The Post-Omicron Employment Bounce

America's Job Market Posted Strong Growth in February, Despite Omicron's Effects

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Last month I wrote that the Omicron variant had a clear, significant negative impact on the labor market in January—keeping employed workers out sick, forcing many establishments to lay people off, and leading to a general reduction in hours worked. With the release of this February’s jobs data, it is clear that the labor market is bouncing back strong—despite some latent effects from the Omicron variant. America added 678,000 jobs in February, with the prime age employment-population ratio (the percent of working age people with a job) jumping by 0.4%. The US is now within 1% of pre-pandemic prime-age employment rates, and a full recovery may be possible by this summer.

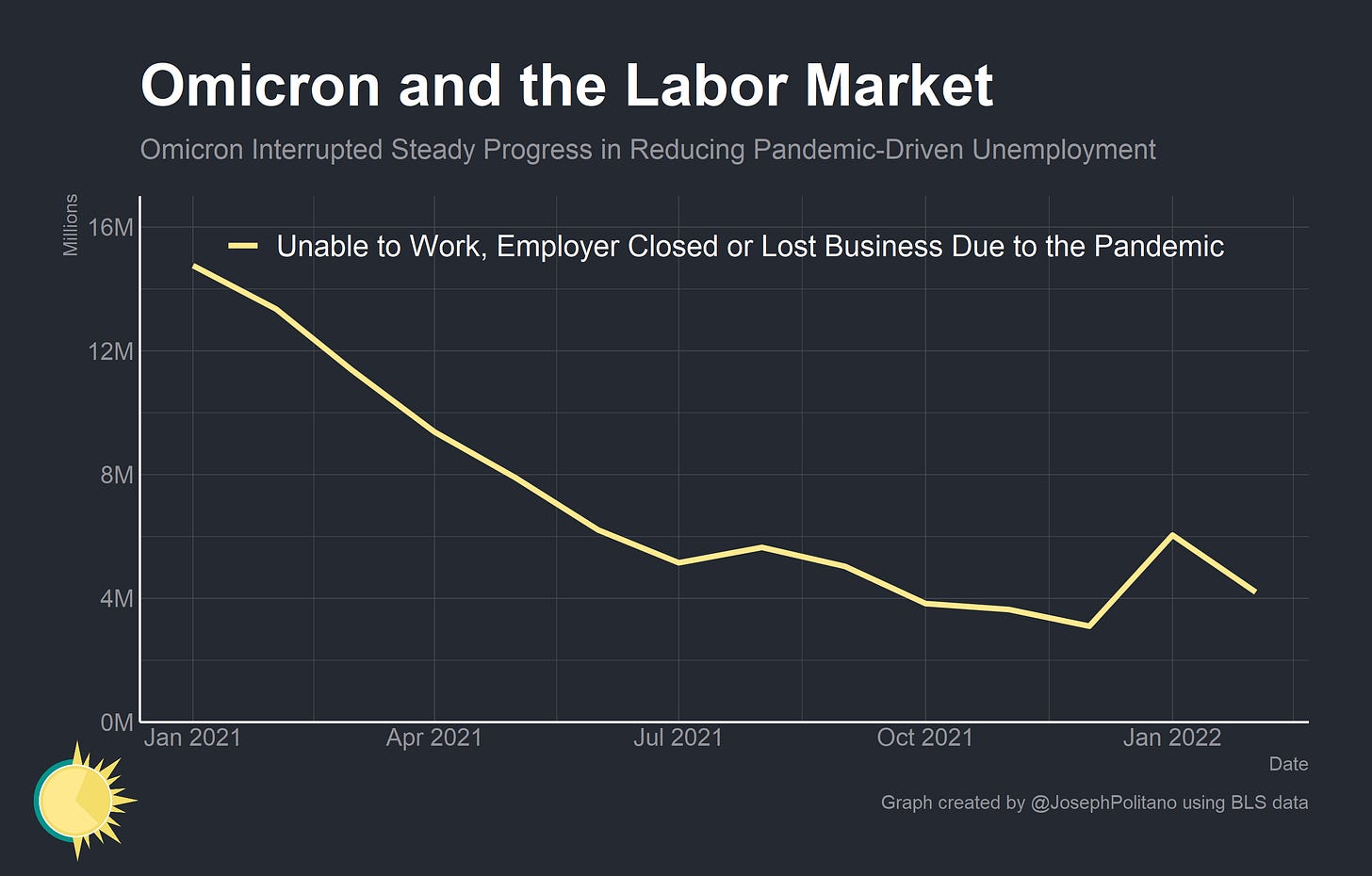

Omicron and the Labor Market

In January, a record number of Americans were out of work sick or had reduced hours due to the Omicron variant. In both cases the number of affected workers was nearly double the previous pandemic highs, with millions of workers out due to illness. Thankfully, February saw sick absences decline to their “normal” pandemic levels as the Omicron variant waned, though the number of people working part-time due to illness remained somewhat elevated.

The number of employees who lost work due to pandemic-driven business closures also dropped in February, though it remained above December levels. Barring the emergence of another significant variant, it is likely that the number of workers affected by business closures will continue to decline as it did throughout most of 2021.

The percent of workers who teleworked because of the pandemic also jumped up significantly in January and then declined in February, though remaining above December levels. Remote working rates have not dropped that fast due to pandemic-related risk aversion and an increase in telework demands from many employees.

The number of workers with unpaid absences, which can be a proxy for misclassified unemployed people, also declined significantly in February. This also likely represents a drop in workers taking unpaid sick leave or unpaid family care leave due to the pandemic.

Overall, COVID’s effects on the labor market were much more muted in February than in January. Last month’s drop in employment rates seems to be a temporary consequence of the emergence of the Omicron variant, and the employment recovery made up for some lost ground.

A Tightening Labor Market

Critically, a tighter labor market is pulling marginal workers back into the labor force and closing some of the pre-existing employment gaps—though important inequities remain. The unemployment rate for workers without a high school diploma hit its lowest level on record last month as firms continued to offer more attractive offers to previously-excluded workers. Rising wages for low-income workers and more stable employment relationships are making the labor market recovery more inclusive, and rapid hiring in sectors like retail trade and leisure & hospitality will further boost demand for workers with less formal education.

The unemployment rate for teenagers, who are usually among the first to lose work during recessions and last to regain it during recoveries, is also extremely low. In May 2021 the teenage unemployment rate hit its lowest level since 1953, and though it has increased marginally since then it remains lower than at any point between 1956-2020.

The recovery has helped to close some of the racial employment gaps that emerged during the pandemic, but it has by no means eliminated racial inequity in the labor market. The unemployment rate for Asian workers has completely caught up to the unemployment rate for White workers, though a significant gap remains between White workers and Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino workers. Still, the racial unemployment gap has closed significantly for Hispanic/Latino workers since the start of the pandemic and looks to finally begin closing for Black/African American workers. The unemployment rate for Black/African American workers declined from 6.9% to 6.6% in February, putting it lower than at any point before 2018, and the unemployment rate for Hispanic/Latino workers declined from 4.9% to 4.4%, putting it lower than at any point before 2019. A continuation of the hot labor market should further shrink racial unemployment gaps, though it is unlikely to fully close these gaps on its own.

The number of Americans who are working part time due to economic reasons (a good indicator of underemployment) remains below pre-pandemic levels but jumped up significantly in February. This may not be bad news, however—it would be consistent with the idea that firms gave winter seasonal workers fewer hours instead of firing them. Strong labor demand has kept layoffs at record lows as firms work hard to retain workers, and a temporary jump in part time employment might be the result of companies looking to keep marginal workers on payroll.

Conclusions

Overall, the job market recovery remains strong despite the continuing threat posed by COVID-19. High labor demand is continually boosting employment levels, and the waning impact of the pandemic is allowing more workers to return to the labor force.

After two years, we are nearly approaching the pre-pandemic employment rates—but that is by no means the upper limit on America’s labor market. Comparable countries like Japan or Canada have prime age employment rates of nearly 85%, which is a great deal more than the 80.5% that the US achieved before the pandemic. In fact, the US has been a significant laggard in labor market strength among high income countries, with Italy being the only country with materially worse employment rates.

And yet, the pre-pandemic labor market was strong enough that it was beginning to reverse some of America’s longstanding negative economic trends. The racial unemployment gap was closing and Black/African American workers saw their highest employment levels in decades. Wage growth was strong, especially for workers at the bottom end of the income distribution. Labor productivity growth was increasing and household balance sheets were improving. If all of that could be achieved by 80% prime age employment rates, then going even higher should be a boon for the US economy.