The Death of NYC Congestion Pricing

And What is Says About the Institutional Problems in American Cities & Infrastructure

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 42,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

New York City and its surrounding suburbs make up the largest urban economic cluster on planet Earth. 2.4 million people work in the 23 square miles of land that make up the borough of Manhattan, and collectively they produce $886B in economic output, a nominal sum larger than Vietnam and Pakistan’s GDP combined. Most of those workers take the subway.

Globally, that is nothing notable—in most urban cores a majority of workers take public transportation for work and daily activities. Increasing the density of jobs, hospitals, restaurants, homes, schools, and more is key to the agglomeration effects that make cities such economic powerhouses, and as density grows mass transit becomes essential since it can far surpass the maximum throughput capacity of even the largest roadways.

Yet in the US, it’s extremely unusual for most workers to take public transportation—in 2022 only about 3.1% of Americans took trains or buses to their jobs and about 45% of those transit commuters lived in the Greater New York area. Chicago, Boston, DC, LA, San Francisco, and Philadelphia are the only other major American cities where a substantial number of workers take transit, and in none of them is the transit mode share above 25%. New Yorkers’ inflated sense of self-importance is one of the longest-running jokes about the city, but it’s true that in this way the Big Apple is fundamentally America’s only major city. Thus New York’s public transit policy is fundamentally America’s public transit policy—and NYC’s urban development is in many ways America’s urban development.

That’s why it was so important when earlier this month, New York State Governor Kathy Hochul announced that America’s first congestion pricing scheme would be “indefinitely paused”. The policy would have charged vehicles for entering the perpetually gridlocked streets of Lower Manhattan, using the money raised to then fund many of the city’s transit projects—and it was slated to officially begin operating less than 30 days from the announcement. In the short term, the flip-flop will be extremely costly for the city and state, but more broadly the cancellation and the dynamics that led up to it are emblematic of many of the problems holding back American cities & infrastructure.

Why Tax Congestion?

In one sense, the congestion pricing scheme is a radical new experiment in American transportation policy. Cars compete for scarce urban road space with more efficient modes of transportation like buses, emit large amounts of noxious chemicals and particulate matter from tailpipes and tires, are the leading cause of death for Americans under 55, and in large quantities become disruptively loud for workers and residents. Lower Manhattan is among the few places in America where substantial transit alternatives to driving exist, so a congestion tax should induce mode shifts away from cars and toward the subway—to the benefit of the local and global climate. Wealthier residents are more likely to drive and poorer residents more likely to take transit, so congestion pricing serves redistributive purposes as well. New York’s scheme promised to be a pioneering first for the nation, a pilot project that if successful could be copied in cities throughout the US.

Yet in another sense, the plan should be entirely unremarkable. Congestion pricing has existed in some form throughout cities across the world for 50 years, and is fundamentally just a fancy version of the normal tolling systems that are common on bridges, tunnels, and other roadways. People who drove into Lower Manhattan were already “paying” for the privilege to do so, just with the time and gasoline lost to bumper-to-bumper traffic rather than in hard cash. As with any heavily overcrowded bridge or highway, mispricing was causing economic inefficiency—charging for entry would allow priority vehicles to get where they’re going faster, incentivize better use of existing roadways, and open up a funding stream that could be used to expand beyond current infrastructure constraints. Economists would recommend some form of congestion pricing just for the benefits to road users alone. Plus, once implemented, these schemes are usually popular among city residents—public opinion of London’s congestion charge rose nearly 20 percentage points after implementation and Stockholm’s congestion tax was approved by voters after a 7-month trial period.

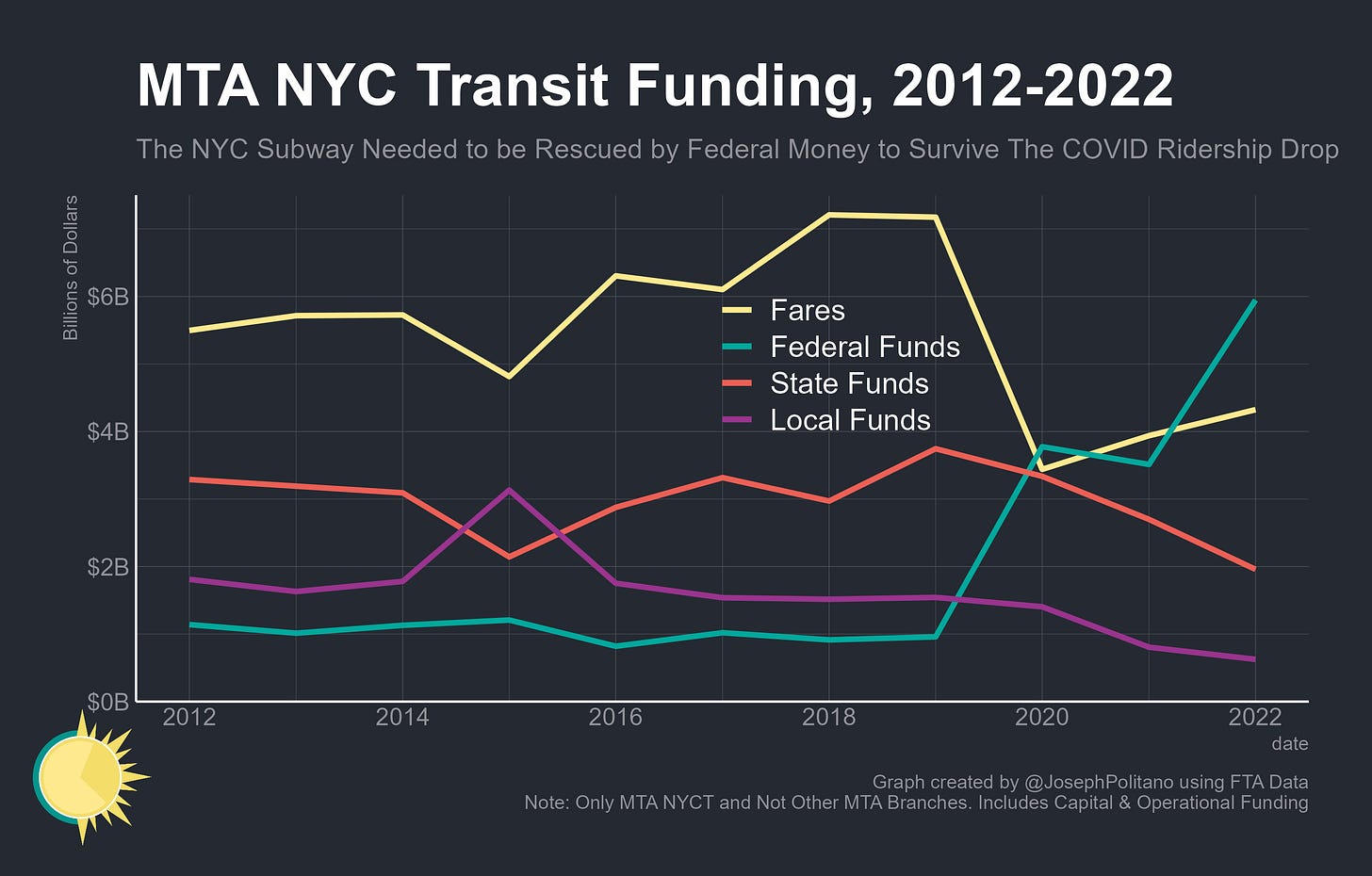

In a more practical sense, New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) needed new post-COVID funding streams. After ridership (understandably) cratered during the early pandemic, the system had to be bailed out by federal cash infusions from the CARES Act and American Rescue Plan alongside nearly $3B borrowed from the Federal Reserve. Remote work enabled shifts out of New York’s expensive real estate market and into the city’s suburbs and other metro areas, making it even more difficult for city bus & rail ridership to recover.

Yet while transit ridership continues to struggle, MTA bridge & tunnel toll revenue has more than completely recovered to pre-COVID levels. People were increasingly driving into the city and underutilizing transit infrastructure—thus congestion pricing, while initially envisioned for a pre-pandemic world, rapidly became a necessary part of plans for a post-COVID recovery. Taxing traffic, with all its negative externalities, was certainly much more politically palatable and economically beneficial than attempting to raise payroll taxes further, which would have strained New York’s already-slow post-COVID jobs recovery. Plus, the incidence of congestion taxes would also fall more on tourists and residents of New Jersey/Connecticut, helping to recapture some of the economic value lost to the suburbs as a result of remote work. The policy should have been an easy win for the city.

The Death of Congestion Pricing

Yet just before implementation, congestion pricing was indefinitely paused at a press conference framed around inflation and cost of living concerns, highlighting how much the tax side of the scheme loomed large in voters’ minds. That makes sense for drivers from Bergen County in northern New Jersey, for whom the system was (financially) all cost and no benefit—they would pay to enter downtown, but the revenue collected would all go to transit investments outside their county, and their primary benefit would thus only be experiencing less traffic when driving through Manhattan. But Governor Hochul does not represent New Jerseyans, and for New Yorkers (especially the 55% of city households who don’t own a car), the tradeoff was supposed to be clearer—impose costs on a small subset of drivers to deliver benefits in the form of transit investments that would serve the majority of people. Those benefits, however, felt relatively small to many city and state residents.

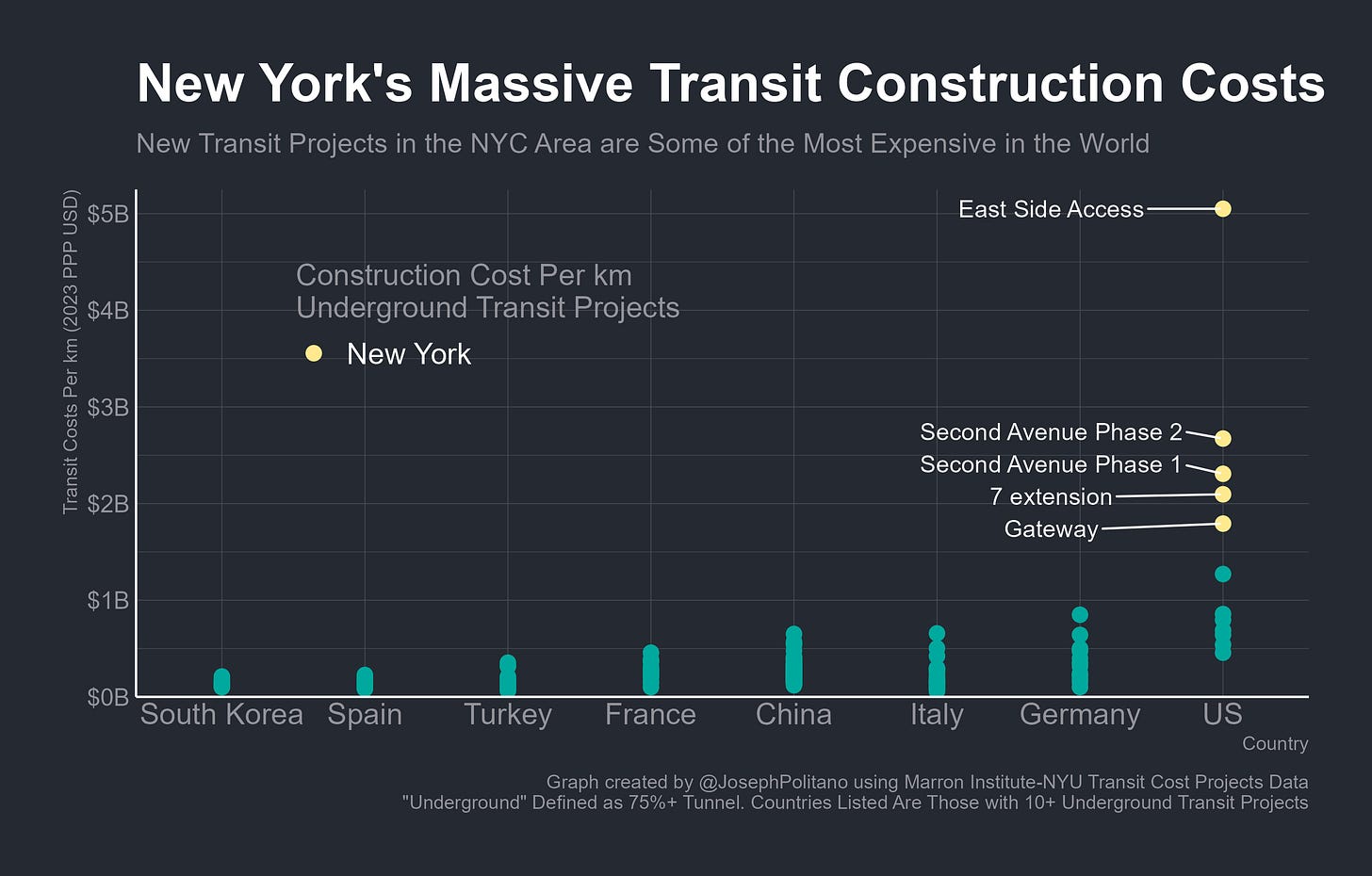

A lot of congestion-pricing criticism posits that the MTA already has “enough money” and just needs to spend it better. In many ways, they have a great point—the MTA has a total operating budget of $19B, an amount larger than many states, plus a capital investment budget of roughly $11B a year, and they build relatively little with it. High costs for new public transportation infrastructure is an America-wide problem but is at its absolute worst within the city—of the 5 most expensive projects tracked by the NYU-Marron Institute Transit Costs Project, 4 are in New York City. It would be great if New York could build transit infrastructure at something approaching the cost-per-mile of other dense urban areas in much of Asia, continental Europe, or South America, but even reaching the still-boondoggle levels of the Bay Area Rapid Transit extension to San Jose would be a massive improvement. Even as billions are spent, construction takes much longer to complete in NYC—in the 15 years it took to complete the East Side Access project, the Delhi Metro in India added 7 new lines and increased ridership by more than 1B trips per year.

These MTA projects are still worthwhile—cost-per-rider projections for NYC transit actually tend to be relatively benign (by the very low standards of American transit) because the city’s expensive projects are still moving through some of the densest neighborhoods in the country and link to an extremely comprehensive existing network. But high costs force New Yorkers to settle for a much lower-quality, lower-capacity system. Take the Interborough Express, a planned orbital transit line between Brooklyn and Queens designed to improve access in transit deserts throughout the city and connect with 17 existing subway lines. The line will be lower capacity light rail, not the kind of heavy rail that the subway runs on, will mix with aboveground street traffic throughout some subsections of Queens, be built mostly by repurposing preexisting freight right-of-way, and is still projected to cost $5.5B. The fact that with billions of dollars in new revenue the MTA could only promise marginal expansions rather than transformative system-changing investments reduced the perceived benefits of the congestion pricing scheme—allowing narrow dedicated opposition among a portion of suburban drivers to topple the program.

Yet I think congestion pricing opponents miss how their victory is emblematic of—and exacerbating—the city’s transit cost problems. The Governor is turning the MTA into a nightmare customer and a horrible coworker here, as the cancellation of congestion pricing jeopardizes key funding and matching federal dollars for a suite of construction projects at the 11th hour. The MTA’s CFO was forced to announce that the agency will now need to “reorganize the [2020-2024 Capital] Program to prioritize the most basic and urgent needs” because it “cannot award contracts that do not have a committed, identified funding source.” That means tens of billions of dollars in investments could be shelved, including Phase II of the Second Avenue Subway, the Metro-North Penn Station Access expansions, a host of station upgrades, and much more. Contractors who work with the MTA on these projects already charge a premium for having to manage the substantial risk that construction is delayed or canceled—introducing “the Governor might suddenly decide your job is over” as another risk to worry about will just increase those cost premiums, thin the pool of companies who are capable of working with the MTA, and reward the politically savvy.

The fact that infrastructure plans can go through years of study, environmental review, public consultation, pilot projects, revisions, lawsuits, construction, delays, and more only to then be shelved days before final implementation is a large part of why public works are so expensive in the first place. The number of veto points for American infrastructure is extremely high—even one “no” across from any number of officials throughout construction can stop a project dead—and that veto power makes it easy to extract money and concessions from projects. Pick more costly construction methods to minimize surface disruption, reduce daily construction time to leave existing traffic unimpeded, move infrastructure to suboptimal locations to appease powerful voting constituencies, expand stations to meet interagency demands for back office space, and in the absolute worst cases just use discretionary powers to do quid-pro-quo corruption. Also, imagine if you were among the hundreds of state, local, and federal civil servants who worked on any part of the congestion pricing or MTA capital investment plans—would you want to remain at your job after having years of work tossed aside at the last minute? The hollowing out of institutional capacity within transportation agencies is a serious driver of cost problems, with planning becoming a bespoke project-by-project activity heavily dependent on expensive outside consultants rather than a regular in-house activity.

As a more practical matter, hundreds of millions were already (over)spent on congestion pricing between years of studies, protracted legal battles, construction of physical infrastructure, contracts for implementation, and much more—all that money is wasted by pulling the plug at the last possible second. The cancellation of congestion pricing without an alternative funding stream will hurt the MTA’s credit rating, increase its debt-servicing expenses, and functionally impose even more costs on New Yorkers. Before the congestion pricing cancellation, the MTA had actually made some rare positive efforts to control infrastructure construction costs, including saving $1.3B in Phase II of the Second Avenue Subway project, yet instead of building on that the Governor has decided to throw the entire infrastructure program into jeopardy.

Talking Broadly About American Public Transit

America invests little into public transportation infrastructure by the standards of similarly-wealthy European and Asian countries (or even relative to Canada and Mexico). Pre-pandemic, it was normal for urban mass transit to receive only 6-9% of all state and local land transportation spending, and for bus and train passenger terminals to receive roughly another 3-5%. However, relative spending on both items has cratered post-COVID, with the share of construction spending going to mass transit falling to the lowest levels in a decade this year. Even when these investments are made, American cities struggle to make the best of new infrastructure.

Public transit is a network system that depends on scale to be successful—a two-line metro is more than twice as valuable as a 1-line metro, and a metro that goes between dense downtown neighborhoods is much more valuable than one that meanders through sprawly suburbs. A large part of why American transit infrastructure projects fail is because even when built they are placed in the middle of nowhere or are undercut by local governments that prevent the necessary complementary neighborhood housing and commercial developments. Take the new Silver Line Extension of Washington DC’s Metro—stations like Loudoun Gateway are currently transit to nowhere, situated near a field and highway interchange just outside Dulles Airport, and thus serve only a couple hundred riders per day. Meanwhile, existing stations that were coupled with substantial housing development, like Navy Yard-Ballpark, had some of the fastest-growing ridership of the entire system pre-COVID. The immediate vicinity of the North Berkeley BART stop in California is surrounded on all sides by parking lots, and thus the station currently sees only about 1,700 riders per weekday. A redevelopment is finally planned for the land surrounding the station, but this will still likely bring less than 750 new homes to the area.

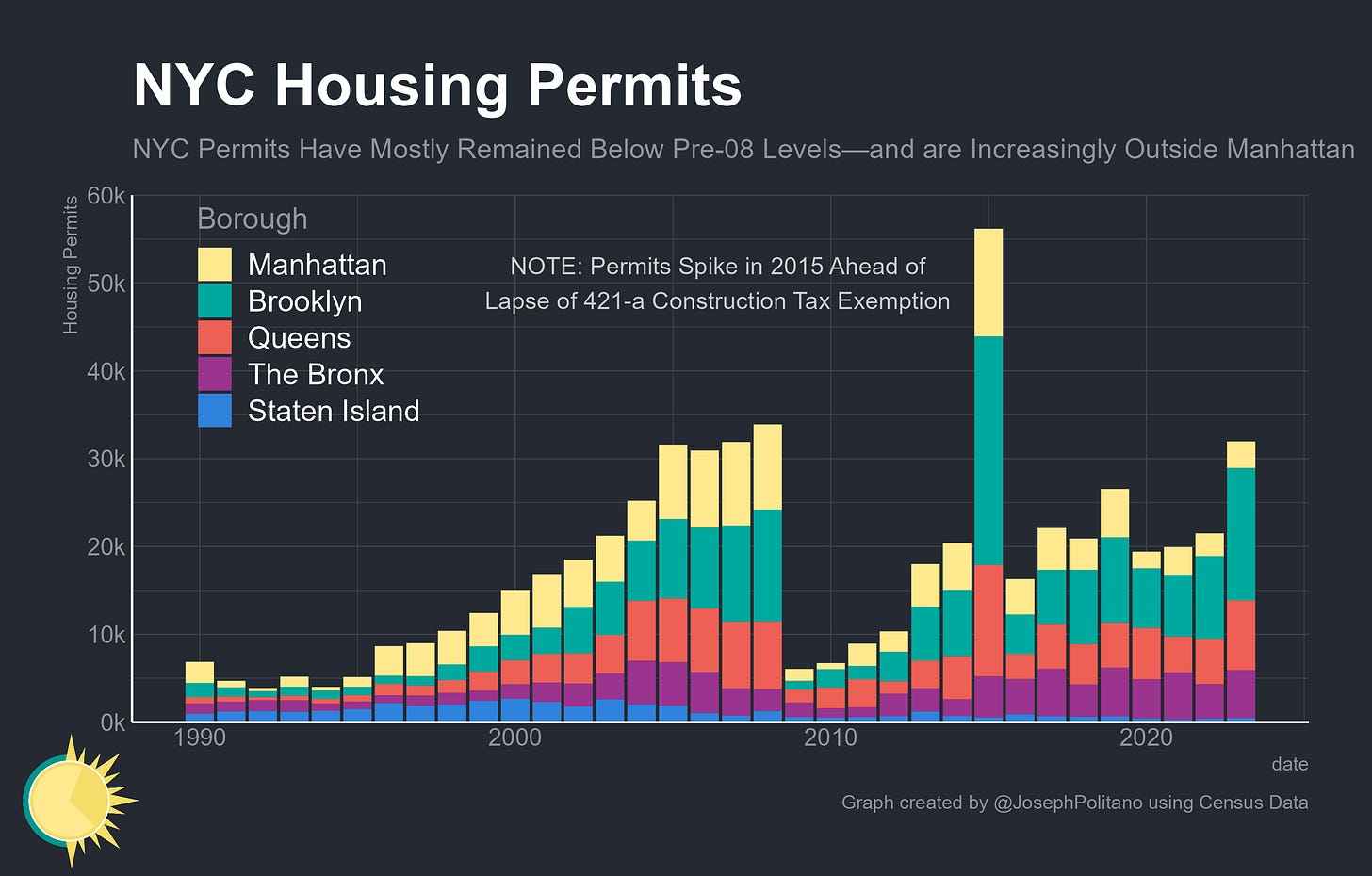

In New York, the high cost of the East Side Access project would be more palatable if more progress had been made on Sunnyside Yard—a plan to build housing and a new station on top of an existing train yard like in the Hudson Yards redevelopment—and if the proposed number of housing units hadn’t already been scaled back. More broadly, over the last 6 years more housing has been built across the Harlem River in the Bronx and across the Hudson River in Jersey City than in the extremely transit-accessible and high-demand neighborhoods of Manhattan. The city’s housing policies are, among a myriad of other issues, making the MTA less effective—had the city built more in the 2010s, COVID outmigration wouldn’t have been so severe and the MTA’s network could draw from a much stronger ridership base. The defeat of reform efforts like Governor Hochul’s housing compact, which would have allowed for more dense housing construction around transit stations, are entrenching this extremely flawed status quo.

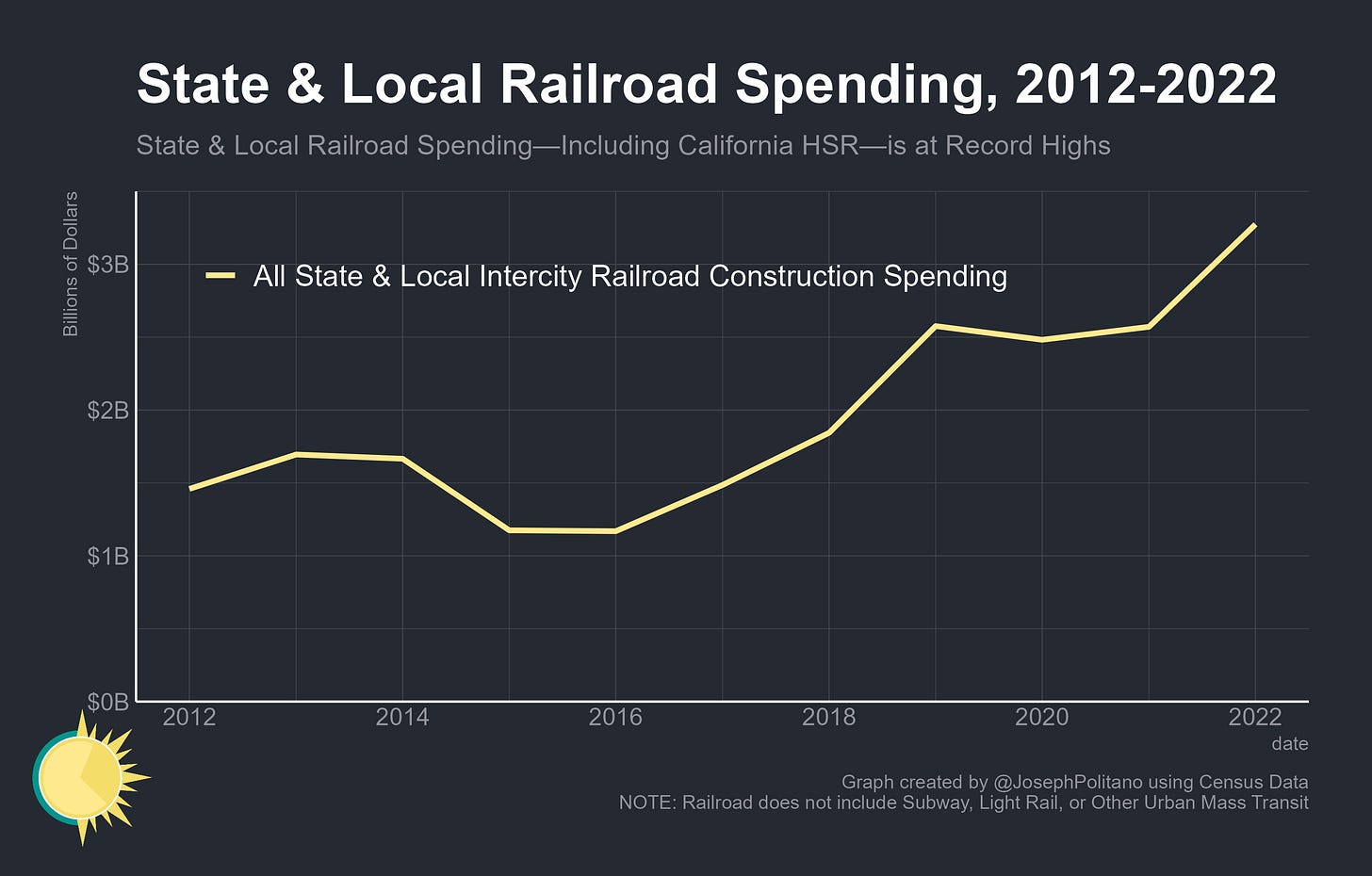

These cost and ineffectiveness problems are also mirrored in another infrastructure area where spending is actually increasing—intercity rail. State and local spending on rail construction has hit a new record high post-COVID, rising above $3B a year for the first time. The project most emblematic of this construction surge is California High Speed Rail, which aimed to be America’s first modern HSR system but has hit a long series of snags since it was first authorized by voters in 2008. Slow land acquisition, lengthy environmental review, and repeated legal battles continually delayed the project and increased its costs. Along with other issues, this has meant the line is only scheduled to start operation on a segment between Bakersfield and Merced in the early 2030s, and the full price to connect San Francisco to LA is likely to exceed $100B.

At current cost estimates, the Bakersfield-Merced initial operating segment is already expensive by global standards and the SF-LA line would be among the most expensive high-speed rail projects in history. This is with generous assumptions for CAHSR—especially the assumption there won’t be further cost increases when construction starts on more difficult rail segments—and still the only lines with similar price profiles are those built largely underground or those in the UK where cost inflation is often even worse. Even accepting that the initial operating segment can open on schedule in the 2030s, there is still no timeline for the project to connect to either San Francisco or Los Angeles, and another source of funding will need to be found before construction to those cities can continue. While not complete transit-to-nowhere, the fact that the highest-speed train in the Americas will be only shuttling people between some of California’s smaller car-dependent cities for years is emblematic of the struggles of US transportation planning. Good infrastructure has large diffuse benefits and small narrow costs, but with enough twisting you can make the benefits smaller and the costs larger.

Conclusions

The practical future of the congestion pricing scheme remains up in the air. There are inevitable legal battles that will have to be settled regarding Hochul’s attempt to pause the project, and the appetite for a payroll tax increase seems to be low, leading to talk of raiding the state’s general fund or issuing more debt as a stop-gap until another source of workable revenue can be found. Uncertainty is extremely high, but congestion pricing is not completely buried just yet and the lack of viable alternatives may push the Governor’s Mansion to eventually revive the scheme. For New York, a permanent killing of congestion pricing would help solidify the state’s position as a shrinking share of American jobs, residents, and GDP in the post-COVID world.

These all still might just seem like local political problems, especially if you live outside NYC or are among the vast majority of Americans who aren’t reliant on public transit infrastructure. However, many of the issues facing urban public transportation plague all forms of US infrastructure spending. Real per-capita investment in all mass transit (including airports) has been stagnant for 20 years—but real per-capita investment in highways & streets is also stuck at pre-WWII levels. Cost-per-mile for US highway construction has skyrocketed over time, especially in wealthy areas with stronger local opposition, America just more readily pays those higher costs rather than the higher cost for transit infrastructure—which is why it is necessary to get cost problems under control rather than just abandon the idea of transit infrastructure entirely.

American transportation agencies have a notable reluctance to adopt best practices from abroad, yet even within the US there are valuable success stories to learn from. Los Angeles is the city most synonymous with American highway urbanism, but LA Metro is currently engaged in one of the most transformative transit expansion projects in modern American history for a high-but-not-ludicrous price tag. Meanwhile, DC’s Metro has shuffled through a series of operational reforms under new leadership that have dramatically improved ridership for a system that was extremely at risk given how many city residents now work remotely. The death of congestion pricing was among the largest setbacks for American urban infrastructure since the start of the pandemic, but it’s still necessary and possible for US cities to expand and improve their transportation networks.

The funny thing about transit in LA (even the aside that it’s symbolic with highway urbanism) is that it has a transit network that’s way above-average by American standards, although obviously below-average by global developed country standards. It’s actually totally possible to live a reasonably pleasant life in central/west LA without owning a car, whereas no such thing is possible in the mid-sized Midwestern city where I grew up.

The Metro still needs to solve a few huge problems with its expansion, though:

- reform land use and parking requirements near metro stations, otherwise you get massive car-oriented buildings or low-density SFH neighborhoods near stations (see the E line, esp. La Cienega and Rancho Park stations).

- Defeat local NIMBYism on spurious CEQA grounds (Beverly hills held up the D line for decades and now Bel-Air is trying to do the same thing with the Sepulveda Pass line)

- public safety on trains and buses - every time a bus driver or passenger is assaulted, the LA times trots out the same nonprofit jabronis that say that the solution is free fares or jobs or whatever.

I’m a little bearish on the prospects for Metro for those reasons, esp. because the mayor doesn’t seem very interested in reforming land use… but I hope I’m wrong.

As a native New Yorker there are so many things going up. Rent, food, gas, etc. Enough is enough already. The Subway's are so unsafe because of panhandling, drug attics in the subway entranceway threatening customers to pay them to go through the turnstile. I have to communicate with my wife daily who is a city worker and make sure she gets to work safely. Ridiculous. Now you want to force people to take the subway system as a means of travel. Don't think so. MTA, Now isn't the time to try charge us for your congestion pricing plan that because you wanted to implement something on credit. Your loss not ours. Why should we pay for your mistakes. Focus on a subway system that doesn't work. A city worker who loves NY and now unfortunately may consider leaving. Focus on strengthening Our law enforcement to gain respect back and make NYC safe and affordable again.