Tariffs are Already Stalling the Economy

Tariff Front-Running is Already Showing Up as Reductions in US GDP Growth

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 60,000 people who read Apricitas!

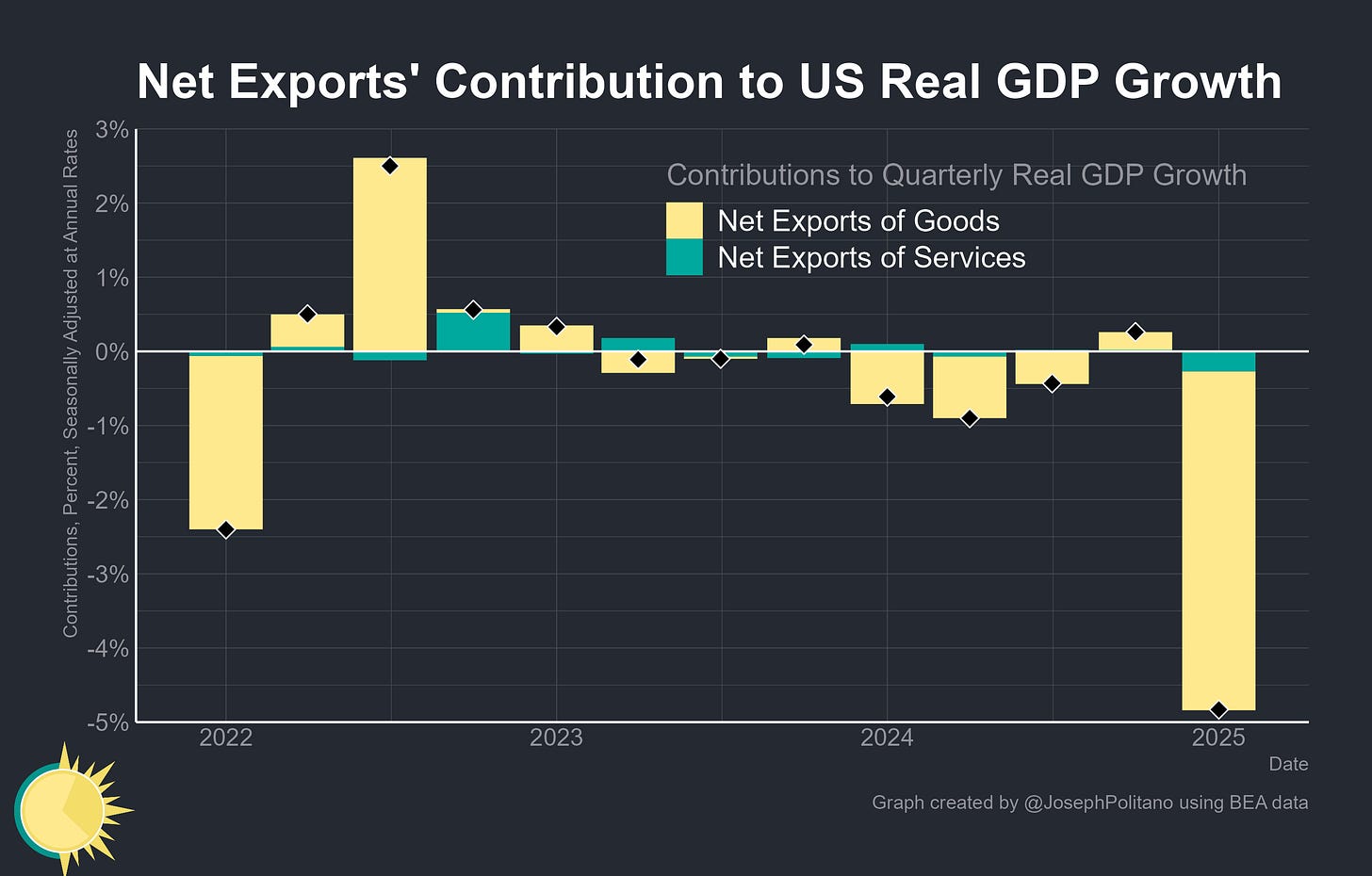

The US economy shrank at the beginning of 2025 for the first time since the recession scares of early 2022—GDP contracted at a 0.3% annualized rate, a major downgrade from the 2.4% growth registered at the end of last year. The culprit was the massive economic drag from trade wars, with companies and consumers forgoing business-as-usual to stock up on foreign goods before Trump’s massive tariffs took effect. The trade deficit expanded to record highs in Q1, with investment jumping as American businesses stored or installed their imported goods.

In fact, the trade deficit expanded at such a rapid pace that net exports notched their largest quarterly decline since records began in 1947. Now, it’s important to clarify that this import surge does not itself shrink the economy—GDP is an estimate of domestic production, and is not affected by purchases from abroad. Yet domestic production is difficult to measure directly, so GDP is estimated by summing consumption, investment, government output, and exports while subtracting imports only to prevent double-counting. Thus, consumers rushing out to buy foreign-made clothes will show up as an increase in imports (a negative “contribution” to GDP) and an increase in consumption (an equal-and-opposite positive “contribution” to GDP) and have no net effect on economic growth.

In this case, however, the surge in imports primarily manifested as a surge in business inventories—it was corporations, not consumers, doing most of the stockpiling. The positive contribution from inventory growth was the highest since late 2021, “offsetting” a bit less than half the jump in the trade deficit. Fixed investment of foreign equipment also helped significantly “offset” the increase in imports at the start of this year.

Yet it’s also important to say that the costs and uncertainty of trade policy chaos can have real negative growth effects. If a construction company rushed to buy a bunch of wood from Canada ahead of tariffs, that would show up as an increase in imports and an increase in inventories which cancel each other out. But if that company slowed down construction so it could afford to stockpile inputs, that would show up as a hidden drag on GDP in the form of lower investment. In other words, tariff front-running can indirectly slow the economy, and that’s exactly what we saw at the start of this year.

Breaking Down the Import Surge

Real imports of goods shot up to a record high at the start of 2025, rising nearly 11% from the end of 2024. The only recent trade shifts of a similar scale are the COVID pandemic and the 2008 recession, yet while those events caused unprecedented contractions in trade, the threat of tariffs has done the exact inverse and caused trade to surge at a speed not seen in 50 years.

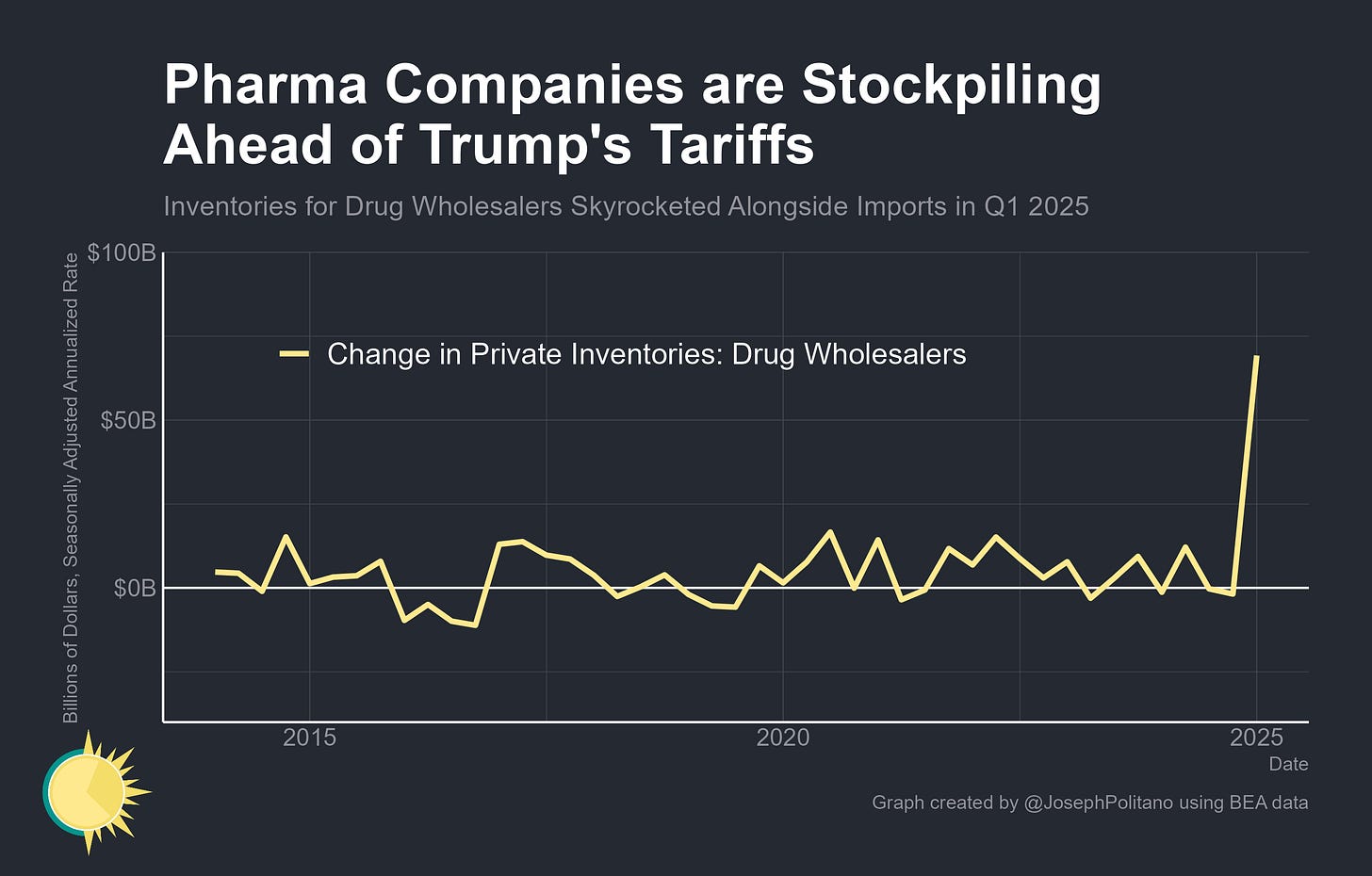

Computers & pharmaceuticals were the two sectors behind the vast majority of that record import surge—outside those industries, the jump in imports was noticeable but not record-breaking. Pharmaceuticals, an industry Trump has long promised to hit with tariffs on but has exempted from nearly all trade policy actions so far, saw their real imports jump 60% from their previous record high. On the other hand, computers were not specifically targeted by Trump in the same way as pharmaceuticals during Q1, but they were heavily dependent on a Chinese & broader East-Asian supply chain that risked heavy disruption from tariffs. Real imports of laptops, desktops, and other computers thus rose by more than 50% in Q1 2025 as companies tried to prep for disruptions to their complex supply chains. Where did all those drugs and electronics go?

The pharmaceuticals were mostly stockpiled by medical companies—drug wholesalers’ inventories rose by the highest amount ever recorded, beating the previous record-high by a factor of 4. In fact, the rise in pharmaceutical inventories was so large that it was single-handedly responsible for nearly 40% of the total increase in inventories across the entire US economy. This is downstream of both genuine stockpiling of the range of medicines made only outside America and a rush by drug multinationals who use transfer pricing schemes to book as much profit as possible in Ireland, Switzerland, Singapore, and other low-tax jurisdictions before the tariffs kick in. This record pharmaceutical stockpiling is also far from over, as preliminary data from the EU countries responsible for most US drug imports shows even larger increases on the near horizon.

By contrast, the record-high imports of computers were mostly driven by rising investment at AI labs and other tech companies, not by business inventory growth or consumer electronics spending. Fixed investment in computers & peripheral equipment rose 21% in Q1 to a new record high as firms continue investing more and more in computing capabilities. In fact, computers & broader information processing equipment were responsible for more than 70% of the increase in total fixed investment this quarter. This import surge is also unlikely to slow anytime soon—even though Trump has promised tariffs on computers, semiconductors, and electronics at some indeterminate point in the future, at the moment most computers used for AI training come from either Taiwan or Mexico and remain totally exempt from tariffs.

The Other Bits of GDP

Outside of the rapid shifts in trade itself, consumption growth also changed considerably at the start of this year. Spending on motor vehicles and parts had their worst quarter since mid-2021, mostly as a come-down from the rapid growth at the end of 2024. This was one area where tariff front-running was extremely early, with consumers rushing to buy cars before Trump even took office. This led to muted car sales in January/February, only partially offset by the rapid increase in sales after Trump officially announced auto tariffs in March. Meanwhile, spending on pet supplies, toys, cosmetics, clothes, and other miscellaneous non-durables kept growth in that category relatively normal. Finally, services consumption had the smallest contribution to GDP growth in a year and a half thanks to slowdowns in healthcare and food services spending.

DOGE cuts to federal employment and grantmaking also shrank public-sector output in Q1 for the first time since mid-2022, with both major categories of federal activity contracting. Defense output had its worst quarter in years amidst cuts to spending on civilian employees and miscellaneous military supplies, while nondefense output also shrank due to employment cuts. Finally, cuts to federal education and health grants also dragged heavily on state & local activity.

Yet even amidst all of this chaos, “core” American economic growth has held up relatively normally. Real final sales to private domestic purchasers—a mouthful of a term that just represents the sum of private-sector consumption & fixed investment—grew at a standard rate of 3%. These metrics are not wholly untainted by the effects of trade policy (the increase in fixed investment is mostly from tariff-driven computer imports, for example), but provide evidence that the economy has not yet entered a recessionary spiral. Going forward, volatility in overall GDP will be extra high given the wild swings in imports and inventories, so keeping an eye on the health of these “core” metrics will be critical.

Conclusions

This data does not predate all of Trump’s tariffs—taxes on Chinese imports were already 20% by the end of Q1, tariffs on non-USMCA-compliant imports from Mexico/Canada were 25%, and the steel & aluminum tariffs had also gone into effect—but it does predate the entirety of the massive April 2nd tariff hikes. In other words, the economic shifts seen in these numbers are mostly from the threat and uncertainty surrounding tariffs, not from the actual tariffs themselves. Trade policy shifts will continue dominating the US economy in the short run, and the tariffs will serve as an even larger drag on growth as they start to truly bite.

Great analysis. Why didn't the increase in drug inventories mostly cancel out the rise in drug imports? And do most computer-related imports count towards higher inventory, investment, or consumption?

Great article. Seems like pharma was the only industry taking Trump tariff threats at face value but I have to imagine that’s because their procurement folks understand the grave seriousness of a disruption to their supply chain vs no toys on the shelves. Likewise, it seems like consumers weren’t taking Trump serious enough so will be interesting if there’s any way to get the same kind of analysis of just April.