The Tariff Exemption Behind the AI Boom

Data Centers get Tariff-Free Imports. Why Shouldn't we All?

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing, you’ll join over 72,000 people who read Apricitas!

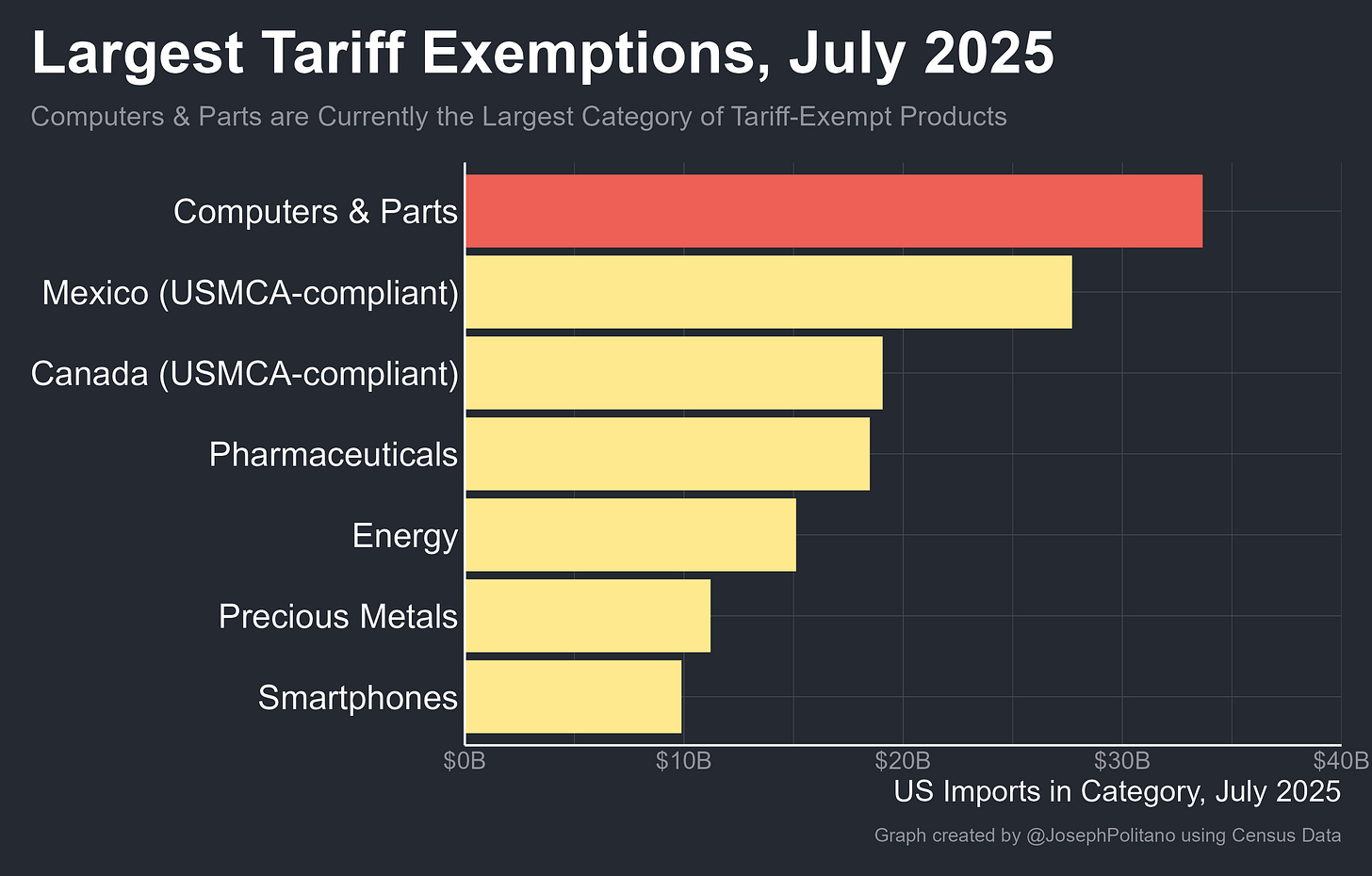

During his second term, Donald Trump has pursued the largest trade war in modern American history, sending tariffs to the highest level since the infamous Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930. Yet at the same time, roughly half of American imports remain completely exempt from his trade war—billions in goods are carved out because of their country of origin or product category. Mexican and Canadian goods that comply with Trump’s first-term USMCA deal remain tariff-free, as do energy products like crude oil, precious metals like gold, and products slated for future tariffs like pharmaceuticals. The single largest of these exemptions, covering an astonishing $34B of imports per month, is for computers and parts—an exemption that AI companies are now completely reliant on for their record-breaking investment push.

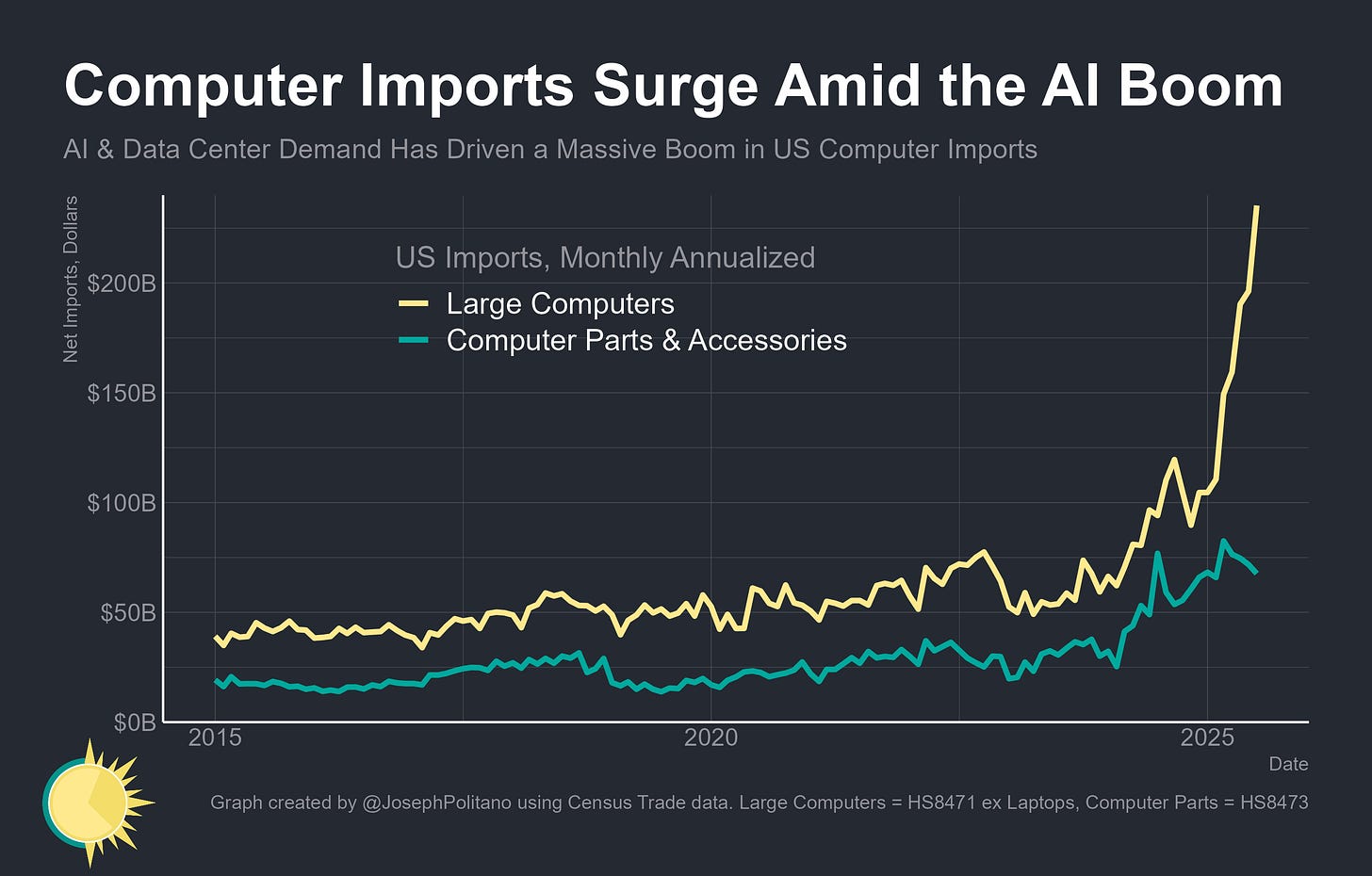

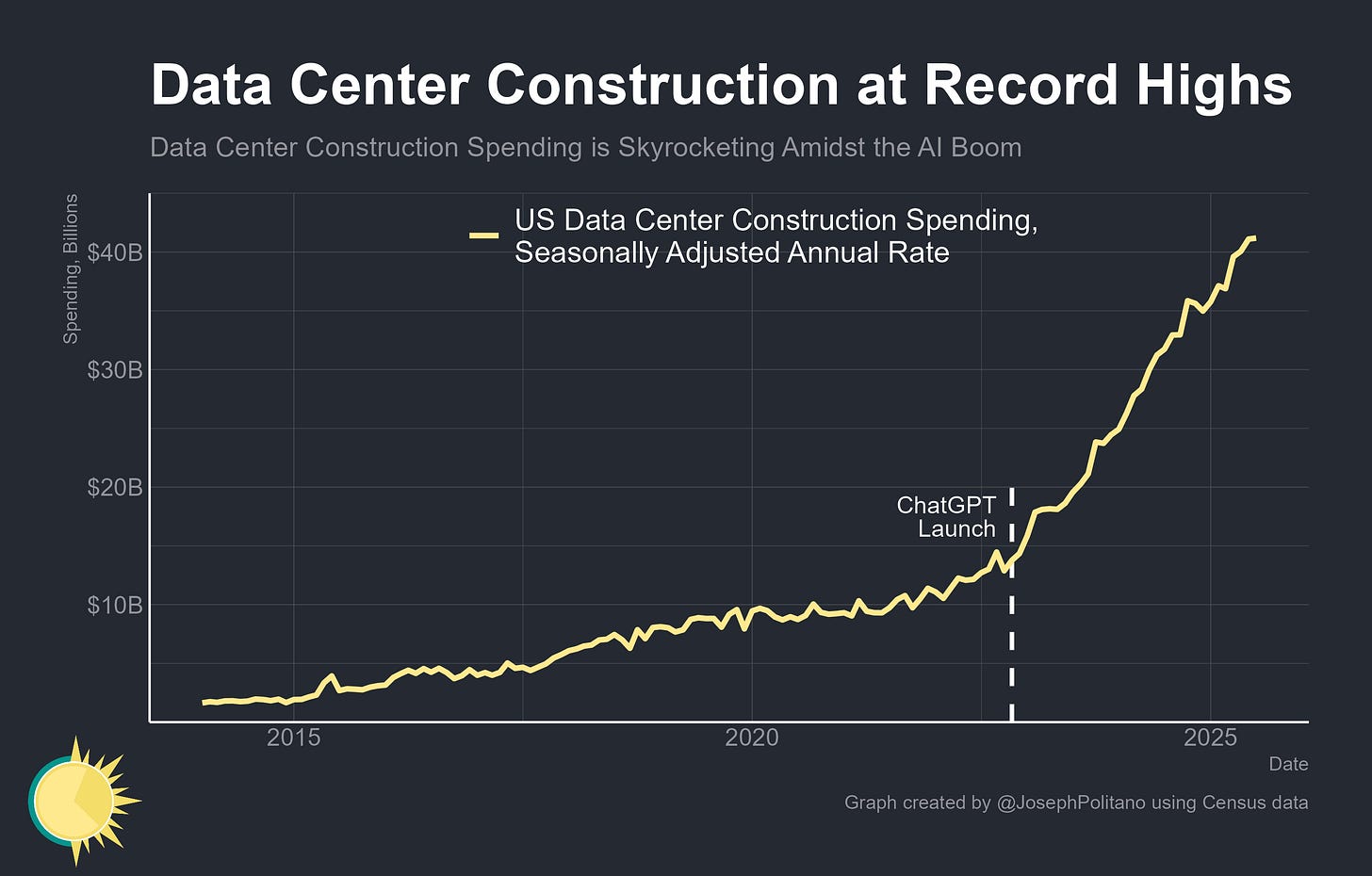

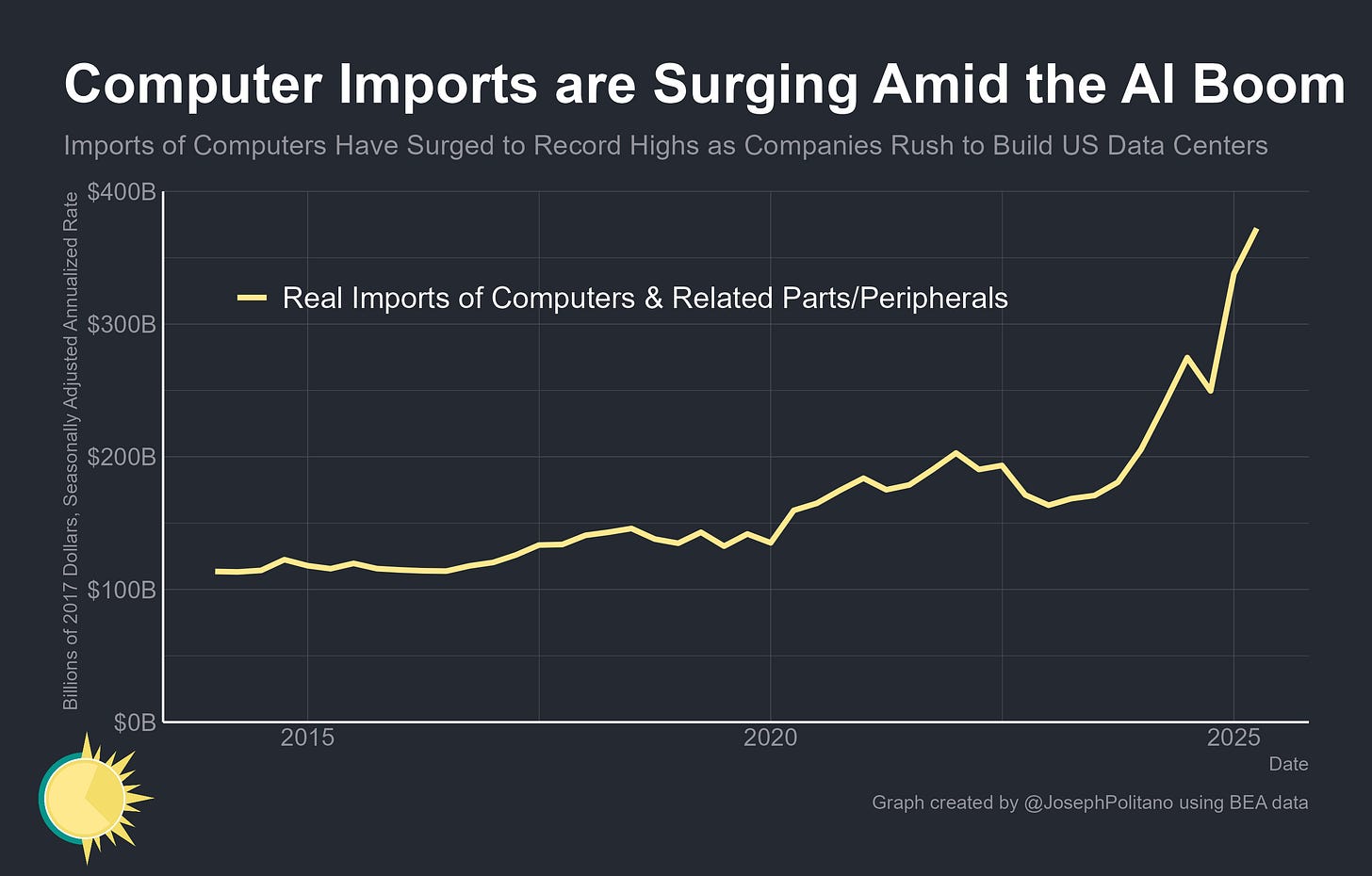

American tech companies have been in a frenzy to develop increasingly advanced AI models ever since the release of ChatGPT in late 2022. Training and running these models require processing unprecedented levels of information, which in turn requires some of the largest data centers ever built, which themselves require thousands of advanced computers to operate. However, the modern electronics used in data centers have the most complex supply chains in human history, and America makes up only a small part of the direct manufacturing involved. Thus, imports of the large computers commonly found in data centers now exceed $235B annualized, up 227% compared to before the launch of ChatGPT, while imports of computer parts exceed $67B annualized, up more than 100%. Without this exemption, importers would have paid an extra roughly $8.9B so far this year (naively applying the 10% baseline tariff rate that has been in place since April), or roughly $19.2B (applying the country-level tariff rates in place as of today). The current AI boom would simply be impossible if tech companies had to pay the same tariffs that car manufacturers or homebuilders currently face.

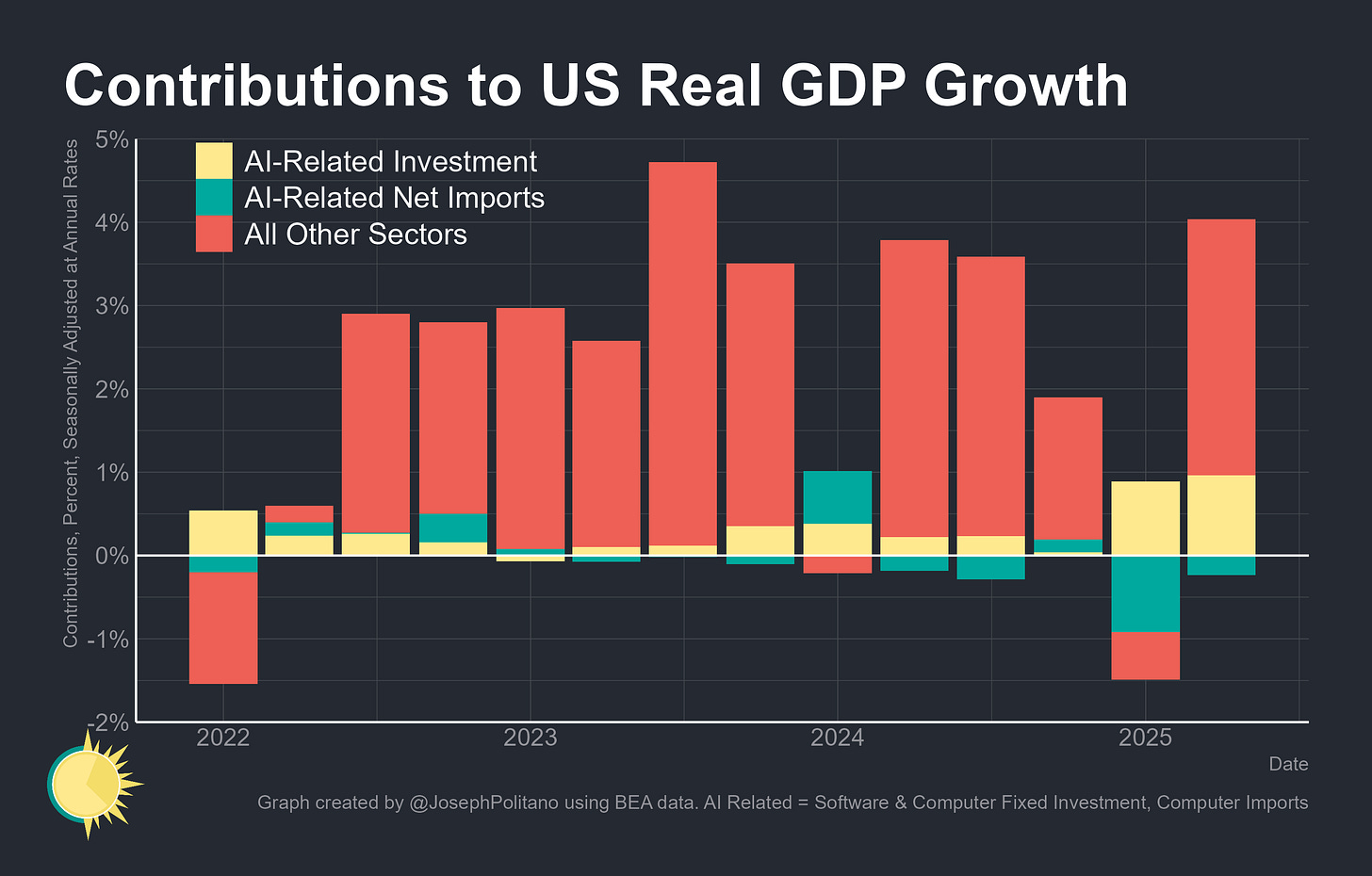

Meanwhile, US economic growth is increasingly driven by today’s AI buildout. In Q2, computer & software investment officially contributed roughly 0.71% to the 3.8% annualized pace of growth, which is almost certainly an underestimate given how official data struggles to capture investment in electronic parts. Large parts of the US economy are now totally dependent on this tariff exception for computer imports.

On one hand, this is a victory for free-traders: even the world’s most pro-tariff administration cannot fully escape economic reality and remains unwilling to mess with its most important supply chains. This massive tariff carveout is much of the reason why, despite the trade war, America’s stock market keeps surging to new highs, and its economic growth has beaten the dire forecasts from early April. It serves as a tacit admission that a full-scale trade war would kill America’s golden geese.

On the other hand, the pick-and-choose style of tariff exemptions means the Trump administration is punishing the rest of the economy to the benefit of tech companies. Tariffs are making it more expensive to build or buy anything unrelated to computing, so consumers and businesses are effectively being incentivized into the AI ecosystem. The White House is making a giant gamble on artificial intelligence as the future of the world’s economy, and if they’re wrong America will have wasted tens of billions of dollars that could have gone to more valuable investments.

More broadly, the AI boom raises a fundamental challenge to Trump’s entire trade strategy. If free trade is delivering such amazing results for the one sector still able to enjoy it, why are we subjecting farmers, manufacturers, and families to intense protectionism? In other words, if data centers get to be exempt from tariffs, shouldn’t we all?

Breaking Down the AI Investment Boom

The planet’s six largest companies—NVIDIA, Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, and Meta—are all American tech giants deeply enmeshed in the AI ecosystem. Together, they have a valuation exceeding $15T and are investing hundreds of billions in the physical infrastructure underpinning AI development. In the United States, construction of data centers now exceeds a $41B/year pace, rising more than 200% over the last three years. Today, America is spending nearly as much on data center construction as it spends on office buildings.

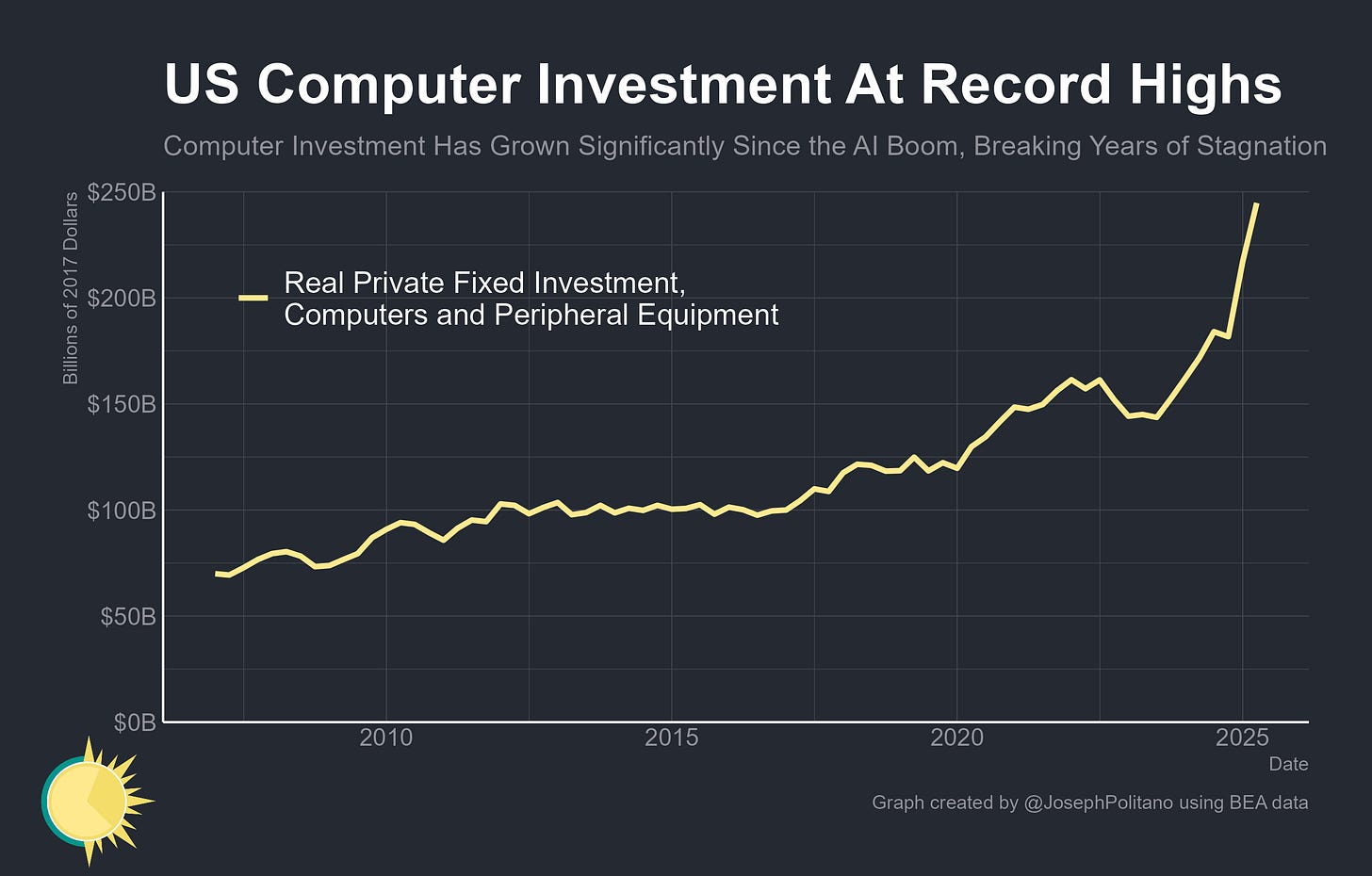

Yet those eye-popping numbers only reflect the facilities themselves, excluding the computers and other electronics housed inside. The brains of AI data centers are much more valuable than their skeletons, and thus US investment in computers & electronics far outstrips the amount spent on data centers alone. Fixed investment in computers & related equipment has risen to nearly $250B after adjusting for inflation, a record high and a nearly-$100B increase over the last year.

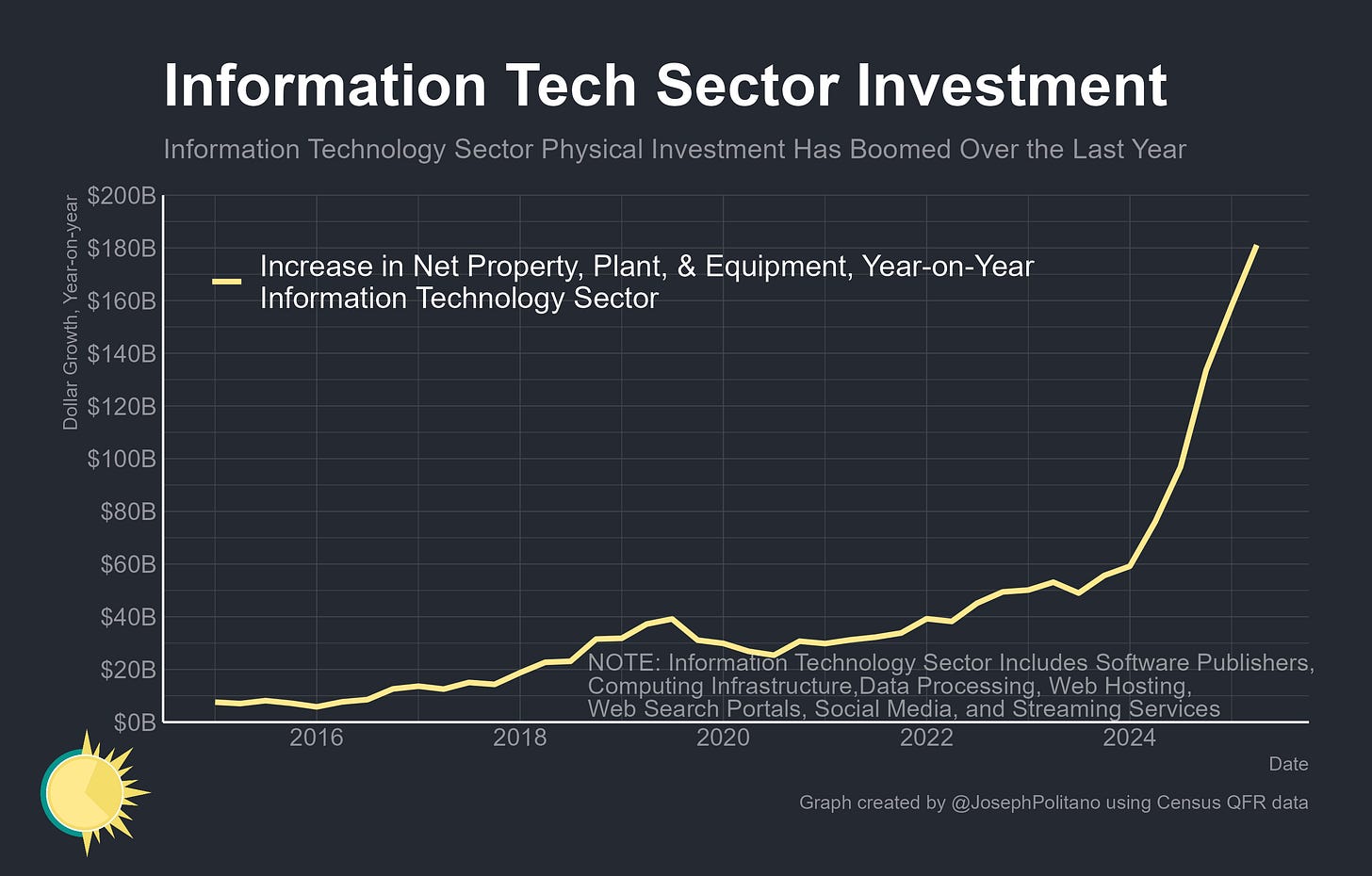

It’s hard to know precisely how much of that investment is directly attributable to AI—after all, computers & data centers are used for a wide variety of digital tasks, including video streaming, cloud storage, data management, etc—but we can get a better idea by looking at the spending of tech companies specifically. Businesses in the information technology sector have increased their holdings of property, plants, & equipment by more than $180B over the last year, a record high that is more than triple the 2023 pace.

Breaking Down the AI Import Boom

That rising data center investment requires record amounts of foreign inputs since advanced computer manufacturing is a highly complex and extremely globalized industry. The AI investment boom is dependent on imports of GPUs, computers, parts, and other electronic equipment from countries like Taiwan, Mexico, and Vietnam. Those imports are now skyrocketing, reaching more than $370B annualized after adjusting for inflation, and show little signs of slowing down.

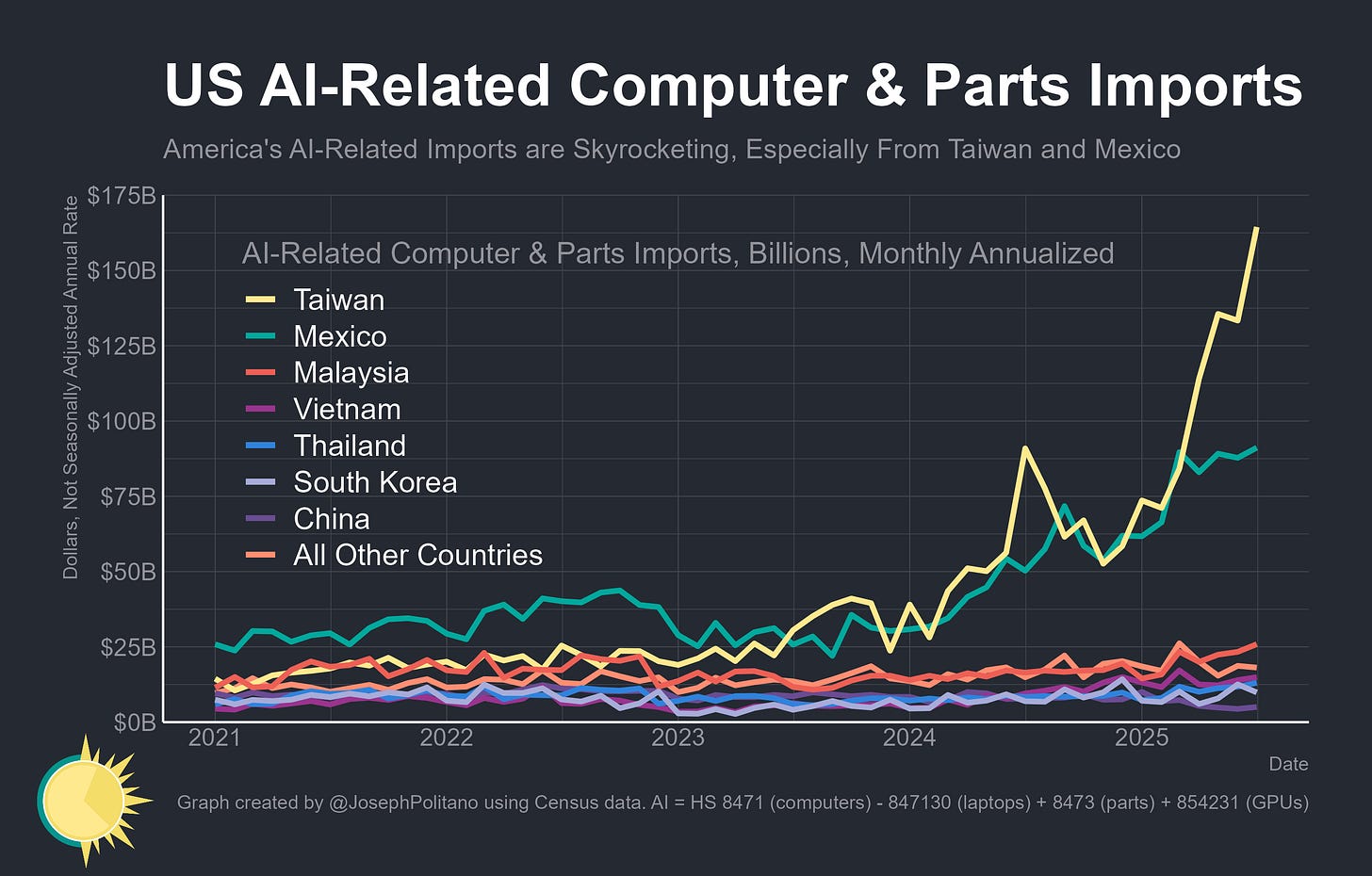

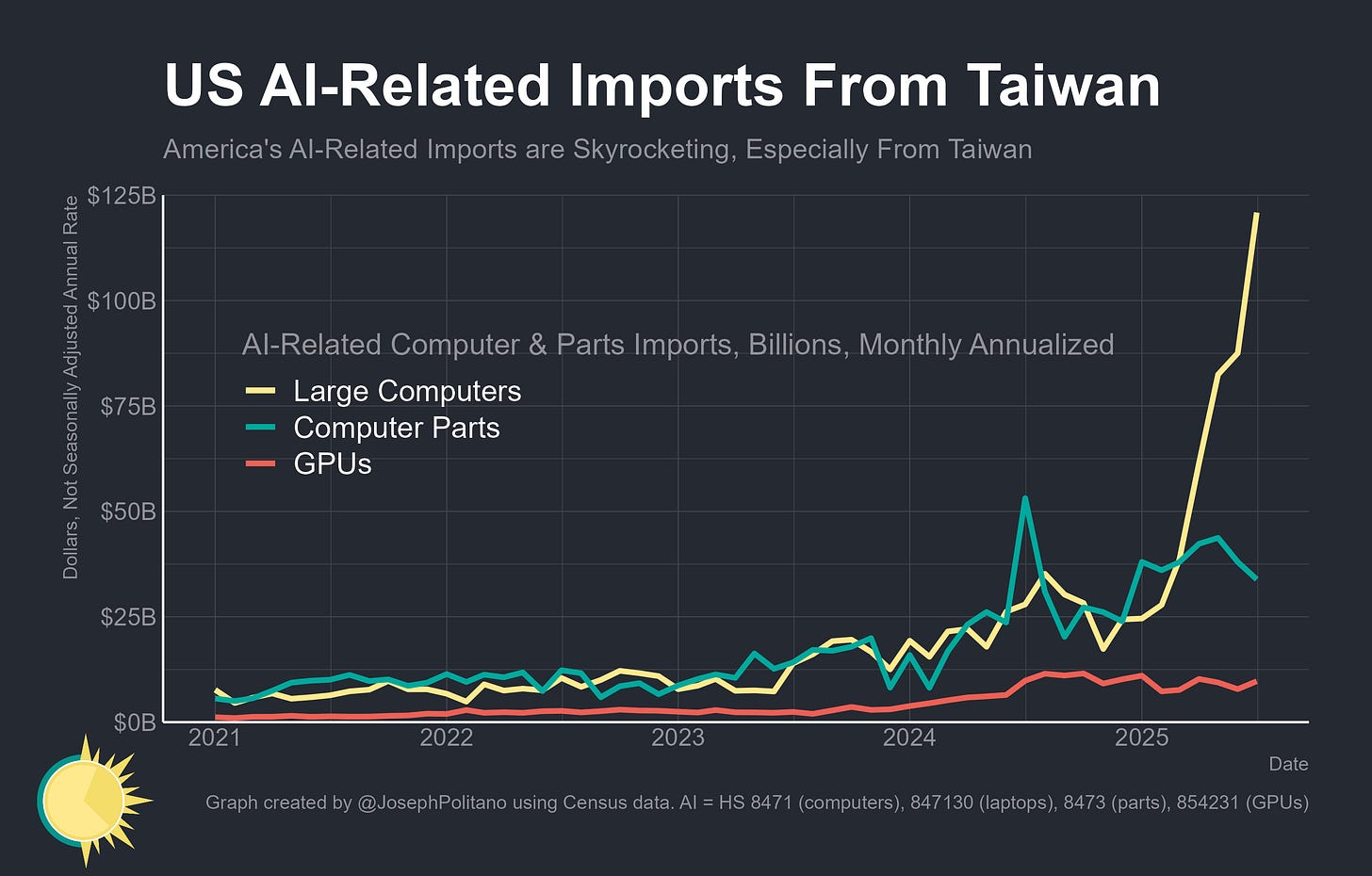

The majority of America’s AI-related imports come from Taiwan, the headquarters of world-leading semiconductor manufacturing firm TSMC. US imports from the island nation have skyrocketed from a roughly $25B/yr pace in late 2023 to a $160B/year pace today. Imports from Mexico have also increased significantly, more than tripling over the last two years, while imports from smaller electronics manufacturing hubs like Vietnam and Thailand have risen at a more modest pace. Only computer imports from China have declined this year, as the 20% tariff on all Chinese goods leaves no exemptions for electronics like the tariffs on Vietnam, Mexico, or Taiwan.

Breaking down the trade with Taiwan, the vast majority of imports come in the form of larger computer systems designed to slot into the server racks of American data centers. Those imports have nearly quintupled since the beginning of the year as companies rush to bring as many computers as possible into the country. Data centers also rely on a complex array of parts for their regular operation, and imports of the specialized parts made by companies like TSMC have risen to roughly $30B annualized. Imports of GPUs themselves have also increased significantly, although they make up only a small share of direct US-Taiwan trade—most GPUs are already assembled into computers before boarding ships for America.

The Notes You Don’t Play

Heavy tariffs are a form of industrial policy, allowing the government to intervene directly in the economy to support certain sectors at the expense of others. That primarily happens through supply channels—American aluminum manufacturers currently enjoy massive government support via the 50% tariffs on aluminum while the downstream airplane manufacturers reliant on aluminum suffer higher input costs. Yet tariffs and their exemptions can also shape investment decisions by changing the relative price of capital goods—right now, it is much more expensive to build an aerospace manufacturing plant relative to a data center because only the plant’s equipment will be hit with tariffs. Real US investment in structures has sunk since the beginning of this year while investment in industrial equipment grew tepidly; only tariff-exempt electronics investment is booming.

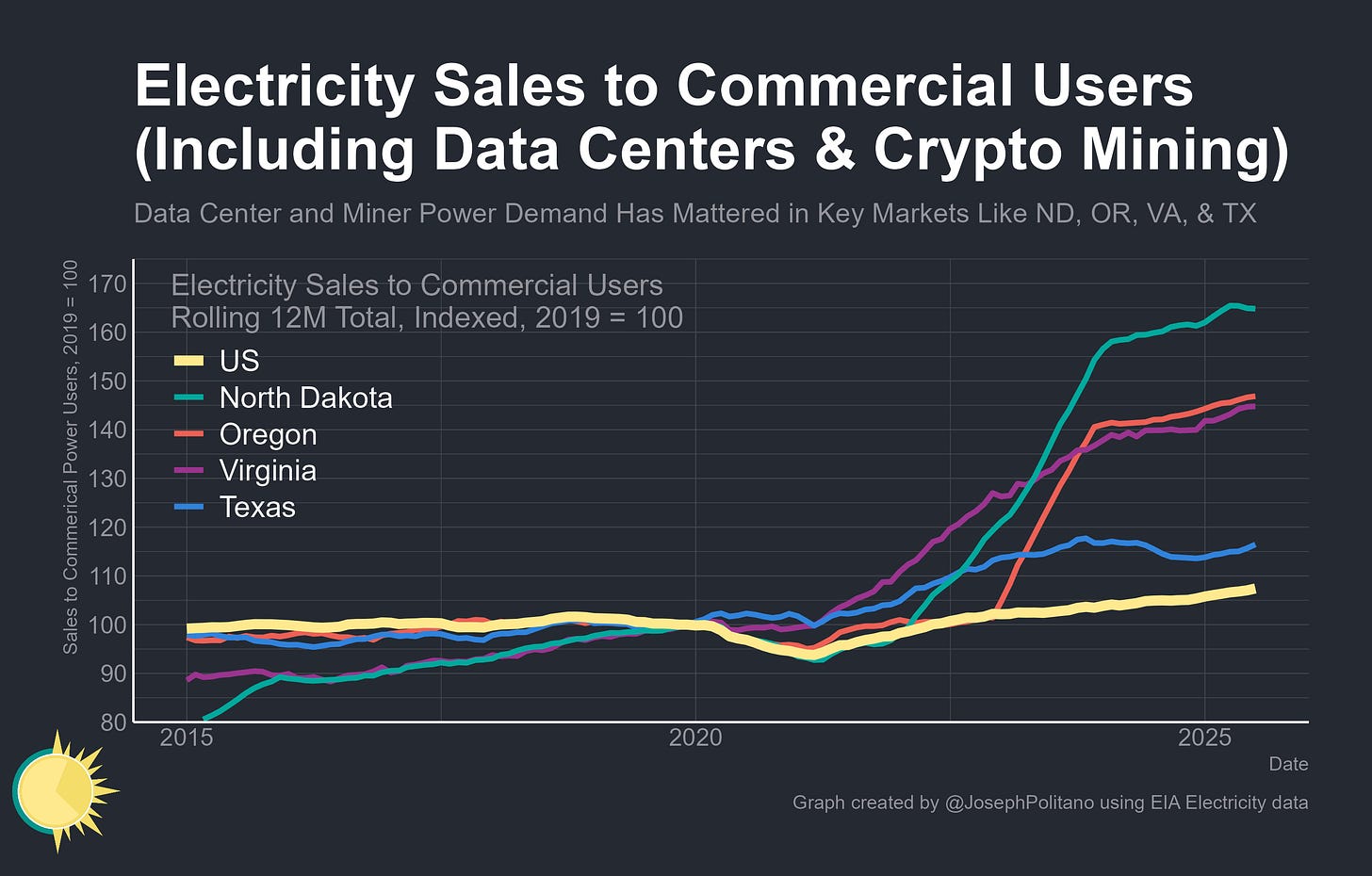

The other key issue is that data centers are not just dependent on electronics themselves, they are also dependent on electrical infrastructure for the industrial-scale power required to run modern AI models. Electricity sales to commercial users (which includes data centers) have risen by roughly 7% since 2020, making it the largest contributor to overall US load growth ahead of residential and industrial sales. Yet in specific submarkets, the impact of data centers has been much, much larger—annual commercial electricity consumption in Virginia has risen by roughly 45% (24 TWh) since 2019 as the megacluster “Data Center Alley” continues to grow in the DC exurbs. Oregon has seen a similar 47% (8 TWh) spike in commercial power consumption, Texas has also seen a more than 16% (21 TWh) increase, and tiny North Dakota has seen a 65% increase (4.6 TWh) after the construction of a handful of data centers.

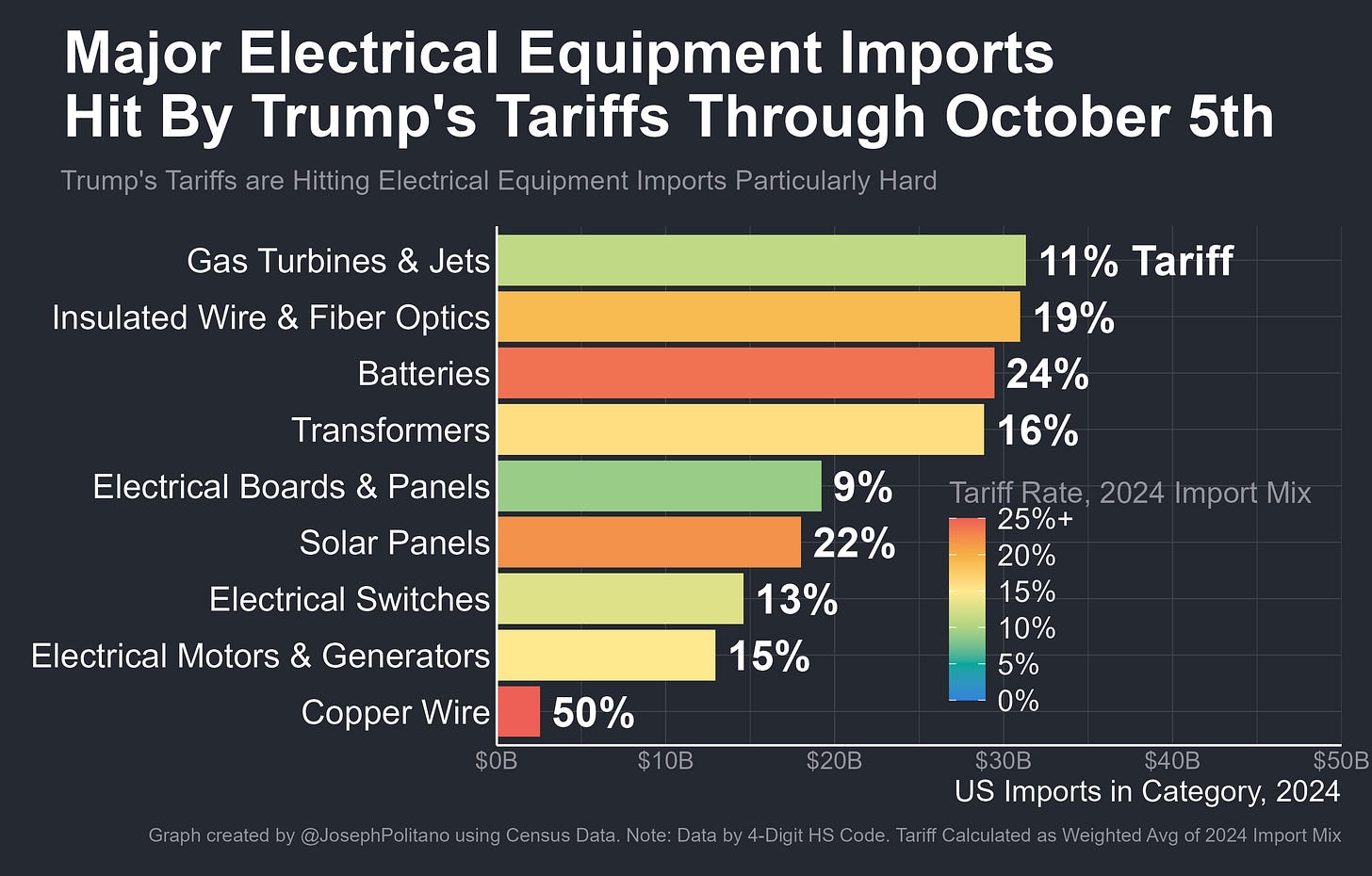

However, Trump has not exempted electricity generation infrastructure from tariffs like he has with data center computers. Transformers, batteries, switches, and more all face substantial tariffs, making it harder for power companies to meet the electricity demands of the AI boom. In fact, Trump is specifically targeting certain electrical equipment for extra-high tariffs—copper wiring faces a 50% tariff, generators face elevated tariffs based on their steel content, and the Department of Commerce has started an investigation into wind turbine imports that sets the stage for future tariffs. At the same time, the administration has been trying to forcibly cancel many clean energy projects by revoking their funding or permits, exemplified by the recent stalling of the nearly-complete Revolution Wind project in Rhode Island.

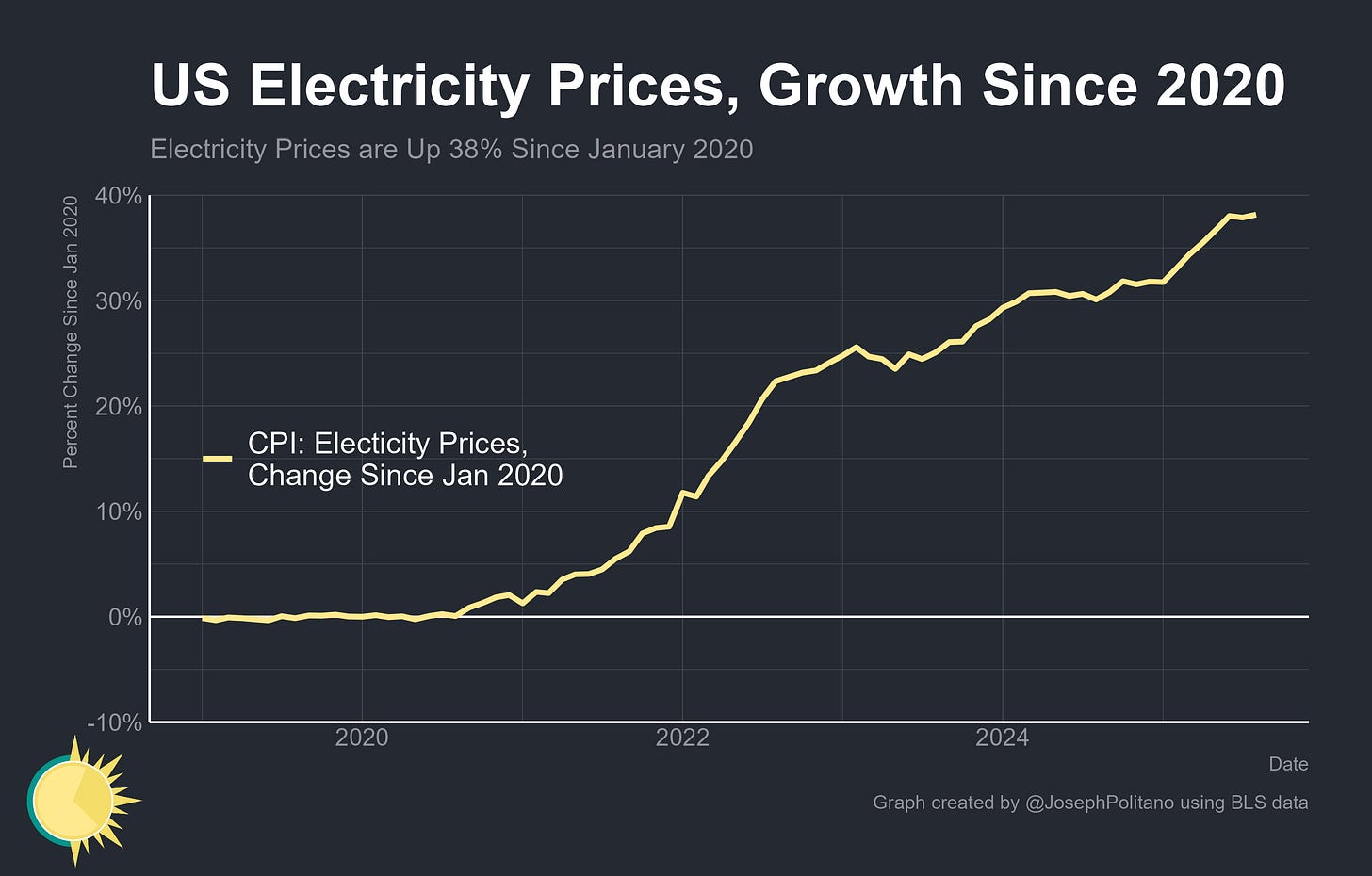

The obvious result of a policy package that taxes electricity investment but exempts data center investment just exacerbates the problems caused by a power grid already struggling to keep up with rising demand. US construction of powerplants and electrical infrastructure has stagnated in recent years, sliding down from their late-2023 highs and holding near $150B/year even as the AI boom accelerates. Since the start of the year, the US Energy Information Administration has cut its 2025 renewable capacity growth forecast even as it has raised its coal & natural gas capacity growth forecasts. All of this is part of the reason US electricity prices are up more than 6% when compared to last year and are projected to rise even further.

How the Electronics Exemption Could End

This tariff exemption for computer imports has always been billed as temporary, even though the Trump administration has thus far proven unwilling to close it. Back in April, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said that electronics tariffs would be coming “in a month or two”, and then in early August, President Trump said they would be signed in the next two weeks, only for both deadlines to pass uneventfully. This would not be the first time a “temporary” exemption was just made functionally permanent (the 30-day pause for most tariffs on Canada/Mexico is now more than six months old) but it’s still worth examining what possible upcoming semiconductor tariffs could look like.

The current rumors of chip tariffs come in two broad shapes. Most likely, Trump will make an announcement similar to the one he recently made for pharmaceuticals—insanely high tariffs, but with a massive exemption for any company that “invests in the US.” Reportedly, some versions of this plan require a 1:1 ratio of imports to promised future semiconductor production, forcing the US into eventual aggregate “self-sufficiency” without strictly taxing every chip that crosses the border. In practice, most multinational electronics manufacturers (like TSMC) already have some large-scale investments within the US that they can point to, and so the administration will functionally exempt everything important and only impose tariffs on a small number of Chinese electronics manufacturers.

The administration could also attempt to place tariffs on electronics based on the value of the semiconductors within. This would be the most administratively complex by far, requiring manufacturers to give a price estimate for every single chip and pressing customs agents into enforcing accurate appraisals. This approach would be prohibitively annoying for manufacturers of cars, medical instruments, or other complex machinery, all of which can contain hundreds of different semiconductors that would need to be individually tariffed. The advantage this approach has over standard tariffs is that it would theoretically avoid punishing companies for imports of the many non-semiconductor parts in their finished electronics. Its advantage over the “exemption for investment” proposal is that it would actually set up a concrete incentive for domestic chip production, instead of just settling for promises.

Conclusions

If tariffs truly were such an unalloyed good, the White House would be chomping at the bit to close the largest remaining exemption. By their own logic, electronics tariffs would bring in tens of billions of dollars in revenue and revitalize domestic advanced semiconductor production! Instead, the administration is scared to rock the boat lest a poorly designed tariff hurt tech companies’ stock valuation and halt the domestic data center buildout.

Paradoxically, the White House is unwilling to use tariffs on the technologically valuable industries because those tariffs come with much larger short-term pain. Domestic electronics production is obviously more important to US national security than furniture production, but America is currently imposing 50% tariffs on kitchen cabinets and 0% tariffs on data center computers because the electronics tariffs would kill the AI boom and furniture tariffs will only raise prices for consumers.

In other words, the Trump administration is increasingly gambling the future of the American economy on AI. If they’re right, the US will capture the dual rewards of both coding the tools of the next economic revolution and owning the infrastructure that runs it. If they’re wrong, the US will be left with a bunch of distressed assets and will have dramatically underinvested in the projects that actually mattered. The large tariff exemption for computers is distorting the American economy in ways that could reshape the long-run future of the country.

Yet in the short run, it’s undeniable that the carveout has achieved its desired effect of accelerating America’s AI boom. The US is at the technological forefront of a rapidly expanding industry because of the free trade policies that this administration ostensibly despises. It’s just tragic that this privilege is not extended to businesses outside Silicon Valley.

One of the biggest concerns about tariffs is the opportunities for rent seeking. The Trump administration is carving out exemptions, some quietly, some not so quietly, for favored groups.

This is a direct result of lobbying and may explain party why the stock market isn't moved much by tariff announcements anymore: the tariffs primarily impact the little guys who aren't listed.

If nothing else, this whole fiasco will be studies for years, a kind of natural experiment that will provide us new insights on trade and growth.

Thank you for writing your in-depth pieces! I appreciate how well you explain everything and connect dots for readers. Hope to see more, keep up the great work.

I think the Supreme Court will give back tariff - commerce and taxation authority - to the legislature. I’m curious how quickly the market and supply chains and deals adjust.