The Last Dove Standing

Bank of Japan Still Believes Inflation is Transitory—And is Holding Out for Stronger Growth

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 20,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Bank of Japan is the last major central bank that still believes inflation is transitory. Or, perhaps more accurately, they hope it isn’t.

Japan has been dealing with extremely low inflation and low nominal growth for decades—consumer prices essentially haven’t moved since the turn of the millennium and Nominal Gross Domestic Product is still sitting only a shade above 1997 levels. Monetary policy has remained too tight for decades despite 0% short-term interest rates—forcing the Bank of Japan (BOJ) to revive “unconventional” monetary policy tools by setting long-term interest rates at low levels through aggressive Yield Curve Control (YCC) policies and making massive purchases of stocks, corporate bonds, and government bonds through Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE). Though these policies have certainly helped, they still weren’t enough—real output and wage growth have remained persistently low in Japan, leaving the country far short of its potential.

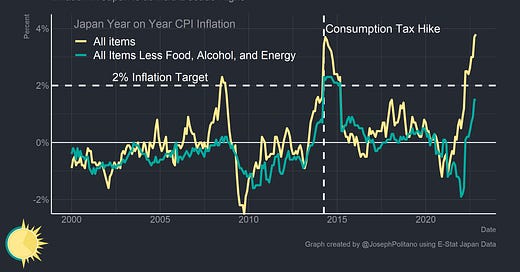

Today, it turns out even Japan cannot avoid the global inflation surge as underlying measures of inflation reach the highest levels in decades, and headline consumer price inflation sits at 3.8%. That’s not high compared to the Euro Area’s 10% and the US’s 7% consumer price inflation, but it still represents more net price increases than Japan saw cumulatively between 1997 and 2020.

Bank of Japan, however, isn’t phased yet—in the December statement on Monetary Policy, they attributed most of the current price increases to “energy, food, and durable goods” and expect these price pressures to decelerate midway through 2023—a familiar echo of how US and European policymakers talked about inflation nearly two years ago. They view the Japanese economy as under “downward pressure stemming from high commodity prices and slowdowns in overseas economies” as the country deals with large increases in food and energy import prices stemming from the war in Ukraine and financial tightening stemming from efforts by foreign central banks to fight inflation abroad.

But in the future, as COVID and supply-side constraints wane, BOJ expects “a virtuous cycle from income to spending” to intensify gradually and for CPI to “accelerate again moderately on the back of improvement in the output gap and rises in medium- to long-term inflation expectations and in wage growth.” In other words, they’re bidding that keeping policy accommodative is the best way to weather the current storm—and might pay dividends by breaking the country out of the low-growth, low-rates liquidity trap it’s been stuck in for decades.

Yield Curve Communication

First, the elephant in the room—at their meeting last week, the BOJ agreed to widen the band for Yield Curve Control (the government bond-buying program they use to target long-term interest rates) by 0.25%, a surprise move that was widely perceived as a hawkish turn. While in the short-run it will likely worsen Japanese financial conditions, the move was arguably more about improving the technical functioning of bond and lending markets rather than explicitly tightening monetary policy. Critically, in the same meeting BOJ expanded its level of Japanese Government Bond (JGB) purchases, framed the move as “maintaining accommodative financial conditions”, and still “expects short- and long-term policy interest rates to remain at their present or lower levels”—not the language of a hawkish pivot.

Still, it is true that Japanese financial conditions are worsening—though this has more to do with tightening at foreign central banks spilling over through the global nature of monetary policy and business cycles. With growth slowing down this year and rapid interest-rate hikes in other major global economies, Japanese firms have seen credit conditions continually deteriorating and reaching levels significantly worse than before the pandemic.

Major Japanese banks tell a similar story—on net, they are no longer loosening credit standards on loans to firms or households. In fact, the share of banks easing lending conditions has reached lows only seen during the 2008 recession and the immediate pre-pandemic slowdown.

This is the bind that BOJ finds itself in—since the country has such a radically different macroeconomic situation than other comparatively large countries it is finding its policy moves out of sync with major central banks. In the short term, free flow of capital means that Japanese firms face a similar degradation in financial conditions as firms in countries with larger inflation problems and more hawkish central banks—BOJ hopes that its dovish efforts will help mitigate the damage to the Japanese economy while hitting the correct exchange rate and level of nominal growth necessary to combat a global slump.

The Inflation Situation

Stepping back a bit, what makes Japan’s inflation situation so different? Well, BOJ is correct that the bulk of Japanese inflation comes from components that are outside the normal purview and influence of monetary policy—Of the 3.81% growth in the CPI over the last year, 1.83% came from food, 1.06% came from energy, and 0.45% came from durable goods—leaving only 0.47% from all other items combined.

They’re also correct to point out that Japanese firms are still struggling under the weight of the pandemic and associated supply-chain issues. Even as production at American automakers has fully recovered, Japanese automakers are still struggling to get output back to pre-pandemic levels amidst ongoing semiconductor shortages.

But the most important difference is just that the bulk of Japanese inflation genuinely does not come from the cyclical components most influenced by aggregate demand and monetary policy—services including housing contributed a meager 0.34% to headline CPI in Japan compared to about 4% in the US. Japanese Nominal Gross Domestic Product (NGDP) remains below pre-pandemic levels, and Japanese NGDP growth sits at a meager 1.2% over the last year—a number consistent with essentially zero cyclical inflation—compared to 9.2% in the US. Knowing that, you can understand why BOJ officials appear sanguine—after being stuck at 0% interest rates for decades, they do not want to risk hard-won economic growth at the first sign of price increases. And today, BOJ is finally seeing positive signs about the path of long-run Japanese economic growth.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Apricitas Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.