Inflation Hits 7.9%, and Things are Likely to Get Worse Before They Get Better

The Russian War Against Ukraine Will Likely Push Up Inflation in the Short Term

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

Inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), was 7.9% over the last year. Even using the more comprehensive Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI) preferred by the Federal Reserve, inflation is still just above 6%. In particular, February saw an acceleration in price growth driven mostly by increases in oil prices—although growth in food and shelter prices also contributed significantly.

However, the worst is yet to come: February’s CPI readings did not capture most of the commodity price changes that occurred after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last month. The CPI collects data throughout the month, meaning that February’s release only partially accounts for the rise in prices that occurred in the last few days of the month. Expect rising oil and food prices to contribute significantly to inflation in the next couple months barring additional geopolitical events that change the course of global markets.

Russia, Ukraine, and Commodity Prices

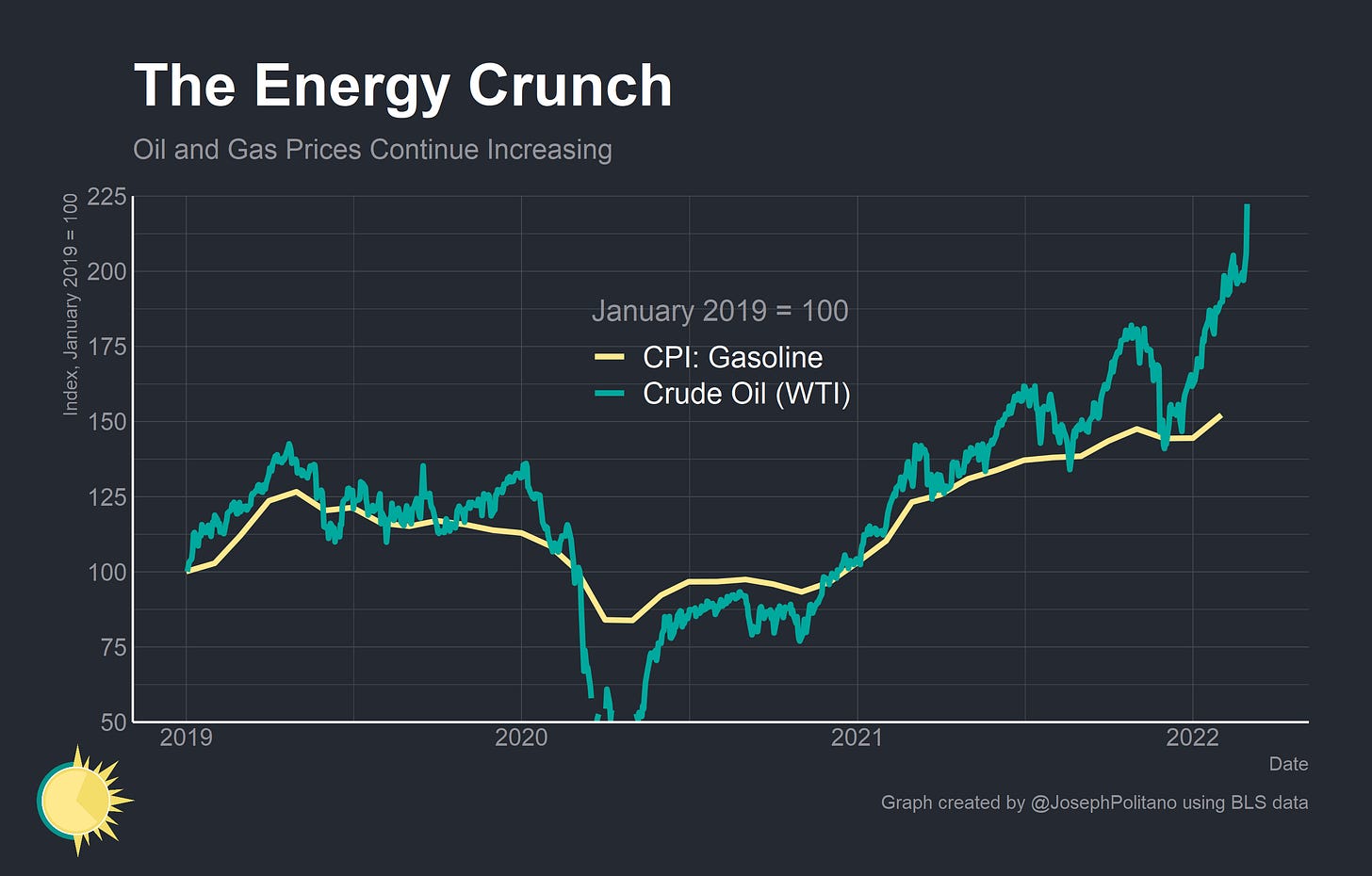

Gasoline prices, always the most volatile of the major price indexes that make up CPI, jumped up 6.6% in February. This represented nearly 1/3 of the total monthly increase in CPI—and gas prices will likely continue to contribute significantly to inflation in the coming months. Russia remains a major exporter of crude oil and natural gas, and tumult surrounding its willingness or ability to continue supplying global energy markets has caused the price of oil to jump significantly and become more volatile.

The US and Canada have banned imports of Russian oil and gas—a largely symbolic gesture given the small role Russian imports play in North American energy markets and the global nature of oil markets. In fact, most of the economic sanctions that many large economies in Western Europe and North America imposed on Russia in response to the invasion had specific cutouts for energy exports. Many European countries are physically dependent on Russian gas—home heating systems run on piped natural gas that originate in Russia—and they cannot afford to lose that access. In theory US natural gas could be converted into Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) and shipped to Europe as a stopgap, but the US doesn’t have enough liquefication capacity and European countries do not have the terminal capacity necessary. Germany, one of the biggest consumers of Russian gas, has no LNG terminals—though Chancellor Olaf Scholz is working on building some domestic terminal capacity. For the time being, Russian oil and gas will continue flowing to Europe.

But how much? Even before the war, Russian natural gas exports to Europe were running at about 1/2 of 2019 levels and total Russian oil output was running marginally below pre-pandemic levels. Wars are ruinously expensive, and Russia could easily see a jump in domestic oil consumption by combat troops and a drop in output due to the redirection of resources. Even though sanctions exempted the energy sector many energy giants are leaving Russia entirely: BP is exiting its nearly 20% stake in Russian oil giant Rosneft, ExxonMobil is discontinuing operations at the Sakhalin-1 project that produces 250,000 barrels per day while foreswearing new investment in Russia, and Shell apologized for purchasing Russian crude while agreeing to cease operations in the country.

Political leaders in the US are searching for ways to boost aggregate oil output in order to contain prices, with the Biden administration in talks with Venezuela to ease sanctions and pushing domestic producers to make up the difference. It’s no wonder why: if oil prices remain at their current levels, the Consumer Price Index could increase by 1% due to gas prices alone. Although it is worth using caution in forecasting oil's (or any commodity's) impact on inflation as volatility is still high and new events (like increased lockdowns in China) could affect global oil prices.

Russia and Ukraine are also key exporters of agricultural commodities—most importantly wheat and ammonium nitrate (a key ingredient in many fertilizers). Together the two countries produce more than 5% of global ammonium nitrate supply and 15% of global wheat supply1—and wheat futures prices have therefore skyrocketed as a result of the Russian invasion. This will likely boost inflation in the medium term, but will not have nearly the same level of impact that rising oil prices do. Wheat is only one ingredient in a subset of food prices, and prior large rises in wheat prices have not boosted final prices of foods by proportionate amounts. Keep in mind that for wheat (and oil) the US is a major global producer—it is countries like Egypt who import large chunks of their wheat that will be most negatively affected. Still, commodity price increases will show up in inflation in the next few months.

Two final items of interest: Noble gases and Palladium2. Russia’s steel industry produces Neon and Ukraine processes that Neon for use in lasers for semiconductor manufacturing. Palladium is also used in semiconductor manufacturing, but is more importantly a core part of catalytic converters on cars. This is critical because motor vehicles alone are responsible for about 2% of the 7.9% inflation over the last year as the global semiconductor shortage impairs manufacturing. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has the potential to worsen automobile supply chains as 70% of global semiconductor grade Neon comes from Ukraine and 40% of global palladium comes from Russia. The good news is that businesses do not seem worried at the moment about extremely bad supply disruptions: the Semiconductor Industry Association said the sector “has a diverse set of suppliers of key materials and gases, so we do not believe there are immediate supply disruption risks related to Russia and Ukraine.” Manufacturers have seemingly stockpiled significant Neon inventories during the pandemic and has somewhat diversified suppliers after the 2014 annexation of Crimea. Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs expects no direct impact on semiconductor materials or production activities, which is important given Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s elite status in the chip market. The picture is less rosy in the car industry—JD Power and LMC Automotive cut their expectations for global light car production by 400,000.

Durable Downside, Service Upside

Circling back to the CPI data, the mid-year trends to look out for remain the same: durable goods prices are likely to moderate or decline as the pandemic abates and services prices are likely to increase as consumer spending patterns renormalize. February was the first time since mid-2021 that used vehicle prices began shrinking, and they are likely to decrease further in the coming months (Russia-Ukraine production issues notwithstanding). Higher-frequency data from the Manheim used vehicle value index shows used car prices declining 2.2% over the month of February. Also, total motor vehicle assemblies were about 500,000 higher in February of 2022 than in February of 2021, though still nearly 2 million below 2020 levels.

On the flipside, prices in the services sector are rapidly increasing. Rents and owner’s equivalent rents, which together make up about 1/3 of the CPI, are experiencing price acceleration. February saw the highest monthly percentage increase in rent prices since 1999 and saw the highest monthly percentage increase in owner’s equivalent rent since 2006. Some of this is catch-up as rental price growth was extremely depressed in 2020 and early 2021 and is only now returning to its pre-pandemic trend. Still, rental price growth moves slowly and with long lags to changing economic conditions so expect it to continue apace in the short term.

Throughout late 2020 and all of 2021, inflation was dominated by durable goods (in particular motor vehicles) increasing in price while a variety of services saw relatively low price growth. This is extremely abnormal as durable goods prices tend to decrease over time due to technological advances and services prices tend to increase over time alongside the value of labor. In fact, it is so unprecedented that a relative price shift of this size has never happened before—the closest America has ever gotten was in 1974. February saw a significant jump in aggregate durable goods prices, but this was evened out by the jump in services prices—so for the first time since early 2021 the relative prices of durable goods stayed flat. Relative durable goods prices could start declining in the near future, indicating the alleviation of pandemic-driven shifts in demand.

Outlook

About this time last year, relatively high inflation was primarily driven by base effects. In other words, prices were disproportionately low in March 2020 due to the pandemic, so when prices hit “normal” levels in March 2021 the growth from 2020 to 2021 appeared distressingly high. Inflation since then has been from a “normal” level—in other words price growth has been in excess of pre-pandemic trends.

Starting soon, the reverse will start happening. Prices in mid-2021 were disproportionately elevated, so the base effects will start working to lower inflation. Still, that will require month-on-month price growth to decelerate over the short term, and that deceleration will likely have to come from drops in durable goods prices (or commodity prices, depending on how geopolitical events go) or non-housing services. A lot of rent price growth will be “baked in” because movements in rental markets translate to the CPI on a delayed basis.

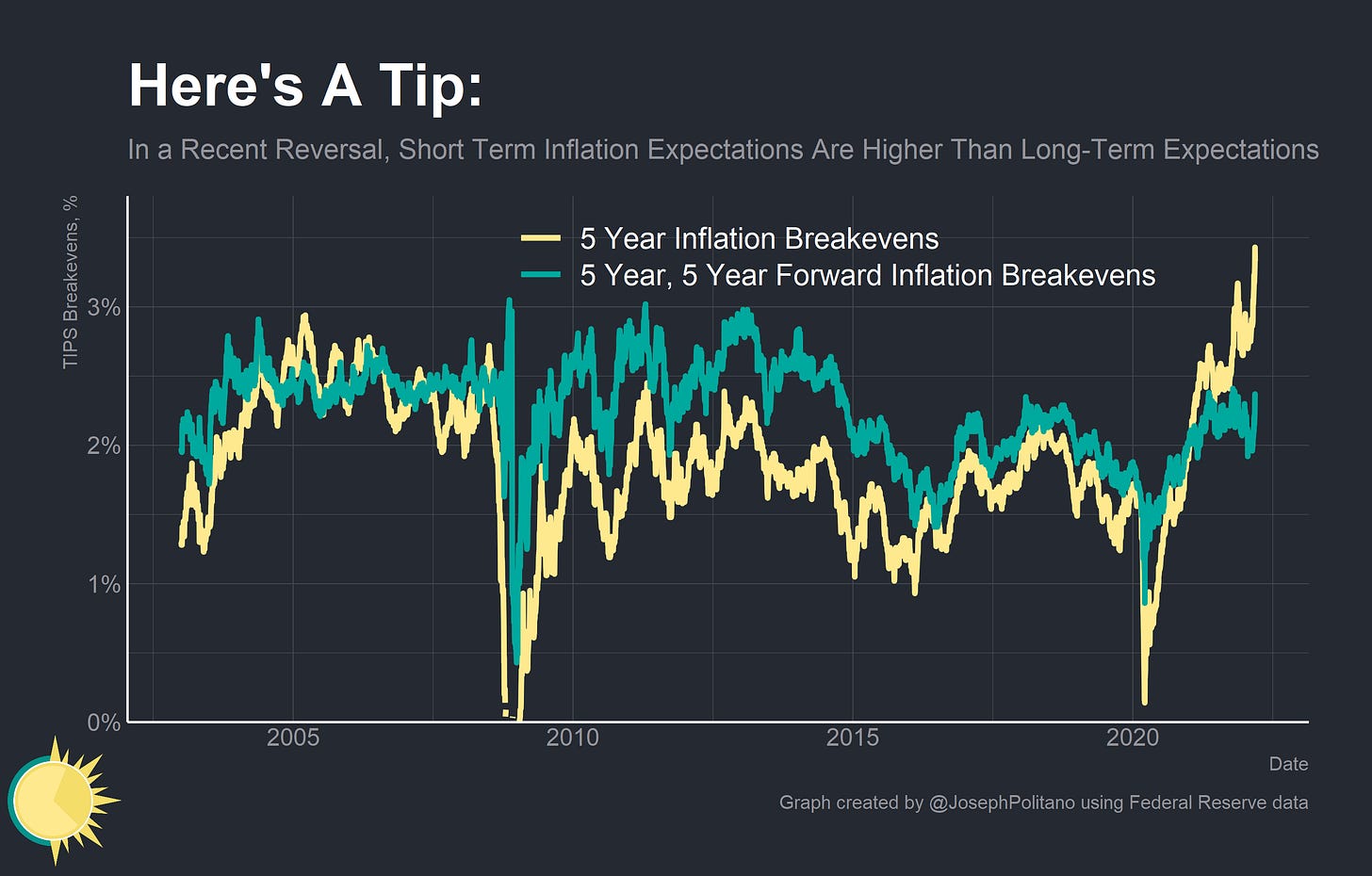

Inflation expectations, as measured by the yield differentials between inflation protected and non-inflation protected bonds, are increasing for the short term. A lot of that has to do with rapidly changing expectations surrounding commodity prices and other items that directly feed into inflation. Longer run inflation expectations, however, remain functionally unchanged over the last 9 months.

I hate to always sound like a broken record on this, but in truth it is extremely important to constantly emphasize. Personal income remains on the pre-pandemic trend, and personal outlays are only slightly above trend as consumers spend down some of their excess savings. Since nominal aggregates are the method through which the Federal Reserve controls inflation, monetary tightening is justified only to the degree that it is controlling these nominal aggregates.

A previous version of this article said that Russia and Ukraine represented 60% of ammonium nitrate supply and 30% of wheat supply. This was their share of global exports, not their share of global production. I apologize for the error.

I would be remiss not to directly cite Maroon Macro, who did a great research piece on the effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on global supply chains. You can read it here:

After all is said and done, one thing is maybe clear. If Powell successfully navigates the storms ahead, he will be “hailed”. After all, with all the “disasters” Bernanke “promoted”, he was hailed “The Hero” by The Atlantic and got named “Man of the Year” by time magazine!

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/the-fed-and-war?s=w

Dear Mr Politano, let me draw your attention to your comments regarding Black Sea wheat. Russia and Ukraine account for 30% or world trade, NOT total supply which s much bigger. But this is bad enough as world trade is the dinamic part of the equation. Additionally this region has been the “price fighter” in grain & oilseeds markets over the past 20 years and created a big dependence on many importing countries. This has been to the detriment of other market players like the US, Argentina, Europe and Brasil (oilseeds). Perhaps this was VP’s game plan from the very beginning. Very sad.

Suscriber Pedro Rodriguez