Student Loans are Bad Taxes

America's Student Loan System is Functionally a Tax on Former Students, and it is One of the Worst Designed Taxes Possible

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

In 2010, President Obama completed the near-total nationalization of America’s student loan system. Though the federal government previously set interest rates and guaranteed loans, private banks were allowed to profit directly off of the student loan system. Through nationalization, Obama had functionally made student loans a new form of federal taxation; the government was making a claim on the future income of student loan borrowers. Loans were granted by the government at uniform interest rates not adjusted for risk, could not be discharged through bankruptcy like traditional borrowing, and could not be refinanced through the federal system. Burdens are even decreased for lower income workers through different income-driven repayment plans, again mimicking the tax system more than private borrowing. The government may conceal this reality through the use private student loan administrators like Navient, but the truth is clear; student loans are taxes.

If student loans are taxes, however, they are among the worst taxes designed in the United States. They put significant undue burden on low-income people who have to borrow more money to achieve the same education. They change costs capriciously based on market interest rates. Their regressive structure disproportionately benefits higher-income graduates. Their income-driven repayment options place high marginal tax rates and administrative burdens on low-income students. Even student loan forgiveness is unfairly taxed as additional income.

Given the increasing cost of higher education and the steady growth in the percent of Americans attending college, correcting the egregious student loan system is critical for the country’s economic future. This means constructing a system where lower-income students are not systemically disadvantaged, where interest rates are eliminated, and where marginal tax rates are low and progressive. Irrespective of the benefits or drawbacks of student loan forgiveness, it is clear that the flaws in America’s student loan system will not be addressed until the tax structure itself is changed.

The Student Loan Situation

It is useful to analyze America’s student loan system as a universal grant given to prospective college students tied with an individual income tax given to the students upon graduation. Unlike traditional loans from financial institutions, the interest rates and amount available to student loan borrowers do not fluctuate based on the borrower’s risk level. Both of these are instead dictated directly by the federal government. Nor can the loans be discharged in bankruptcy like traditional loans. This makes some sense, as unlike with a mortgage you cannot foreclose on the borrower’s asset (their knowledge) if they do not repay their loan—but it is still another critical difference between student loans and traditional lending. Lower-income borrowers can enter income-driven repayment plans unlike with most traditional forms of debt. Students are also unable to refinance their loans with the federal government as they would with a traditional bank, and the federal government can garnish wages without a court order if student loans go unpaid. These are all the characteristics of taxes, not loans.

Before evaluating student loans as taxes, let’s take stock of America’s student loan situation. Since the 1970s, student loan debt per graduate has been steadily increasing as tuition costs rose in tandem with the value of a college degree. The income gap between college graduates and non-college graduates has been growing as the technical complexity of America’s economy grows, pulling more students into the higher-education system. The debt for graduates peaking in 2007 due to high interest rates (a graduate in 2006 faced 6.8% borrowing costs) and growing tuition costs. Since then, however, debt has generally stabilized at the starkly high level of $30,000 per graduate. It is worth noting that debt per borrower has continually increased as student loans compounded faster than new workers could pay them off.

In 2021, total student loan debt outstanding hit $1.7 trillion dollars after decades of nonstop nominal increases. Despite the debt per borrower increasing and debt at graduation remaining at high levels, student loan debt has represented a stable portion of American national wealth since 2013. Only the pandemic caused outstanding debt to decrease relative to net wealth, as college enrollment tanked and borrowers were given interest-free forbearance on their loans.

Interest rates have also been regularly decreasing since the passage of 2013’s Bipartisan Student Loan Certainty Act. This law tied the interest rates of all student loans to the interest rates on 10 year Treasury bonds with caps on the maximum values, in the way same way subsidized undergraduate loans were previously structured. It is worth noting here the capriciousness of both the different interest rates charged to different borrowers and the shifting interest rates across time.

As previously, the interest rate structure of student loans are not reflective of the risks of borrower default in the same way that traditional loans are. Instead, the federal government assigns the same interest rate to all borrowers of the same group regardless of any risk profile. Higher rates are charged to graduate students and Parents for functionally arbitrary reasons. This discourages students from attending graduate school or starting undergrad when they are still minors and require their parents to borrow on their behalf.

For two, students are basically stuck with the interest rate of the year they attend college and have no easy way to refinance their loans like traditional debtors. Sure, they can reach out to private student loan companies to refinance, but they must give up significant federal benefits in order to do so. Graduates who refinanced just before the pandemic lost out on more than a year of interest-free forbearance simply because they sought out a lower interest rate. In this way year of graduation can arbitrarily affect the amount a student will end up paying — 2007 undergrad borrowers stared down 6.8% interest rates while 2020 borrowers got 2.73%. This, however, is not the only unfair flaw in America’s student loan tax program.

How Much Do I Owe You?

So given that student loans are taxes, how can we evaluate them? There are several general principles that income taxation should follow. First, taxes should be broad-based meaning that it should encompass as close to all people as possible. Second, it should be progressive instead of regressive. Progressive means that higher-income people are taxed at higher marginal tax rates (the tax paid on an additional dollar of income) than lower-income people. This way average taxes (the total amount of tax paid as a share of income) will also be higher for higher-income people. Third, it should have smooth marginal tax increases. This means that generally marginal tax rates should not increase or decrease rapidly as incomes grow, and there should especially never be a “cliff” where marginal tax rates exceed 100%. Finally, average and marginal tax rates should generally be as low as possible. While there can be significant benefits to public spending, the taxes taken in for that spending should be as low commensurate with long term fiscal stability as possible. This way the deadweight loss of taxation is minimized. With investments like education, which dramatically boost productivity and have massive positive externalities, there is no need to fully pay for the expense through taxes. Some additional growth in the national debt will simply be counterbalanced by growth in national GDP and wealth.

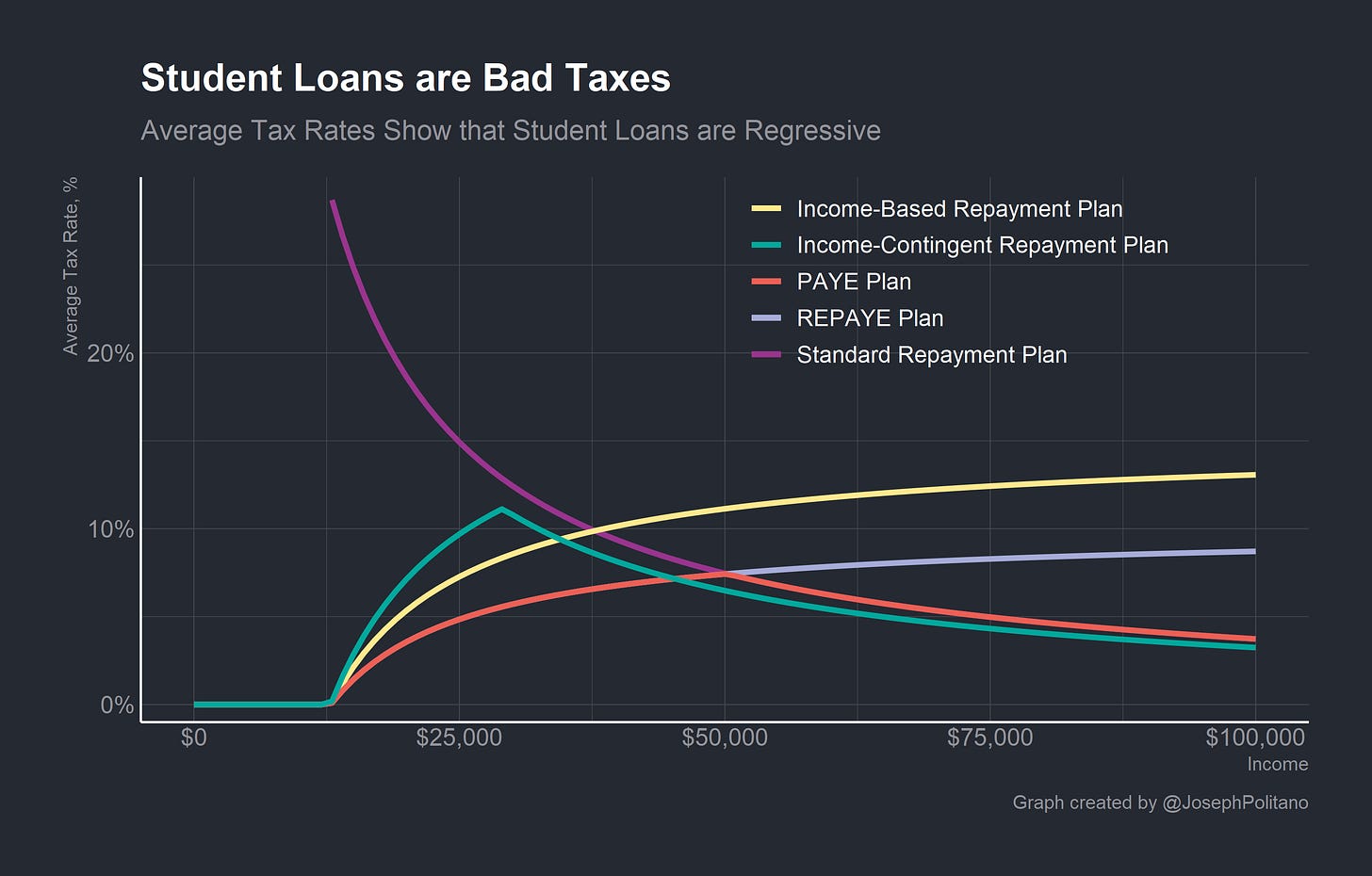

This grossly oversimplifies a rich literature on tax policy, but it is useful to bring up the most basic principles first to see how spectacularly America’s student loan programs fall short. Take this oversimplified hypothetical example of a single, recent graduate with $30,000 in student loans at a 4.5% interest rate. Their monthly payment on a standard 10 year repayment plan would be $310.92, but they could achieve lower repayment amounts if they qualified for income-driven repayment plans.

While the standard repayment plan is effectively a lump-sum tax, income-driven repayment plans more closely match traditional income taxes by claiming a percentage of the borrower’s discretionary income. These plans are designed to help lower-income borrowers by extending the term of their loan, lowering their monthly payments, and in certain cases forgiving the debt after decades of diligent repayment. However, these various repayment plans introduce high marginal tax rates for low-income borrowers. Once you make more than the U.S. Federal poverty line ($12,880 for a single individual and $26,500 for a family of four in the contiguous US) income-driven repayment plans take between 10% and 20% of every dollar you make on top of traditional income taxes. Critically, these plans have both rapid shifts in marginal tax rates and high levels of marginal taxes faced by our example borrower, violating some of the basic rules laid out earlier. They also impose significant administrative burdens on borrowers, as enrollees have to recertify every year.

Average tax rates show that student loan plans are highly regressive, meaning lower income people tend to pay more as a percentage of their income than higher income people. This is even more true when you consider the regressive nature of student loan borrowing itself: undergraduate students from lower-income families tend to borrow more than students from higher-income families.

Looking at the tax rates faced by our example borrower in attempting to minimize their monthly payment also provides some important insights. The borrower faces a 10% marginal tax rate from when they start earning $13,000 a year to when they cross $45,000 a year. At this point the average tax rate has maxed out at a bit higher than 7% and the borrower has switched to the standard repayment plan. These marginal tax rates are extremely high when paired with the traditional federal income tax rate (12% from $9,876 to $40,125 and 22% from 40,126 to $85,525). This also illustrates the regressive nature of the student loan system. If our example borrower makes $100,000 a year their average student loan tax rate is 3.2%, compared with nearly 7% if they make $43,000 a year! This is not even to mention that income-driven repayment plans have longer terms than the standard repayment plan, meaning low income borrowers may end up paying more over the lifetime of the loan.

It is also worth bringing up the concept of tax neutrality and broad based taxation. Tax neutrality is the idea that taxes should not favor one particular type of good or service over another. A tax on oranges that did not apply to apples would be arbitrary and poorly designed. As mentioned earlier, taxes should be broad-based, meaning they cover as much relevant economic activity as possible without respect to specifics. All Americans pay the same federal income tax rates regardless of their profession, for example, although there are holes in the federal income tax system that make it not as broad based as possible. In these respects, student loans fail spectacularly as taxes. Instead of uniformly taxing the population, student loans only tax the narrow subset of people who attended school and had to borrow money in order to pay for it. The amount paid is not a function of the earned income of the taxpayer but rather the tuition they could not pay with their prior income, scholarships, or parents’ help. The interest rates that determine the student loan tax burdens can vary wildly from year to year and are always different depending on the type of borrower (undergraduate, graduate, or parent). All of this comes together to form a barrier for students from low-income families who try to attend university.

Finally, it is worth examining if student loan tax rates are as low as fiscally sustainable. The answer is a resounding no. Education has high positive externalities that justify its subsidization, meaning that the social benefits of education are not fully captured by the individual who attends school. Going to school improves the knowledge of others, increases economic innovation, improves social cohesion, increases aggregate economic productivity, and so much more. Instead of properly subsidizing the higher education system to maximize social benefit, the existing student loan system actually taxes higher education as if it had negative externalities! The mere presence of interest ensures that borrowers will always pay back more than they borrowed as long as they do not achieve forgiveness, which few do. The student loan system has therefore been a profit center for the federal government. Obviously, the system does subsidize borrowing costs when compared with private-sector alternatives, but the subsidies are nowhere near commensurate with the social value of higher education. This needlessly hampers growth and exacerbates inequality throughout the American economy.

Conclusions

If someone proposed changing the tax system used to fund the K-12 system to match the current student loan system they would rightly be ridiculed. The idea of having students individually repay the vast majority of their education expenses to the government as if it was debt makes no sense when applied outside the university context, and it is only because of path dependency that we accept the current student loan system. Make no mistake, there are significant problems with the way K-12 education is funded; the use of local property taxes allow high income, Whiter school districts to exacerbate educational disparities while the state and federal government do not do enough to pursue integrated equality. But these inequalities persist in higher education, and are exacerbated not ameliorated by the structure of the student loan system.

A student loan forgiveness program, while it would temporarily remove the burdens faced by current graduates, would not fundamentally address the root of the problem. The US disburses nearly $100 billion in student loans every year, meaning student loans outstanding could approach $1 trillion within a decade even if we forgave every penny of today’s debt. The real answer lies in reforming the student loan system to meet the needs of today’s students.

For one, interest rates should be eliminated or capped at an extremely low amount. There is no reason to subject borrowers to a cheap facsimile of risk-based pricing. If this is impossible, borrowers should at least be allowed to refinance their loans within the federal system when interest rates decline. The federal government should take a larger role in directly subsidizing the costs of attending college by offering students direct cash allowances in place of student loans. State and local governments should work to make universal tuition-free community colleges and public universities.

It is reasonable to worry that loosening the budget constraints on college enrollees will manifest as significantly higher costs rather than fairer tax burdens and additional educational opportunities. The US, however, already institutes loan borrowing limits alongside fairly strict price and quantity controls for public universities. These controls are not great policies in it of themselves, especially the quantity controls, but to the extent they are allowed to exist the student loan system should be reformed to compliment them. Some also worry that without debt financing students will drift into lower-productivity fields and majors. Putting aside the attempts to control individuals’ personal pursuit of knowledge, students are already offered significant benefits for pursuing high-productivity fields: the higher pay rates in these fields. There is no need to throw poorly designed tax systems on top of this incentive. Softer budget constraints in the higher education system could cause higher innovation throughout the economy as a tradeoff for higher costs in the education sector.

Reforming the student loan tax system will take new federal legislation, but significant reforms could occur directly from the president’s desk. Interest rates could be harmonized, capped, or eliminated through executive order, as has occurred during the COVID-19 crisis. Recurring forgiveness policies from the resolute desk, whether large or small, would act as a subsidy to higher education and significant relief for existing graduates. State representatives should work to expand access to tuition-free alternatives to private school and build increased capacity at state universities. The economy of today and the economy of the future increasingly require higher education to amplify productivity and wealth, and building a fairer system for Americans to access that education is critical to our economic success.

I was revisiting this and noticed https://www.brookings.edu/articles/biden-is-right-a-lot-of-students-at-elite-schools-have-student-debt/ seems to contradict your claim that lower income students "borrow more"...did you mean that more lower income students borrow than higher income / lower income students have a higher P(has_student_loans)? That's what I interpret from Brookings, anyways....