CPI Inflation Was 6.8% Over the Last Year. What's Driving Red Hot Inflation?

Energy, Cars, Gasoline, Housing, and More

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by 0.8% in November, driving year-on-year inflation to a staggering 6.8%. Core inflation, meaning CPI excluding food and energy, rose by 0.5% month-on-month and 4.9% year-on-year. Prices for used cars and trucks, which have grown almost 40% since 2020, jumped up 2.5% in November. Gasoline prices rose a staggering 6.1% in the month, with fuel oils rising 3.5%. Housing prices, which make up almost a third of CPI, rose 0.5% as well. CPI has significantly exceeded its prior 2% trend, as has the Federal Reserve’s target measure, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI).

While headline figures are very hot, metrics of core inflation are running measurably behind. Core PCE inflation, which excludes food and energy, is running nearly a full percentage point lower than headline inflation on an annual basis. Trimmed mean PCE inflation, which excludes the components with the most and least change, was only 2.6% over the last year. While inflation is undoubtedly becoming more broad based, it remains largely driven by unprecedented price increases in the goods sector where Americans continue to spend a disproportionate share of their income. Aggregate nominal incomes remain mostly on-trend, so inflation will likely subside with the pandemic as consumers renormalize their spending patterns. To the extent that low vaccination rates and the emergence of new variants prevent renormalization, high goods prices are likely to persist.

Gasoline and Cars

Headline inflation has been driven by a strong rise is prices for energy of all stripes including gasoline, motor fuel, and utility gas service. In the last year, gasoline prices have risen 58% and utility gas prices have risen 25%. While 50% fluctuations in gasoline prices are not terribly uncommon (energy is excluded from core inflation for a reason), the current price jumps in utility gas prices have not been seen since the 2008 recession. Natural gas prices themselves have been on a tear recently as global demand spikes. China is importing record levels of US liquefied natural gas in an attempt to cope with an ongoing coal shortage and high energy demand for the winter months. Meanwhile, natural gas prices in Europe have gone parabolic as the continent runs out of domestic reserves, struggles to secure foreign imports, and is embroiled in a geopolitical fight with Russia—from which it imports 30% of its natural gas consumption.

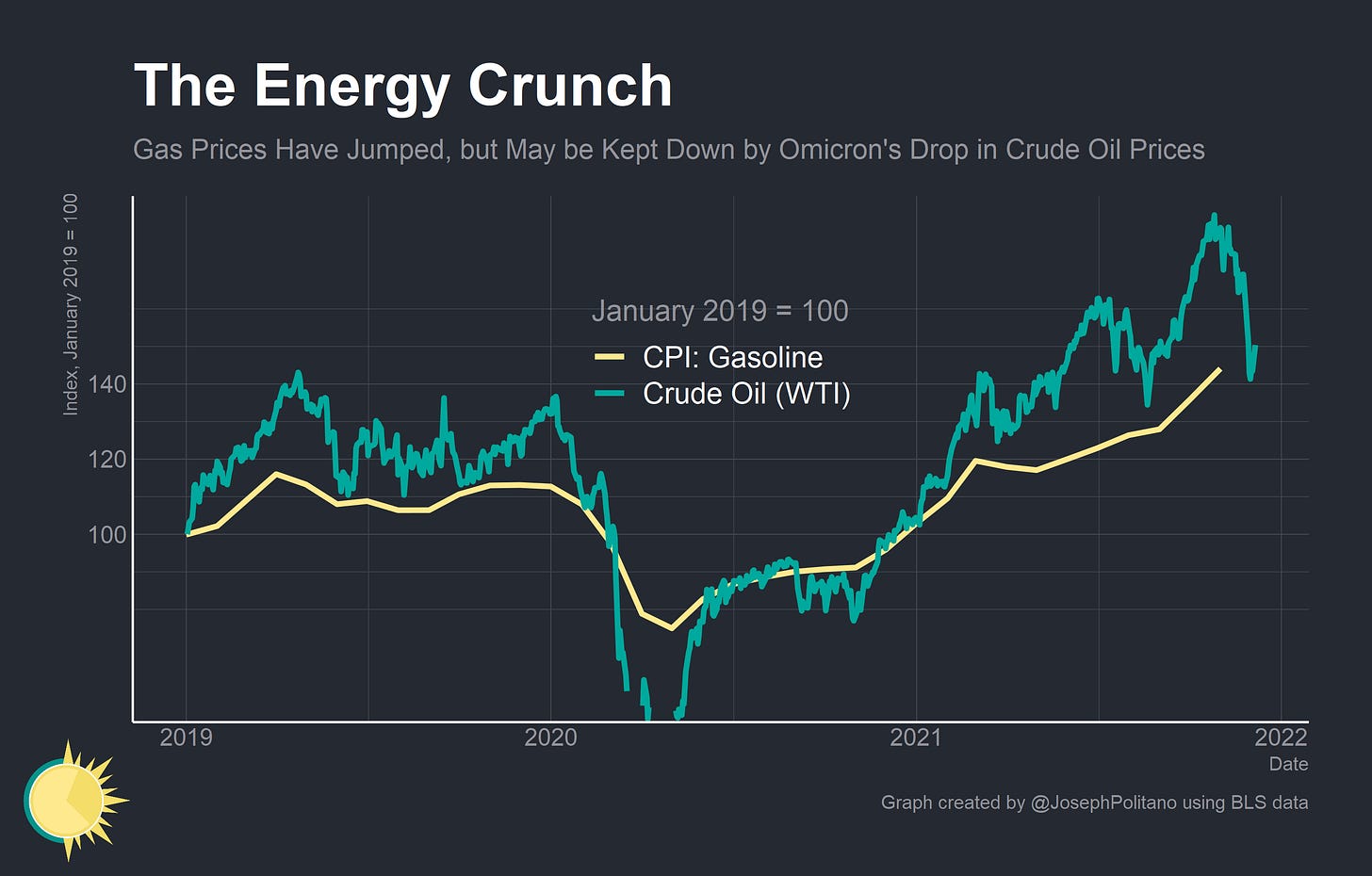

Gas prices have also jumped ahead of pre-pandemic levels as heightened demand meets decreased supply. Americans are, in aggregate, driving as much as they were pre-pandemic—and passenger vehicle travel is up significantly. Meanwhile, US oil companies are struggling to get production back to pre-pandemic levels. The lower margins on US shale production make the industry much more susceptible to shifts in oil prices than many foreign competitions, and the recent 15% dip in oil prices caused partially by the Omicron variant will likely have scared many of them off from increasing production. Incidentally, this drop in transportation demand caused by Omicron will likely tamper future gas price growth. As will the planned output increase by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). The Energy Information Administration’s current forecast expects global oils stock drawdowns to end by Q1 2021.

Cars have also seen unprecedented price increases as global manufacturing stoppages have contributed to an acute shortage of vehicles. Used cars and trucks have increased in price by 31.4% over the last year and 2.5% in November. These shortages do not appear to be abating anytime soon—Toyota has again temporarily suspended production in two Japanese factories while American output remains approximately 10% below pre-pandemic levels. It is worth noting that private sector data has shown higher vehicle prices than CPI, so there is a strong possibility of official measures increasing over the next couple months.

The Home Front

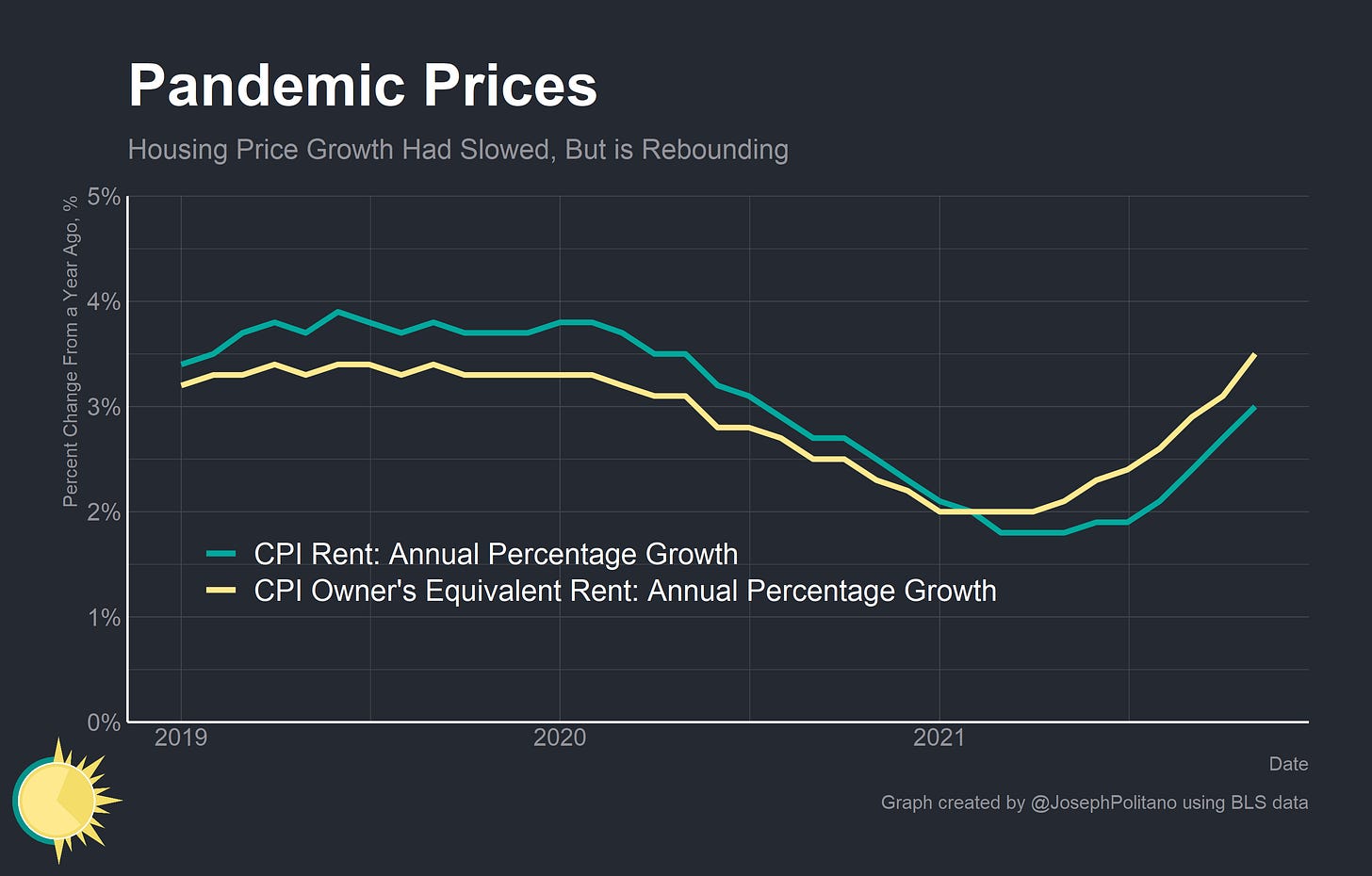

Homes, and real estate in general, are at the forefront of the post-COVID shift from goods spending to services spending. At the onset of the pandemic household formation (the process of usually-younger people moving out of existing households and starting their own) dropped significantly and household consolidation (the process of people merging households, usually by moving in with existing family members) rose significantly. The result was a sharp dip in rent price growth as housing demand shrunk. Now the trend is reversing: household formation is rising and rent price growth is rebounding. Given that shelter makes up 1/3 of the CPI basket, any movement in rents has strong effects on headline inflation measures.

However, there is more to this story than meets the eye. Many workers, either jobless or working from home, moved to lower-cost cities during the pandemic. Many of these lower-cost cities are building additional housing to accommodate new residents—single family home permits are up nearly 50% in Dallas since the onset of the pandemic. The result is that movers are paying less for housing overall, but the CPI’s methodology sees the price growth in low-cost metros as a jump in inflation and does not properly account for substitution.

Prices for lodging away from home, which is mostly hotels and the like, has also jumped ahead of pre-pandemic levels. While business travel and foreign tourism have dropped off significantly since the start of the pandemic, Americans are on aggregate travelling at increasing frequency. Demand for COVID-safe accommodation is high, especially as many travelers want extra time in order to quarantine. The result is that hotel occupancy has exceeded pre-pandemic levels and shows little sign of slowing down.

Conclusions

Overall, aggregate incomes and spending remain largely on-trend—casting doubt on the possibility of sustained inflation. Consumers cannot spend more money than they earn, and long run inflation is determined by nominal income growth. Americans are already acting as though they believe pandemic price increases will abate—the share of consumers looking to buy large household items because they expect prices to increase is slightly below normal levels.

COVID has represented an unprecedented global economic disruption, and it is worth keeping in mind that the consequences have been felt globally as well. Inflation is relatively high in Germany, Spain, Canada, and the UK just as in the US. Consumers in most high-income nations across the globe are still spending more on goods than they were pre-pandemic, and the global increase in goods prices will not abate until spending fully rebalances. Policymakers looked to stabilize aggregate incomes in order to avoid the disaster of the 2008 recession, and a byproduct of preserving people’s incomes is today’s burst of worldwide inflation.

Nevertheless, we will likely receive further new of monetary policy tightening from the Federal Open Market Committee’s meeting next week. Do not expect an explicit announcement of rate hikes—Fedwatchers are not betting on that to happen until the March or May meetings . Nevertheless, the Federal Reserve will be looking to keep income growth on trend in order to prevent unnecessary inflation. At this point, the strength of the recovery and the path of inflation rests in their hands.