The Powell Shock

An Aggressive, Uncertain Fed Comes Swinging Against Inflation

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 7,100 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

“A 75 basis point increase is not something that the committee is actively considering” said Jerome Powell.

Six weeks later, the committee passed a 75 basis point increase—the largest in 30 years—with only one dissent.

The move was well-anticipated by financial markets—doubts were priced in even as Powell put cold water on the idea back in May. A steady march of news—starting with rising gas prices, feeding into a hot CPI report, and ending with an article in the Wall Street Journal that (rightly or not) was seen as Federal Reserve insiders leaking info to set expectations for a 75 basis hike ahead of their June meeting.

Putting the palace intrigue aside, the Federal Reserve was, in effect, trading some of its credibility in guiding the expected path of interest rates for credibility in fighting inflation. Jerome Powell cited a hot May CPI print and a rise in consumer inflation expectations as the drivers of the hawkish move—but outside of further increases in gas prices the level of inflation in the May print should have been anticipated six weeks ago and moves in consumer inflation expectations have not scared the Fed previously.

In truth, it is likely that the steady storm of upside surprises to inflation have created an unacceptable policy environment for the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Headline inflation is simply too high for the Fed to comfortably look past rising energy prices; a strong response was demanded for political reasons just as much as economic ones.

As recently as three months ago the Fed was still waiting for supply. Sure, rates would have to increase—but the central bank’s projections relied on inflation decreasing primarily through the untangling of supply chains, growth in labor supply, and improvements in the pandemic health situation.

No longer—the Fed wants to bring the pain. The FOMC’s updated projections under “appropriate monetary policy” call for three successive years of increasing unemployment rates, two years of rising interest rates, and a slower pace of real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth. Powell wants worsening financial conditions, and the FOMC seems less confident than ever that it can stick the soft landing.

Projecting Pain

We're not looking to have a higher unemployment rate...we don't seek to put people out of work

Four times a year, the FOMC participants release their projections under “appropriate monetary policy” for key economic variables over the near future and in the long run. These get compiled into the Summary of Economic Projections—part forecast, part wishlist from the FOMC. This meeting saw median projections revised heavily across all major categories. Inflation projections were revised up for 2022 and GDP growth estimates were revised down for the next three years.

However, the real pain comes from the interest rate and unemployment projections. The median interest rate projections were revised up nearly a percent and a half for 2022 and nearly a full percent for 2023. Importantly, rate cuts are projected for 2024—essentially baking in a short-term yield curve inversion. The unemployment rate is projected to increase for three successive years—starting at the current level of 3.6% and reaching 4.1% in 2024. Never in modern American history has the unemployment rate increased by so much for so long without a recession—the closest possible analogies would be the 1994 and 1984 hiking cycles when unemployment remained unchanged for several years.

Not trying to induce a recession now. Let's be clear about that. We're trying to achieve 2 percent inflation consistent with a strong labor market. That's what we're trying to do.

The sort of “soft landing” scenario in which rising interest rates tame inflation without significant collateral damage to employment or output seems less likely—and the Federal Reserve seems less keen to err on the side of caution. Jerome Powell left the door open to further significant interest rate hikes in upcoming month and implied that tighter policy will be sustained until monthly inflation rates improve significantly. That means worsening financial conditions and continued real interest rate increases until price growth slows or reverses.

Financial Pain

With us having really just done very little in the way of raising interest rates, financial conditions have tightened quite significantly through the expectations channel, as we've made it clear what our plans are. So, I think that's been a very healthy thing to be happening.

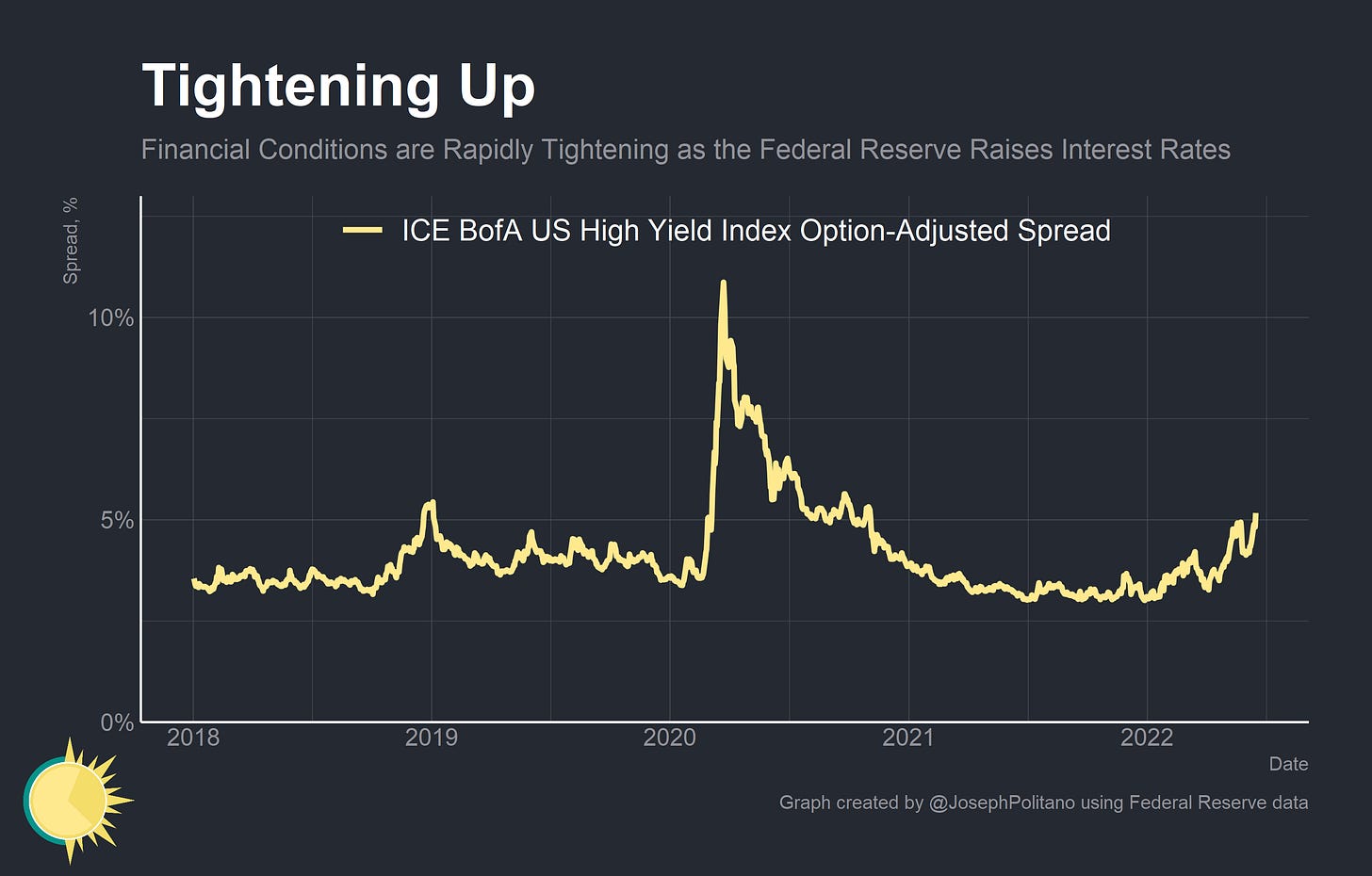

Indeed, in the week since the May CPI report was released financial conditions have only worsened across the board. High yield credit spreads, which measure the difficulty of borrowing and probability of default for the riskiest companies, have increased to levels not seen since late 2020. Spreads are rapidly approaching the highs of late 2018 and early 2019 when the Federal Reserve was forced to back off its previous rate hiking cycle due to a slowing economy and rising recession fears.

The lack of clear communication from the Fed is dramatically increasing interest rate volatility too. The MOVE interest rate volatility index is approaching its COVID-crisis highs as treasury markets remain extremely unstable by historical standards.

Underscoring that instability, real interest rates have also increased dramatically across all maturities in the last week—and the real yield curve is quickly flattening. The inflation-adjusted 5 year interest rate is up nearly 50 basis points since before the CPI data was released, and the inflation-adjusted 10 year interest rate is up more than 30 basis points.

At the same time, bond-market-based measures of inflation expectations derived from Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) have been decreasing significantly. Given the inflation and liquidity risk premiums embedded in breakeven inflation expectations alongside the tendency of the CPI to outpace more comprehensive measures of inflation, 5 year TIPS breakevens are rapidly approaching the range consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target. To achieve that under these circumstances is no small feat—the delay between TIPS issuance and inflation adjustment means that part of May and all of June’s CPI are currently embedded in inflation breakevens. Given the large increases in gas prices over the last two months, the recent dip in inflation expectations is consistent with a massive decrease in expected aggregate spending. Importantly, short run and long run inflation expectations are both close to being anchored at normal levels consistent with the Fed’s inflation target.

We're well-aware that mortgage rates have moved up a lot and you're seeing a changing housing market. We're watching it to see what will happen. How much will it really affect residential investment? Not really sure. How much will it affect housing prices? Not really sure, it's I mean, obviously we're watching that quite carefully.

Mortgage rates have also risen to the highest levels in more than a decade, and at the fastest pace in modern history. That’s already having a direct effect on the housing market—new housing starts were down more than 14% in May and permits were down 7%. It’s also killing refinancing activity, with housing data provider Black Knight estimating that only 472,000 high-quality mortgage candidates remain who could benefit from refinancing at current rates—that’s down nearly 95% from last year. Homeowners have a lot more equity than during the 2008 crisis, and a price drop would be a historical anomaly, but a cooler housing market is practically inevitable if mortgage rates stay this high.

Conclusions

Our objective is to bring inflation down to 2% while the labor market remains strong. What's becoming more clear is many factors we don't control will determine whether that's possible or not.

-Jerome Powell

At this point, it is almost trite to say that the Federal Reserve can’t just print more motor vehicles, barrels of oil, bushels of wheat, or housing units. But they do have tremendous power to control financial conditions, aggregate demand, and employment outcomes. Pushing for worsening financial conditions until years of significant unemployment increases manifest is tantamount to promising to inflict serious blows to the labor market when it still remains below potential. But monetary tightening doesn’t have to incur a recession—the 2015-2016 and 2018-2019 periods contained significant tightening amidst a generally weaker economy and a higher probability of recession than corporate bond markets are currently pricing in, and yet no recession materialized. This was partially due to the fact that policymakers were slower, more deliberate, and more nimble than in previous cycles.

The Volcker shock was about reestablishing the credibility of the Federal Reserve and monetary policy in containing inflation—famously by spilling “blood, lots of blood, other people’s blood” in a series of punitive rate hikes. But that pain was required after a decade of rising underlying inflation and rising inflation expectations. If expectations had unanchored briefly this year, the “Powell Shock” and the blood spilled since has brought them back down—inflation breakevens hit 3.6% in March and have shrunk back to normal levels since then.

Inflation credibility is incredibly important, but the way the Fed is going about establishing that credibility is coming at a large institutional cost. The consistent problem of US monetary policy since the implementation of the new policy framework is that the Fed will not communicating a clear enough reaction function or policy path, introducing more financial instability into the system for little benefit. Clearer communication is necessary to rebuild trust and lower volatility across the board—which will also be necessary for effective inflation-fighting.

Ultimately, it lies within the Federal Reserve’s hands if we’re able to manage a “soft landing” that gets inflation down without crushing employment.

Joseph, I really appreciate your thoughts on this, but I wonder about the Fed's credibility issues. As I recall, when Volcker led the Fed on its spree back in the early 80's, there was no commentary, no forward guidance, no communication at all. The Fed simply adjusted the money supply to achieve the results they were seeking and were quite successful doing so. The lack of communication, I believe was critical because market participants had varying opinions as to what may happen and were positioned according to their own views, not the Fed's commands. Hence, positions were generally smaller and less leveraged so shocks were less disruptive. Ever since forward guidance became a policy tool, everybody has known which way to be, which was generally long assets, and were willing to lever up those assets b based on ZIRP and the conviction that the Fed had their back. It seems to me the current problems for Powell are entirely of the Fed's own making as they have hamstrung themselves from moving as they would like to in order to prevent an absolute collapse. And given what we are seeing in the housing market to start, it appears they have only a limited chance to be even partially successful.

More than a decade of too easy money cannot be corrected in one or two years, at least not without breaking a lot of things, at least in my view.