The Curious Case of the Missing Artists

A Parable About how Recessions Permanently Damage Industries at the Expense of Low Income Workers

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

At the onset of COVID-19, Broadway shows closed their doors for the longest time in history. Production halted on virtually all TV and movie sets as Hollywood ground to a halt. Movie theatres turned away customers and box office revenues tanked for major motion pictures. Even Netflix, YouTube, and the other digital titans found themselves struggling to create new content in the face of the pandemic. Amusement parks were shut down and casinos remained inaccessible. Employment in the arts, entertainment, and recreation sector dropped by more than half from 2.5 million in January 2020 to 1.2 million in April.

This story isn’t about that recession. It is about the prior recession, the Great Recession, and—in a way—all recessions.

During the Great Recession, firms in the arts and entertainment sector were heavily squeezed by the drop in spending. The result was the same as it was throughout the economy—price cuts, wage stagnation, investment cutbacks, and mass layoffs. The secular trends that had pushed arts and entertainment to become an increasingly large subset of America’s economy were slowed dramatically or halted entirely. Those at the bottom rungs of the industry bore the brunt of the damage. A generation of young artists were turned away from the profession by scarce opportunities and low wages. This is the story of the missing artists—and how we can keep them this time.

Show Business

Over the last 30 years, arts and entertainment has drastically increased its share of total US employment as part of the country’s long term shift from manufacturing to services and the interpersonal economy. The result has been steady growth in jobs as producers and directors, film and video editors, and various designers. The largest interruption in this trend is happening now, as the entertainment industry bears a disproportionate share of the economic damage from COVID-19.

The road before COVID hasn’t always been smooth, either. Take museums and other historical sites—among the most clear-cut “cultural” industries where employment subsector data is available. Its share of total employment has more than climbed dramatically since 1990, but the recessions of 2001 and 2008 put noticeable, permanent dents in the industry’s growth.

This is representative of employment throughout the arts, and indeed almost all growing industries in the United States. In the hypothetical higher-income, higher-employment economy that would have occurred in the absence of the recessions not only would a higher amount of people be working in museums, but a higher percentage of jobs would be in museums as well. Instead, job opportunities in the arts dried up and college students shifted out of majors in the arts and humanities. A half-generation that would have studied English, history, or the performing arts was instead locked out of the industry.

As a leisure activity, consumer spending on the arts is extremely pro-cyclical. Consumers spend the most during good economic times and cut back dramatically during recessions. Take Broadway—after the 2008 recession the industry was forced to cut ticket prices drastically in order to preserve attendance. The result was a precipitous drop in gross revenue compared to expectations that took until 2013 to recover from. Keep in mind that Broadway, with its big budgets, prestigious shows, and prime location, was among the live entertainment areas least-affected by the recession. Smaller, not-for-profit theatres saw a more than 25% reduction in their earned income between 2007 and 2009.

Love’s Labor’s Lost

Workers in the arts and entertainment suffered the most from the slowdown. General employees in the industry are no more likely to be represented by a union than the average private-sector worker, but upper-level actors, musicians, and other performers have strong union representation. Union actions, however, are highly responsive to the state of the business cycle—in general, they are emboldened and strengthened by tight labor markets.

The Screen Actor’s Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) commercial actors strike occurred just before the 2001 recession, and the infamous Writers Guild of America (WGA) strike occurred just before the start of the Great Recession. When unemployment started rising unions lost leverage—it took nearly a decade of employment growth before the next strike, a lengthy dispute between SAG-AFTRA and various video game publishers surrounding the rights and pay of video game voice actors. Today’s tightening labor market has also afforded labor organizations new strength—a strike by the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) was narrowly averted after studios signed a deal guaranteeing higher wages and better working conditions.

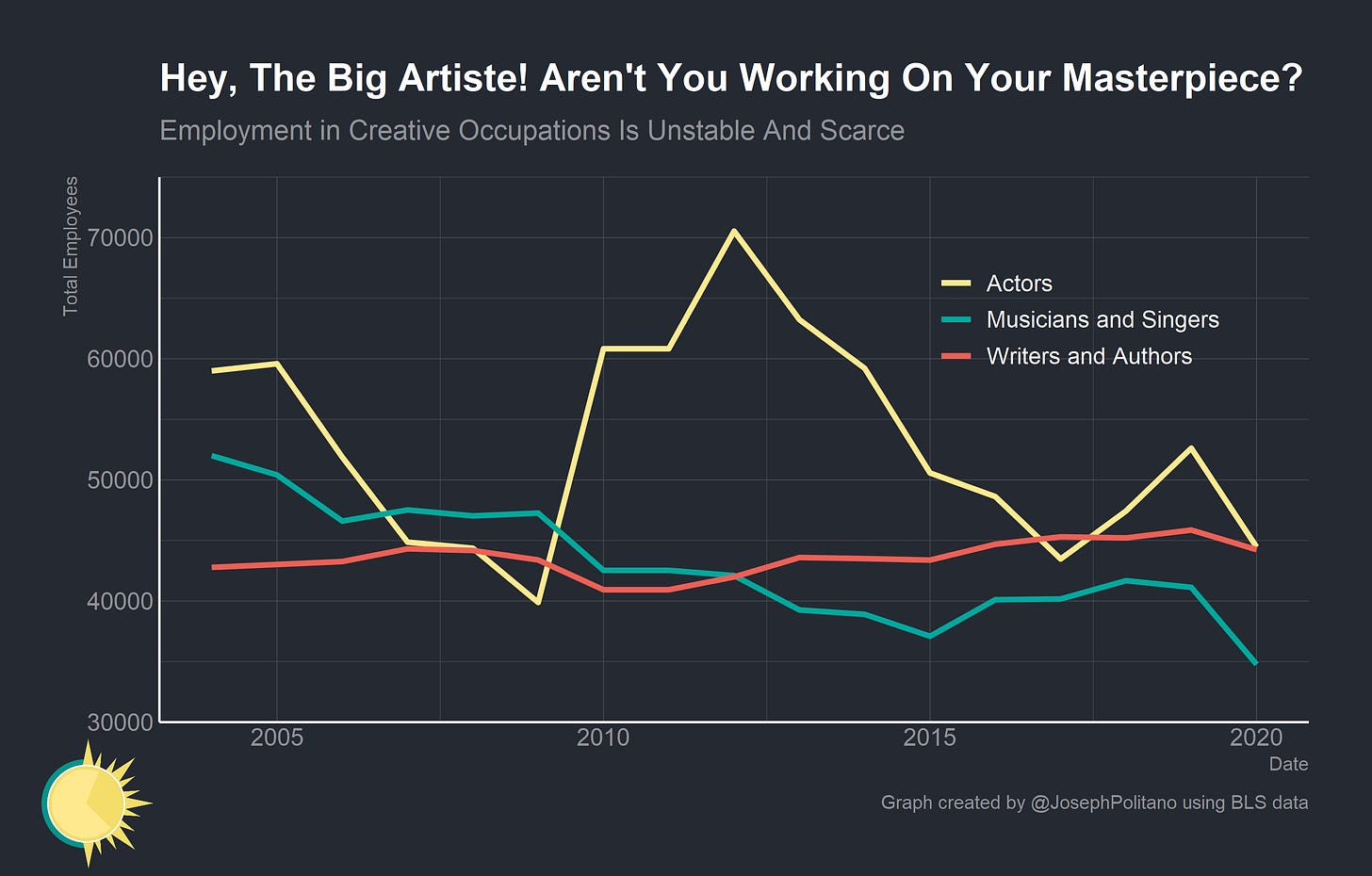

Employment in artistic occupations is generally unstable and has been relatively weak for decades. The general decline in employment for musicians and singers was only accelerated by the recession and only reversed after the labor market began improving in the latter half of the 2010s. The smaller dip in authors and writers’ employment took until 2013 to recover from—though actors’ employment remains uniquely unstable.

It should be noted that the apparent instability is partly due to extreme inequality within the industry and partly due to classification and data issues. To the first point, about 60% of actors have an annual wage estimated at under $30,000 and the industry is more unequal than the already-unequal aggregate US labor market. To the second point, the Occupational Employment and Wages Survey (OEWS) does not collect data for the self-employed and Census Public Use Microdata did not contain good breakdowns of the self-employed until recently. What we do know is that between 25-30% of actors are self-employed, and many may transition regularly between self-employment and hourly employment.

Taking a look at median hourly wages is more illustrative of the damage wrought by the Great Recession. Wage growth for writers and authors practically stopped from 2008-2012, and wage growth for musicians and singers didn’t jumpstart again until 2015. Wages for actors were much more unstable, reflecting the aforementioned inequality, variance in employment, and data collection issues.

Annual wages for editors, producers, directors, and other special effects artists showed more robust growth throughout the recession, but still suffered. In particular, wages for producers and directors stalled precipitously and wages for special effects artists suffered slightly. At some level these positions were supported by the general increase in digital video content and computer generated imagery, but at another level these were simply higher-income specialized positions that were not disproportionately likely to experience layoffs or wage cuts.

The employees most disproportionately affected by the recession were those with no direct creative work but nonetheless dependent on the success of the entertainment industry. Amusement and recreation attendants, alongside similar positions like lobby attendants, ushers, and ticket-takers, make up far and away the single largest occupation within the arts. The nearly 350,000 amusement and recreation attendants dwarf the less than 150,000 total people employed as musicians, actors, and writers combined.

They were also the primary victims of the Great Recession within the entertainment industry. Employment growth for attendants was halted in its tracks, and it took until 2015 for job growth to resume. In 2020 these workers were also among the most likely to be laid off—total employment for all entertainment attendants and related workers dropped from 628,000 in 2019 to 450,000 in 2020.

Wage growth for attendants, ushers, and ticket-takers also completely halted by 2010 and did not restart until 2015. When firms experienced cutbacks in revenue as a result of the recession, attendants and other related workers were among the first to be laid off and the last to be re-hired. Layoffs were prevalent and there was an omnipresent drop in hiring. Making do with fewer attendants was simply easier for firms than making do without the workers who were directly responsible for artistic production.

Conclusions

When recessions happen, it is workers who suffer the most. And when workers suffer, it is those least able to bear it—the lowest income, the least-unionized—that suffer the most. Centering these workers in measuring, prognosticating, and fighting recessions will make for better analyses and a better economy.

In 2021 we are again threatened by a generation of missing artists. This time it is not only the generalized downturn in output that is damaging the industry, but the specifics of the pandemic that have disproportionately affected the industry. Restrictions on consumption at theatres, amusement parks, and casinos alongside a fall in on-set and in-office production have left the entertainment world in a precarious position.

This time, however, we have a chance to bring the artists, musicians, and writers, back and ensure that future workers have ample opportunities within the creative arts. We have a chance to bring back the essential but underpaid workers that are overlooked in discussions of labor market and industry dynamics. From a macro perspective it’s going to mean using monetary and fiscal policy to push for full employment while ensuring that nominal incomes do not dip below trend like after 2008. From a micro perspective it’s going to mean rebuilding unionized workforces and fighting for fairer economic institutions.

If we do so, we’ll be building a richer world both economically and culturally. The tragedy of 2008 wasn’t just that there were missing actors and singers, but missing nurses, teachers, engineers, construction workers, and office workers. Just like with art, the economy is simply about the ways we enrich each other and ourselves. The tragedy of 2008 was that the recession immiserated everyone and that the downturn in nominal output itself was completely preventable. The funny thing about tragedies though is that we keep telling them in the hopes that one day we will learn the lesson and the story can finally end happily.

If you liked this post, consider subscribing to get free economics news and analysis delivered to your inbox every Saturday! Leave a comment below to participate in the discussion or share this post to others who may find it useful!

Best analysis I have seen today, thank you!