are constantly scrambling to fill available units—and right now the rental vacancy rate is at the lowest level since the early 1980s. In fact, the homeowner vacancy rate is at the lowest level ever. On the whole, the rise in housing construction must be put in context against the backdrop of possibly the most severe housing shortage in American history.

Will they Come?

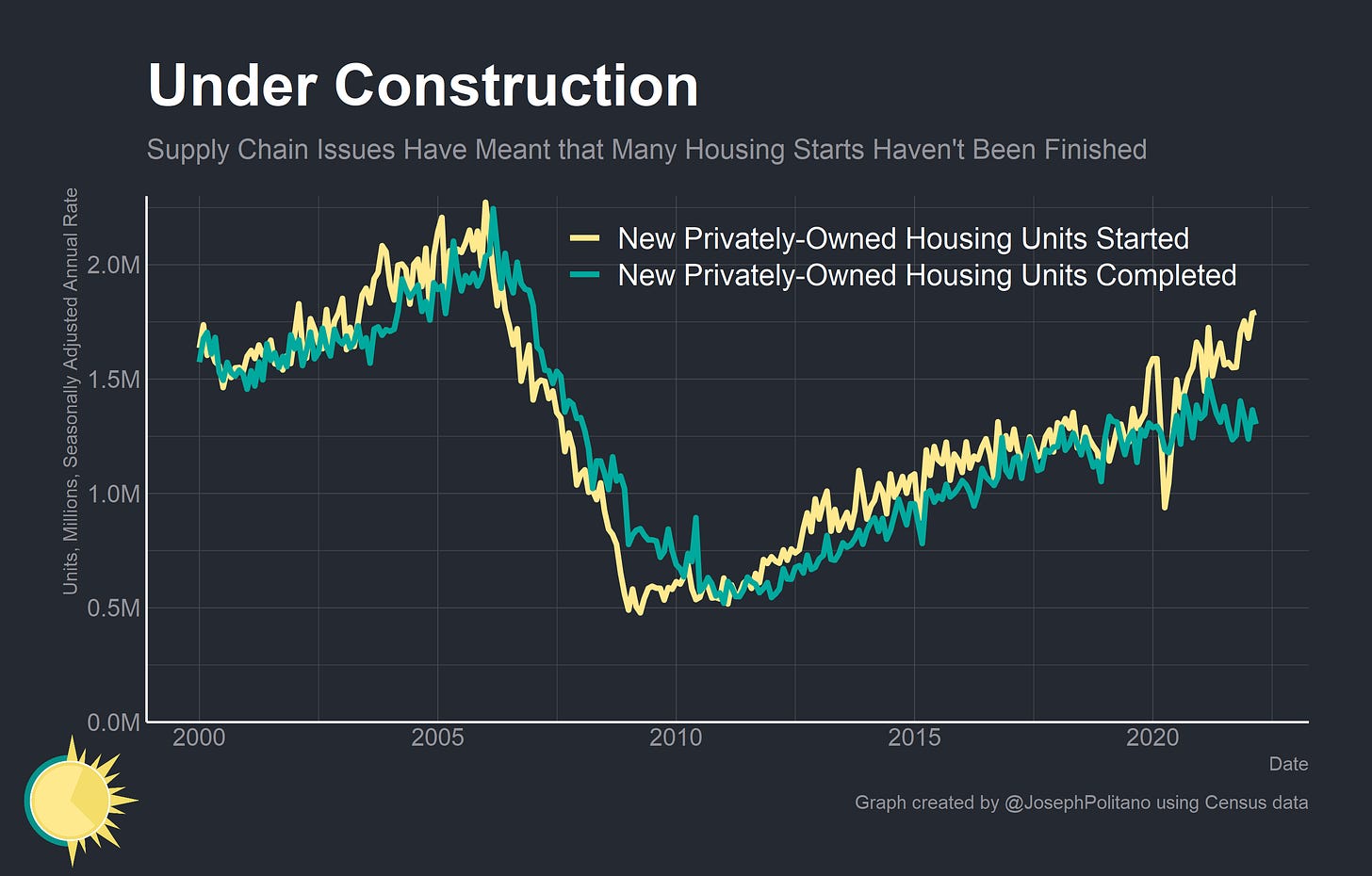

Supply chain issues ranging from commodity prices to labor shortages have also put a damper on housing production. Housing starts have jumped up over the last two years amidst strong demand and rising home prices—but completions have not kept up. Projects are taking longer to complete thanks to rolling shortages and production interruptions that have plagued the industry.

As a result, the number of housing units under construction has surged to record levels and shows little signs of slowing.

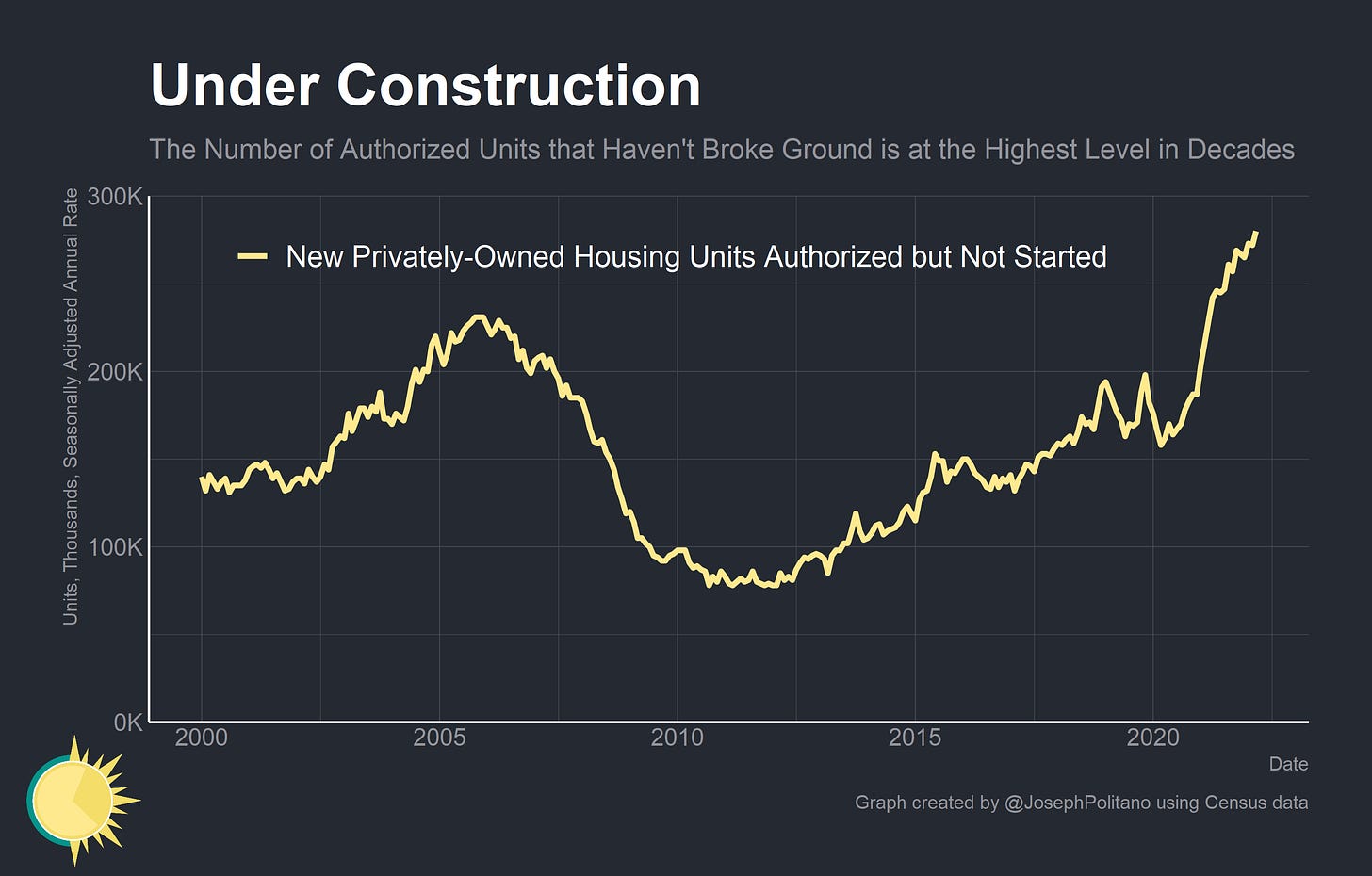

At the same time, the number of housing unit authorized but not started is also at a record high. The same supply issues that is are delaying construction are also making it difficult to even break ground. Builders often have a hard time quickly scaling up production—something that has been made all the worse by the pandemic—so extended construction times can manifest as delays to housing starts.

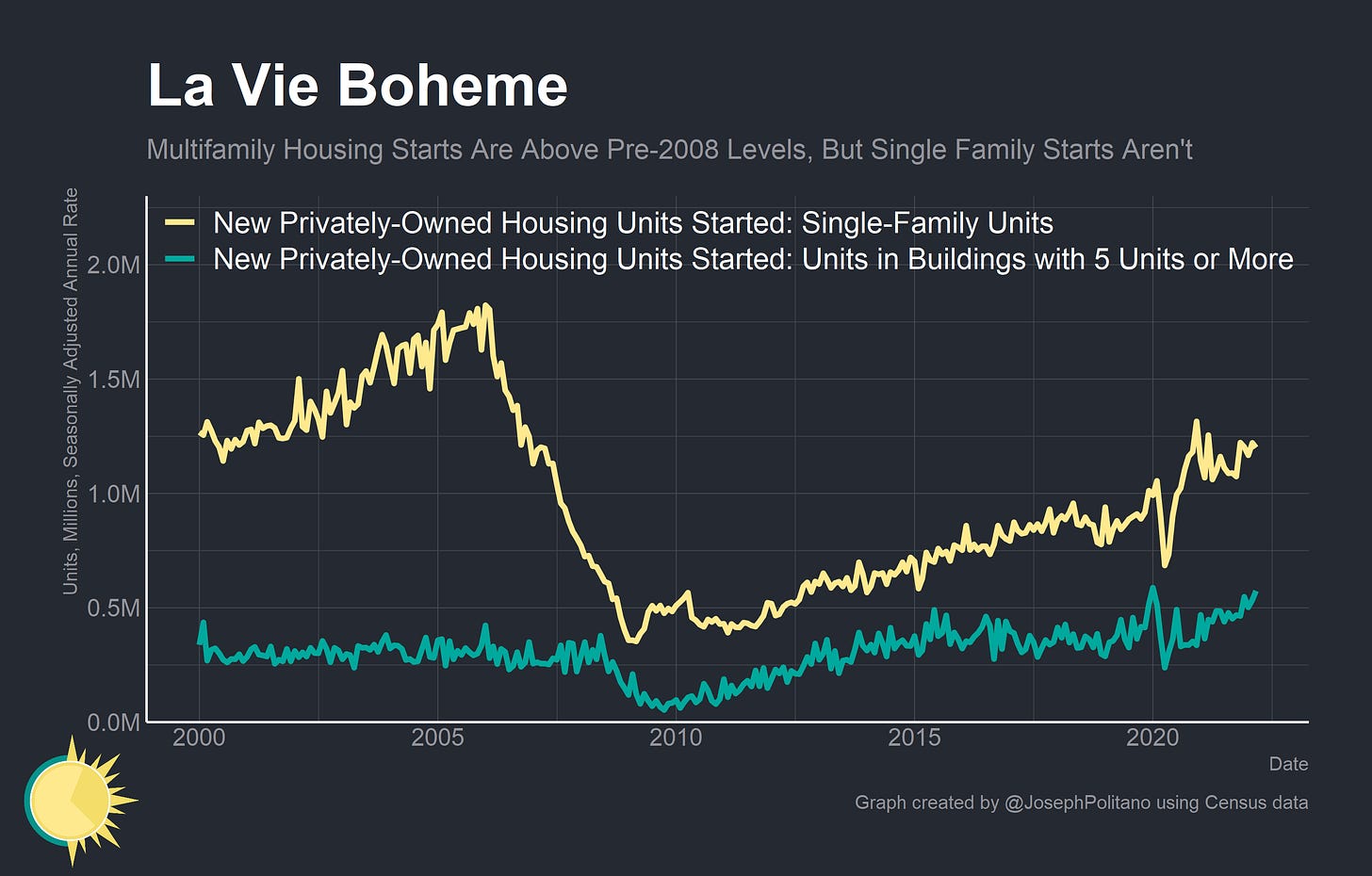

It’s also important to recognize that the type of housing construction has changed significantly. Right now, America is building more multifamily housing than it has in three decades. Post-2008, multifamily housing has composed a significantly larger share of total construction as household financing became tighter, young adults married later, and an increasing share of workers lived in the downtowns of major cities.

Multifamily construction basically recovered to pre-Great Recession levels by 2012, but single-family construction has never fully recovered—and to understand why, it is worth discussing the important shift in migration and construction patterns that has occurred over the last two decades. Before the Great Recession—as Kevin Erdmann explains in his book Shut Out—Americans were leaving the expensive “closed access” cities like New York and Los Angeles for the “contagion” cities like Phoenix and Tampa. Zoning and planning regulations had made housing construction illegal or extremely difficult in the “closed access” cities, so workers unable to afford the big city chose to buy newly-constructed single-family homes in the less-overregulated “contagion” cities. After the financial crisis these “contagion” cities were devastated, and outmigration from the “closed access” cities dramatically slowed due to the worsening labor market.

Now, we are in a third paradigm that started in the late 2010s but has been supercharged by telecommuting and the shifting economic geography caused by the pandemic. In the two years since COVID hit the US, workers have increasingly left the downtown areas of major cities for their suburbs and exurbs. At the same time, they have left expensive states altogether for cheaper ones. This is fairly revolutionary in its own right, but the knock-on effect of these moves could be even more important: workers are again moving from supply-constrained “closed access” cities to areas that choose to permit more construction. It is easier to build in the Dallas metropolitan area than the Los Angeles metropolitan area, so the movement of workers from LA to Dallas can generate an uptick in overall construction. A similar effect, though on a smaller scale, occurs between the downtowns and suburbs of many cities. As pandemic-era restrictions end, it will be critical to see to what degree remote work and its new migration paradigm persists.

Finally, it’s worth talking about construction costs. Single-family home construction costs are up 14% over the last year, though multi-family costs are only up 4%. That’s not actually great news for multi-family construction—the longer build times of larger housing projects means that it usually takes longer for shifts in input costs to show up in the data. Rest assured, the massive jumps in input costs like lumber are affecting construction costs for single-family and multi-family homes alike.

Conclusions

Residential construction may be at the highest levels in more than 15 years, but that headline number betrays a lot of weakness under the surface. Completions are still weak and many projects haven’t even broken ground. Vacancies are exceptionally low and construction costs are rising quickly. Many projects are located in second-best areas: banished from the most desirable cities, construction has to make a home elsewhere. Americans’ per-capita housing demand may be at the highest levels ever, and strong labor income growth is pushing up housing demand. No wonder home prices are up nearly 20% over the last year.

Rising mortgage rates will likely cool off home values in the same way lowering rates helped supercharged them: by changing discount rates and buyer’s ability to finance purchases. The monthly payment on an average new mortgage of an average home has shot up recently as borrowing rates rise—and it is possible that home prices will have to decline to compensate. But these kinds of contractionary monetary policy shocks actually temporarily raise rents by making homeownership less attainable as shown by Daniel Dias and João Duarte in one of my favorite new papers. So if home prices do drop (despite a strong labor market and the housing shortage), it may be cold comfort to millions of American renters.

This only looks like a homebuilding boom against nearly a decade of housing underproduction. Compared to the scale of the housing shortage, this construction boom isn’t nearly enough. So what should be done? Everything. It is almost impossible to understate how detrimental the housing shortage is to America’s economic well-being—a now-famous Hsieh and Moretti paper estimated that total US GDP was 14-36% lower due to the impact of housing supply restrictions in just a few major American metros. While the priority should be unblocking construction in these cities, the scale of the problem is so vast that nearly anything that can increase construction will be beneficial. The only way out is to keep building.

great post joey!

Nice post. Is there some way to quantify / chart the shortage?