Core Inflation is (Finally) Cooling

Tighter Monetary Policy is Now Slowing the Underlying Cyclical Components of Inflation

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 28,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

The last year has seen a massive shift in the drivers of overall US inflation from the food, energy, and core goods prices most affected by COVID, the supply-chain crisis, and the war in Ukraine to the core, cyclical services most affected by excess aggregate demand. Annual price increases peaked for core manufactured goods at 12.4% in February 2022, peaked for energy at 41.6% in June 2022, and peaked for food at 11.4% in August 2022 even as core services price growth continued rising to 40-year highs. Now, however, it is clear that annual core services price increases have also peaked—at 7.3% in February.

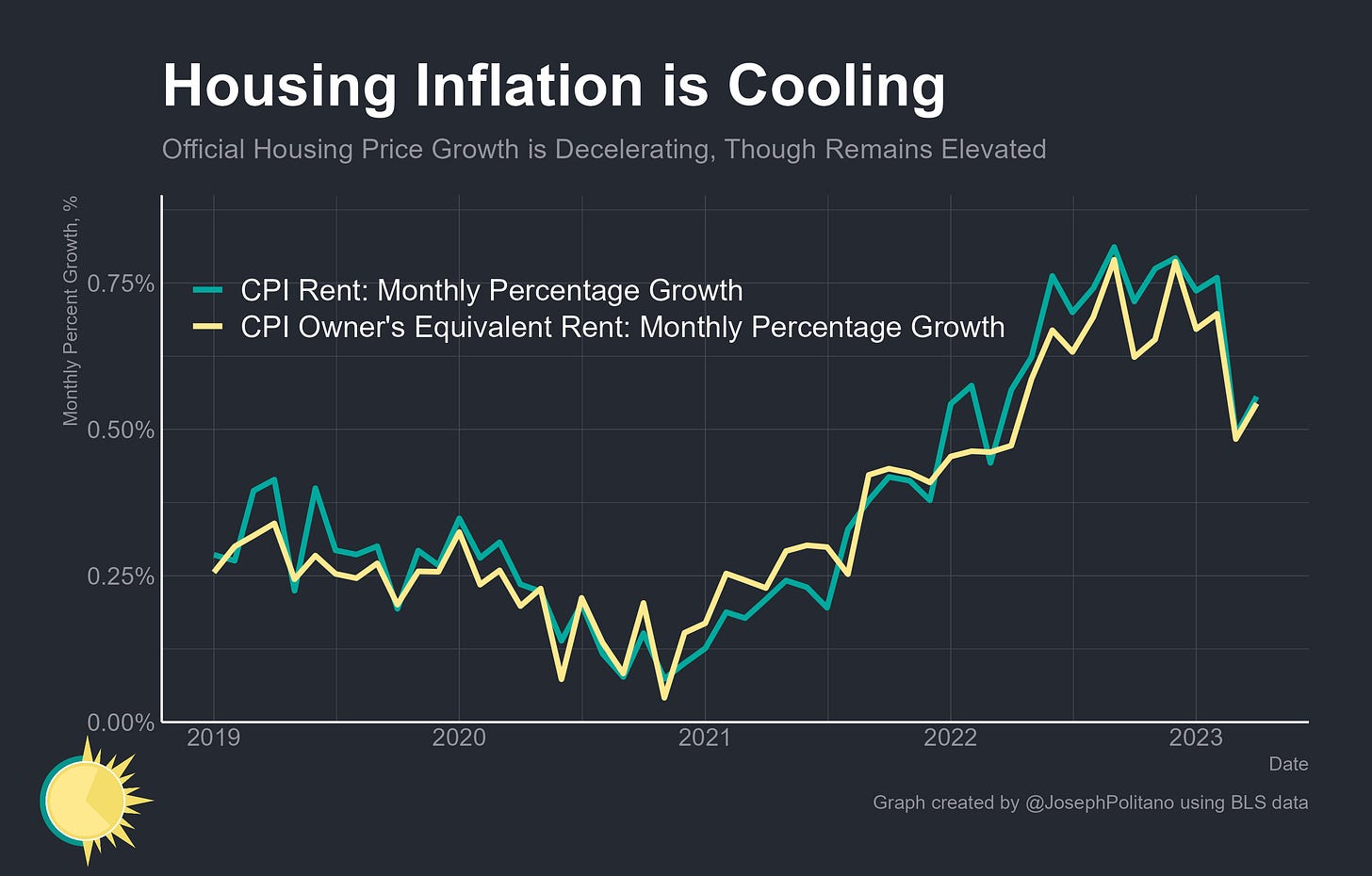

Indeed, month-on-month growth in core services price slowed to 0.36% in April, the lowest number since September 2021. Housing price increases in particular have come in well below their 2022 highs for two months in a row, and the services less rent price index has held near normal pre-pandemic growth rates for 3 months. Month-on-month food price inflation has also dissipated, with energy prices only contributing small positive amounts.

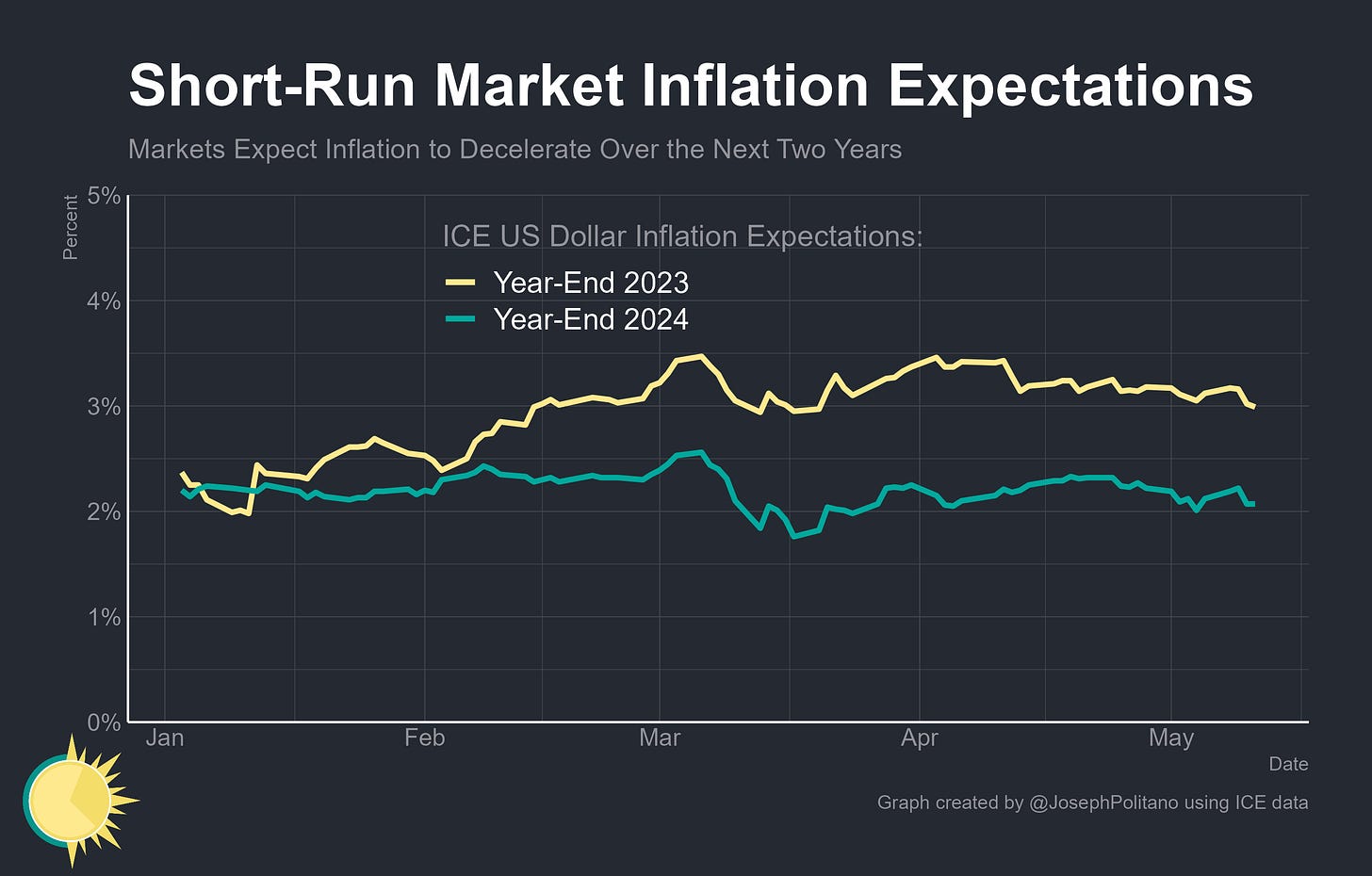

That’s driven year-on-year CPI inflation to the lowest level since May 2021—and has technically brought “core” CPI inflation excluding food and energy to the lowest level since December 2021 (though core inflation has been hovering in the 5.5-5.7% range since the start of the year). Services price inflation has fallen to 6.8%, with the shelter component peaking recently and decelerating slightly and the non-shelter components falling to the lowest level since early 2022. That means we're seeing progress towards stabilizing the core services ex-housing price increases that the Fed views as critical to underlying inflation, and that labor cost pressures are fading as the economy cools. Market-based inflation expectations now see CPI inflation ending 2023 at around 3% and falling to a more normal 2% in 2024—a sign that monetary policy is slowly bringing inflation back into line.

Breaking Down the Data

Rent prices are perhaps the most cyclical part of underlying inflation, being tightly related to employment, wage, and income growth on a one-year lag. Throughout 2022 housing price increases have been a massive positive contributor to headline inflation, rising at the fastest pace in 40 years as the economy overheated. Now, however, rent inflation is finally decelerating—rising at a pace substantially lower than the late-2022 average for two consecutive months.

We are therefore almost certainly past peak rent inflation now—price increases for new leases began rapidly decelerating this time last year, and we should begin seeing similar decelerations in official rent prices from this point forward. The housing categories of CPI will likely remain elevated for a while—the current lower pace still represents growth in excess of 6% per year, and underlying wage and income growth has yet to return to normal levels—but the worst is behind us.

Outside of housing, the decline in core services inflation has been more sustained and sharp. Annual increases in services prices excluding shelter have fallen from a peak in excess of 8% to just over 5% now. Not all of this represents deceleration in cyclical inflation—transportation services, which are driven largely by fuel and vehicle costs, and medical care services, which tend to be somewhat acyclical and idiosyncratic, have driven some of the decline—but it still indicates progress in reducing the stickier components of inflation.

There was, however, a significant bump in core inflation this month from a resurgence in used vehicle prices. After rising more than 50% throughout 2020 and 2021, official used car prices declined throughout 2022 and early 2023 as the semiconductor shortage eased and supply-chains improved. Wholesale prices, however, had been rising for several months consecutively as stronger demand and another shortfall in production hit the car market—and we just saw those wholesale price increases pass through to official inflation as the CPI used vehicles index bounced up 4.4% last month. This likely isn't the end for used car inflation either, as much of the wholesale price rebound hasn't passed through to retail prices and official data yet.

Another way of looking at the shift in underlying inflation is to take the core personal consumption expenditures price index (the Fed's preferred measure of inflation), analyze the underlying trend inflation level, and decompose the excess inflation (that which is above the Fed's 2% target) into its components. That's what Martín Almuzara, Babur Kocaoglou, and Argia Sbordone at the New York Fed have done in their multivariate core trend inflation analysis. In that, they find the contribution to excess inflation from goods and services ex-housing prices have been decreasing for more than a year now as the contribution from housing has grown—though all three are still pushing underlying inflation above trend.

Looking Ahead

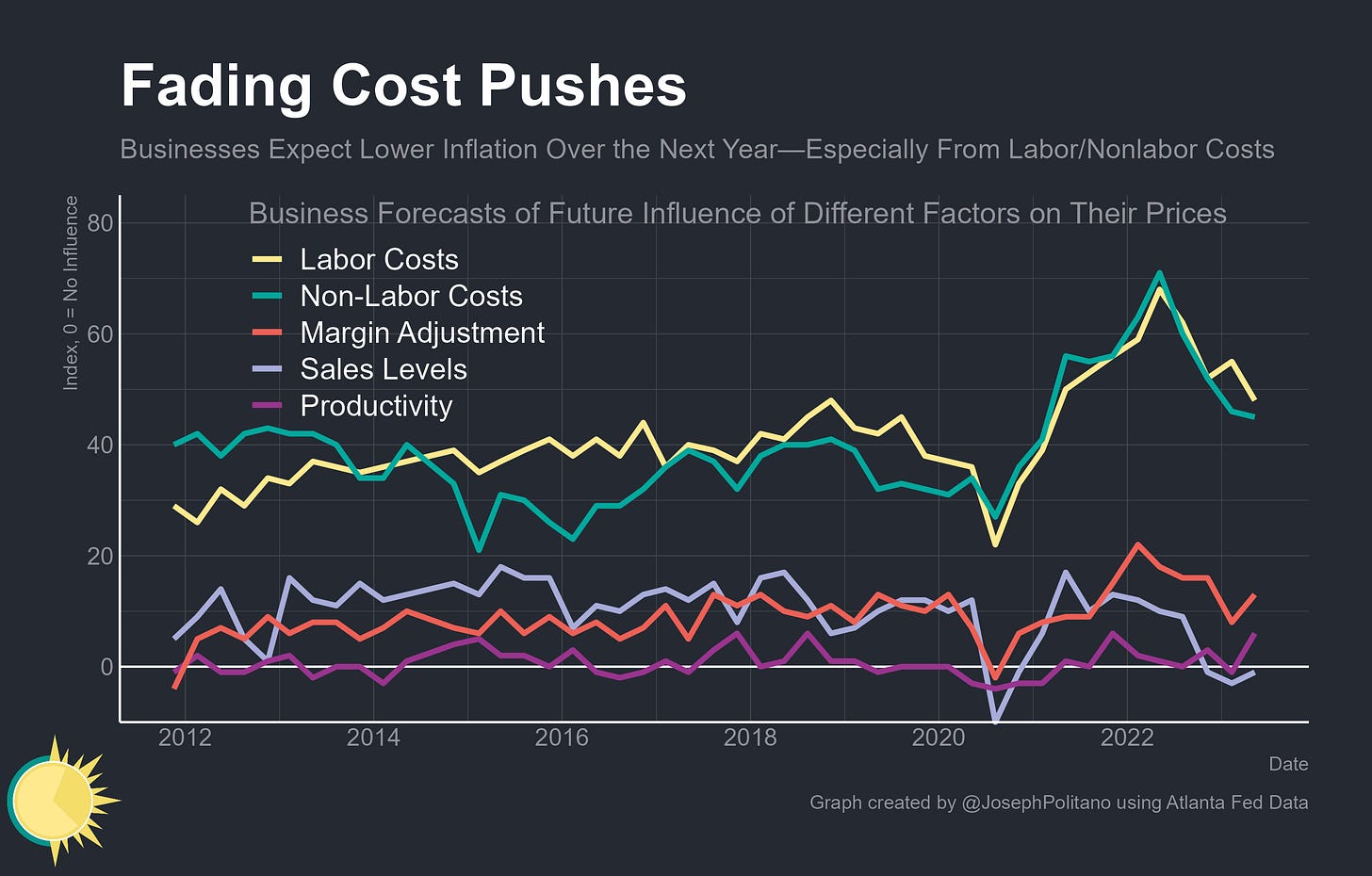

Businesses also expect cost-push inflationary pressures to abate significantly over the next year—with companies in the Atlanta Fed's Business Inflation Expectations survey seeing upcoming labor and nonlabor cost pressures at the lowest levels since early 2021. In fact, the expected influence of labor cost pressures has almost completely normalized and now matches the pre-pandemic highs seen in late 2018. Note, however, that firms also expect changes in sales levels to have a negative influence on inflation in contrast to historical norms—in other words, companies see disinflation coming at the cost of a major slowdown in the US economy.

Plus, companies aren't fully convinced inflationary pressures are gone entirely—year-ahead inflation expectations from the same Atlanta Fed survey are at 2.9% and have been bouncing around the 2.8%-3.1% range for several months now, compared to a consistent 2% pre-COVID average.

Markets, too, do not think inflation will fully return to the 2% target until at least 2024. ICE's US Dollar Inflation Expectations Index, which aggregates market-based inflation expectations from CPI swaps, inflation-linked Treasury bonds, and other sources, sees CPI closing 2023 at just under 3% and 2024 at just under 2.1%.

Longer-run inflation expectations, meanwhile, continue to be anchored. In fact, 5-year and 5-year forward inflation breakevens are currently at the very low end of a level consistent with the Fed's 2% inflation target, and they've been contained within a suitable range for nearly a year now. Persistent, long-run, structural inflation is still not something markets see happening from here.

Growth and Inflation

The US economy has decelerated meaningfully since the Fed started raising interest rates, but real growth is still positive, unemployment is still low, and the US has avoided a recession so far. Keep in mind that we are now nearly one year removed from the two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth that sparked peak recession fears in 2022, and if anything real growth has increased since then. It should therefore not be much of a surprise that we're only now seeing meaningful progress on core services inflation—and that markets and businesses still expect inflation to be above the Fed's target by the end of this year. Underlying nominal income and spending growth have come down significantly but are still too high for 2% inflation, and it will take time for them to fully return to normal pre-COVID levels. Yet it's clear the absolute worst of core inflation is now over, and the gradual descent to normalcy has begun.

Another numbers tour de force.

Great visualizations! Especially the decomposition above trend. It shows how real marginal cost has remained elevated since the pandemic and even the goods sector that many have thought has normalized, appears to still have significant issues. Only until real marginal cost drops will we see an elevated inflation rate.