Mr. Crypto Goes to Washington

Points of Recentralization are Allowing Governments to Regulate Crypto Markets

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing, you’ll join over 4,300 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, America imposed some of the most stringent financial sanctions possible on the Russian government, its businesses, and a ream of high-powered individuals. Almost instantly, large chunks of the country and millions of people were cut off—partially or fully—from the global financial system. American financial institutions were required by law to exclude many of them, and many more were excluded as a precaution in case of further sanctions.

So what’s an internationally condemned economic pariah to do? The next step seemed logical; start working outside the traditional financial system. Cryptocurrencies are designed explicitly to sidestep the exact kind of financial regulations that Russia found itself under, so perhaps Bitcoin could allow the Kremlin to carry on its international trade despite sanctions. Not so much—Coinbase, America’s largest crypto company, announced that it would be blocking the addresses associated with sanctioned Russian individuals and institutions-as did Binance and all other major cryptocurrency exchanges. “Sanctions play a vital role in promoting national security and deterring unlawful aggression, and Coinbase fully supports these efforts by government authorities,” the company said in a public blog post. Total Ruble/Bitcoin transactions jumped after the initial invasion, but sank to below pre-war levels shortly after.

Cryptocurrencies were founded on radical ideals—a trustless, decentralized system that would be beyond the reach of the state and eliminate the kind of centralized intermediaries responsible for the 2008 financial crisis. An ideal cryptocurrency system would be immutable, impervious to attack, free from government interference, and impossible to regulate.

In the first stage of the crypto economy, that generally held true. Bitcoin’s volatility made it a difficult-to-use currency, but its decentralized network facilitated transactions that bypassed virtually the entire established global financial system. At its best, that meant users were able to sidestep the strict rules imposed by brutal dictatorships. At its worst, it meant users could participate in an underground economy of illicit goods and black hat cyber criminals. While traditional policing could prevent some of the worst abuses—smuggling still required physical smugglers, even if transactions are digitally secure—there was nothing most governments could do to influence the Bitcoin network itself.

But this fully decentralized payments network introduced its own suite of problems. Transactions were immutable—which meant there was no way to undo mistaken or fraudulent transfers. Accessing the system meant individually setting up and maintaining a network of personal wallets, and a forgotten password could be the end of your crypto investment. “Cashing out” back into US dollars was extremely difficult, as you had to find a way to interface back with the traditional financial system. Even crypto transactions themselves became difficult as transaction volumes outgrew the limited capabilities of most cryptocurrency networks.

In the second stage of the crypto economy, a growing network of intermediaries began to sprout up in order to solve the problems of a completely decentralized system. Miners began forming pools to increase efficiency and split profits. Exchanges and layer 2 systems helped facilitate additional transactions. Stablecoins—centralized crypto tokens that are pegged to fiat currencies, usually the dollar—emerged to connect the traditional and decentralized financial system. Metamask provided easy-to-use online wallet management bridged that helped bridge the accessibility. Companies like Coinbase provided access to the whole crypto economy through a simplified phone app.

In the third stage of the crypto economy, which we are currently living through, these centralized systems are in constant competition-and-cooperation with their decentralized counterparts. The decentralized financial protocols are reliant on the centralized aspects of many providers, and users interested in decentralized assets mostly access them through centralized services. As my friend Kyla Scanlon explained, this has mostly driven increased choice for consumers as different providers stake out different spots along the centralized vs decentralized axis. But it has also had another important consequence: the points of recentralization in the crypto ecosystem have enabled governments to directly regulate the decentralized economy for the first time.

Cryptocurrencies’ futures are therefore increasingly dependent on the decisions of lawmakers and other traditional points of political authority. In recent years, crypto firms have increasingly found themselves on the wrong ends of drubbings by financial, business, and environmental regulators across a variety of countries. They are also increasingly playing by the rules—or at least taking the rules more seriously. On the flip side, power players in the crypto space are increasingly making a splash in the political realm—looking to shape the rules their economy will operate under.

Crypto at Scale

To understand how cryptocurrency regulations are emerging, it is first necessary to understand what “points of recentralization” are and how they’ve emerged in the crypto ecosystem. The first example is due to demands from scaling up crypto networks. Take Bitcoin as an example—the coin was designed as a near-explicit counterweight to the centralized points in traditional financial systems. Over time, however, the Bitcoin network scaled up so much that maintaining total decentralization was nearly infeasible. Mining is the process through which bitcoin transactions are verified and new Bitcoins are created, and as such it is essential for the basic functioning of the Bitcoin network. Theoretically any reasonably-capable computer would be able to participate in mining, but over time the price of Bitcoin rose so high and network demand became so large that miners needed to scale up. Miners pooled their resources and agreed to share profits in order to survive in the competitive environment, but even that wasn’t enough. Eventually Bitcoin mining grew to require the economies of scale delivered by industrial warehouse space and industrial electricity consumption to remain competitive.

In this way mining—the process that underpins proof of work cryptocurrencies—went from a clandestine network of thousands of computers to a blaringly obvious network of thousands of massive techno-foundries. Modern cryptocurrency mining has electricity consumption patterns that are so distinctive that they might as well be bright neon signs telling governments where to find them.

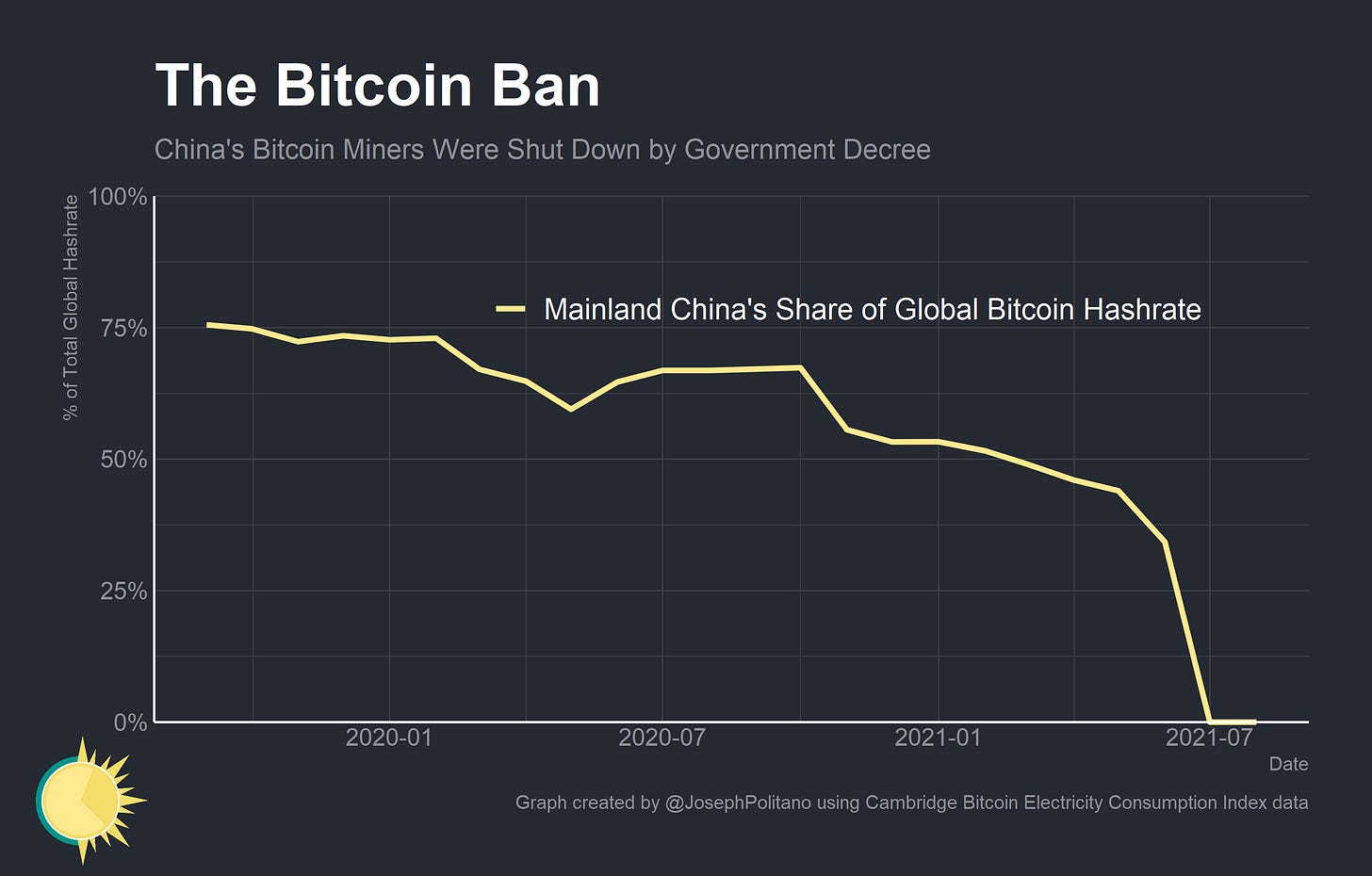

That kind of identification made it easy for the Chinese government to extinguish its domestic cryptocurrency mining operations virtually overnight1. The government has grown increasingly distrustful of a system that could provide censorship free transactions and—critically in China’s case—evade the country’s strict capital controls. They were willing to tolerate mining because the country’s industry had a massive market share and was reasonably profitable, but a nationwide power shortage proved the straw that broke the camels back. While some miners operated for a bit after the official ban and underground mining likely still occurs, the vast majority of China’s mining enterprises were snuffed out rather quickly.

The other main points of recentralization are the platforms and financial intermediaries that gatekeep much of the modern crypto space. As an example, OpenSea has become a centralized platform for access to the Non-Fungible Token (NFT) marketplace. OpenSea verifies collections and creators, bans malicious actors, and has even intervened to freeze trading on NFTs whose blockchain transactions were fraudulent. OpenSea—a centralized service—is effectively able to dispute on-chain transactions that it labels fraudulent, essentially allowing the company some power to regulate and adjudicate the decentralized NFT economy. And they’re far from the only company with the ability to regulate the crypto economy.

For example, we have methods for identifying accounts held by sanctioned individuals outside of Coinbase, even if we don’t have direct access to their personal information. For example, when the United States sanctioned a Russian national in 2020, it specifically listed three associated blockchain addresses. Through advanced blockchain analysis, we proactively identified over 1,200 additional addresses potentially associated with the sanctioned individual, which we added to our internal blocklist.

Coinbase, “Using Crypto Tech to Promote Sanctions Compliance”

These large companies are essentially forced by their size to formalize themselves in the real world—they register as corporations, choose CEOs, file taxes, etc. As a result of these companies’ size and official stature, regulators have significant leverage over them—and indirectly over the crypto marketplace. Large, publicly traded financial companies like Coinbase have to follow the same kind of know your customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) rules that traditional financial companies do. In practice, this requires that users verify their identities so that tax agencies, regulators, and law enforcement could access their records if needbe. The law also essentially forces crypto firms to perform significant amounts of data analysis on publicly-available blockchain records in order to verify that they are not dealing in laundered money. Companies have banned users for accessing mixers—services designed to mask crypto transactions—and have identified and blocked transactions in tainted cryptocurrencies.

Possibly the biggest points of recentralization come when the traditional and decentralized financial worlds have to interface—usually through stablecoins. These tokens represent billions of dollars in financial assets and process billions of dollars in transactions daily. Since stablecoins must maintain a peg to a traditional currency they have significant presence in the much more heavily-regulated world of traditional banking. Most major stablecoins are registered with the US Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), forcing them to follow rudimentary KYC and AML protocols as well as file major transactions with the US government. Most major stablecoins are also registered with state financial services departments (the vast majority of stablecoin volumes are in US dollars), forcing them to follow investment and balance sheet rules designed to prevent fraud and reduce the risk that the companies go under—leaving customers out to dry.

Tether, the largest of the stablecoin issuers, has long played fast-and-loose with traditional banking regulators, but even they are being brought to heel. Previously, they’ve avoided registering with US regulators, concealed the components of their balance sheet, and operated with few reassurances for users. That was until the New York Attorney General (NYAG) brought Tether to court for deceiving users that Tethers were always backed by dollars and using Tether’s assets to cover losses in their sister company Bitfinex. The NYAG also forced Tether to begin disclosing the composition of assets it uses to back the stablecoin, allowing users to finally see Tether’s balance sheet. Since being in the public eye, Tether has moved into safer assets (primarily US Treasury Bills)—though their balance sheet likely remains too risky. Still, it is a microcosm of how traditional government institutions are influencing the crypto ecosystem.

At its core, the current state of the crypto ecosystem and the hard tradeoffs imposed by blockchain technologies make regulation nearly inevitable. When crypto networks are small they can avoid intermediaries—but now crypto adoption is so high and transaction demand is so strong that networks need intermediaries for basic functions. For networks to remain decentralized, transactions must be publicly displayed on the blockchain—but that same public ledger makes it trivial for governments to track how money moves between accounts. Monero is one coin that attempted to use more sophisticated techniques to encrypt transactions while keeping them on the blockchain—but has run into plenty of problems because of it. Some major exchanges refuse to deal in Monero in specific countries due to regulatory pressure, and recently a group of Monero users became convinced that some exchanges were using the coin’s encrypted ledger to conceal the fact that they were selling fake Monero that is unbacked by real reserves. The reality is that crypto is growing up and now has to interact with the real-world institutions that it was designed to bypass.

Crypto and K Street

The move-fast-and-break-things attitude of Silicon Valley is increasingly catching up with many crypto firms as regulators crack down on “the wild west of finance”. Coinbase was banned from launching “Coinbase Lend”, a 4% interest rate on stablecoin deposits that the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) considered a security. The SEC was right in its designation, but plenty of decentralized providers have been able to issue similar financial products simply by virtue of not having to answer to the SEC. The Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has banned cryptocurrency prediction markets and instituted enforcement actions against unregister crypto derivatives providers. The real wake up call came in the recent infrastructure bill passed through congress; “brokers”, an ill-defined term within the crypto space, will have to report transactions to the IRS for tax collection purposes. The crypto political community attempted to mount a defense in order to strike the language or at least clarify its intentions, but was unable to meaningfully change the bill.

With government regulation assuming a more critical role in the crypto ecosystem, cryptocurrency companies are responding by assuming a more critical role in the regulatory ecosystem. Corporations are forming trade associations like the Chamber of Digital Commerce, Blockchain Association, and Crypto Council for Innovation. Think tanks like CoinCenter are growing in influence and multiplying in number. Research from The Economist and The Washington Post show that crypto lobbying firms and large crypto companies are spending millions on hiring new staff and launching Political Action Committees (PACs). There is even a Congressional Blockchain Caucus now.

Crypto firms are also working at the state level to influence their political acceptance. After a large amount of work from crypto users and crypto firms, Wyoming passed a network of laws building a clear framework for digital depository institutions and decentralized organizations in the hopes that it would attract additional investment from the industry. Their gamble proved successful as crypto organizations like Kraken, Cardano, and Ripple moved to the state. Texas’s industrial and energy rules have made the state a haven for Bitcoin miners, and cities like Miami are attempting to become national cryptocurrency centers.

Cryptocurrency is also likely to become an increasingly partisan issue as its saliency rises. Lawmakers can cross the aisle to work on crypto rules and regulations while the spotlight is on other issues, but if there is one truism in modern politics it’s that public attention drives partisanship and gridlock. As more Americans become aware of or invested in the crypto economy, there is a large potential for heightened attention to drive harsh battle lines between political groups. Appointees for the Federal Reserve will likely be quizzed by the Senate on their cryptocurrency opinions, as will appointees for federal agencies and regulators. If federal lawmakers can’t pass new bills regulating the crypto space, the rules will instead come from bureaucratic decision making and judicial review. Either way, crypto regulation and crypto lobbying are here to stay.

Conclusions

At some level, cryptocurrencies are following the path that internet technology giants walked many years ago. User generated content was a new invention that made the copyright rules and regulations of the 20th century practically obsolete. Companies like YouTube played fast and loose with regulations, hosting plenty of illegally uploaded copyright content and illicit material. The digital tech companies started butting heads with regulators and the law once they got large enough, and new generations of rules had to be written by lawmakers while regulators wrested control of the space.

Eventually, we got a system of digital rights management and digital content management that works reasonably well for all parties. Automated systems protect against copyright infringement and ban people who abuse the platforms. Users have well-established digital communication rights under the law, and platforms have well-established regulatory responsibilities. When regulators caught up with technology, the system improved.

In the same way, regulation of cryptocurrency has the potential to improve the cryptocurrency system. Like it or not, crypto is not going anywhere soon—and so the abundance of legal uncertainty, systemic financial risks, and fraud in the crypto ecosystem remains a significant problem. Regulation will be a necessary part of crypto’s next evolution, so it is extremely important that lawmakers and regulators get it right. That means making sure that the well being of crypto users are prioritized over crypto firms, passing laws instead of relying only on bureaucratic processes, and ensuring that legal frameworks can incorporate additional healthy innovation in the crypto space.

Unsurprisingly, accurate data collection of decentralized systems is rather hard. The Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index presumes that miners aren’t using VPNs or other services to mask their country of origin (there are good reasons to think this, as high latency can negatively impact mining). An assumption like that means you should not take the results as perfectly accurate, but the massive drop in the total bitcoin hashrate at around the same time means that the bans had a significant impact.