Understanding the Fed's Hawkish Pivot

Why the Fed Changed Their Mind on Inflation

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

In December the Federal Reserve struck all references to “transitory inflation” from their policy statement—a phrase that had earned much controversy and mockery. “With elevated inflation pressures and a rapidly strengthening labor market, the economy no longer needs increasing amounts of policy support” said Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell.

Just months prior, the Federal Reserve was seemingly stoic about keeping interest rates low for the foreseeable future. At the September Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, “various participants stressed that economic conditions were likely to justify keeping the rate at or near its lower bound over the next couple of years” while a number of members considered “beginning to increase the target range by the end of next year.” Today, it seems certain that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates by 0.25% at their March meeting—and St. Louis Fed President James Bullard has been calling for a large, sudden .50% hike next month.

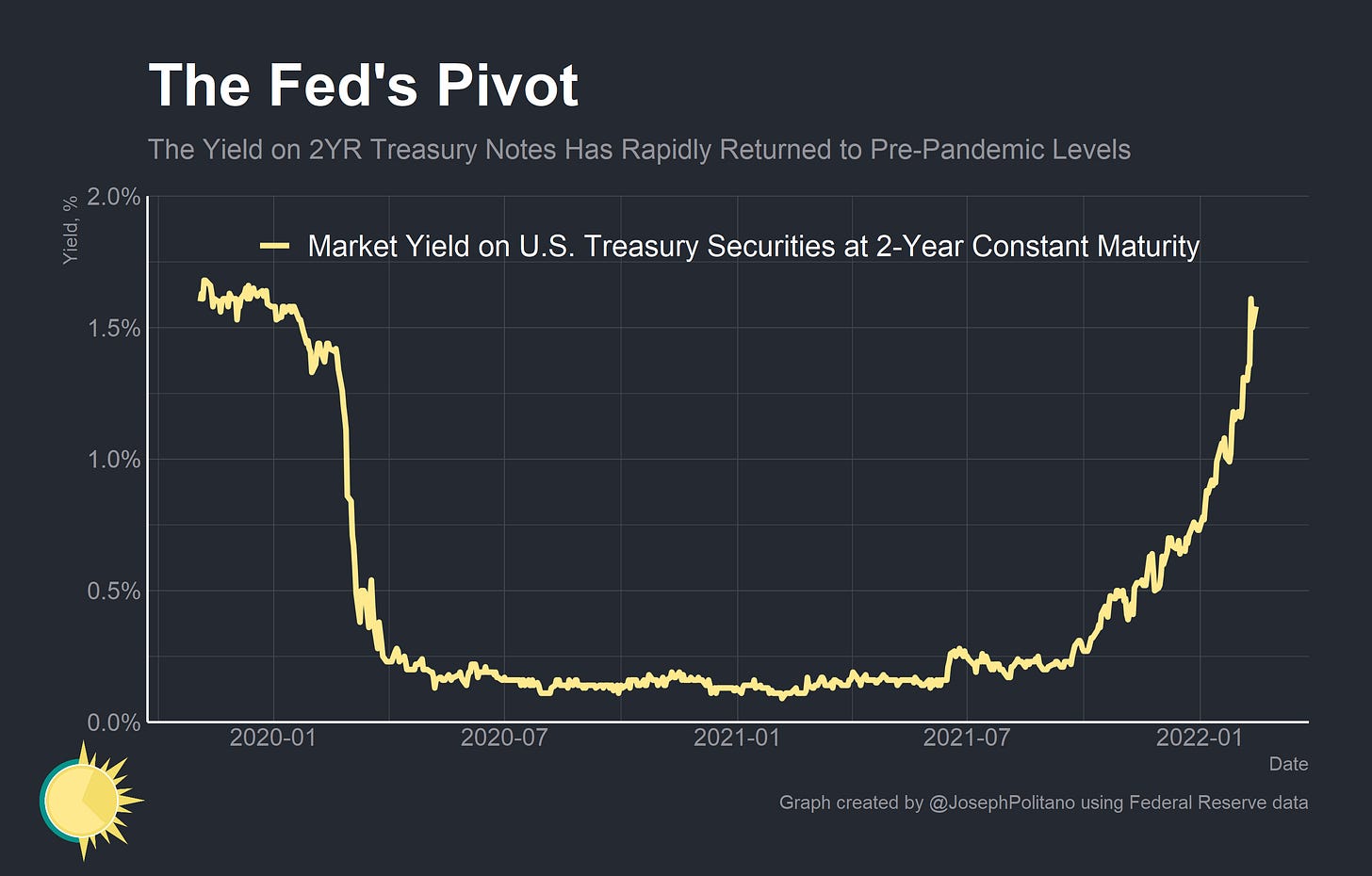

As a result, expected future interest rates and yields on short term government debt have risen at unprecedented rates. Federal Funds futures are currently priced as though short term rates will exceed 1.5% by the end of this year, and yields on 2-Year Treasury Notes have rapidly returned to pre-pandemic levels. What caused the Fed’s about-face on the future path of interest rates?

The short answer is the obvious answer: inflation. The rapid rise in prices has put the Fed increasingly on the defensive about their policy choices. But it is not simply that inflation is high—inflation was high throughout most of 2021 without engendering a monetary policy response. The difference is that, rightly or wrongly, policymakers at the Federal Reserve have stopped believing that goods-driven inflation will abate quickly and have become worried that services-driven inflation will rise significantly. Here’s the view from the Eccles building and why the Fed’s outlook is changing so quickly.

Inflation Fighting

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) grew by 7.5% over the last year—its highest level in more than 40 years. The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI)—which the Federal Reserve targets—grew by nearly 5.8%, also its highest level since the 1980s. That’s well in excess of the 2% target, even when accounting for the below-2% inflation throughout most of 2020. The Federal Reserve had previously been adamant, however, that most of this inflation was due to spikes in goods demand and supply chain issues that would dissipate as the pandemic abated. This belief was backed by data showing that aggregate spending was relatively low, but spending on goods was highly elevated and that a large chunk of inflation was driven by the increasing prices of motor vehicles (which added 2% to CPI) and energy (which added 1%).

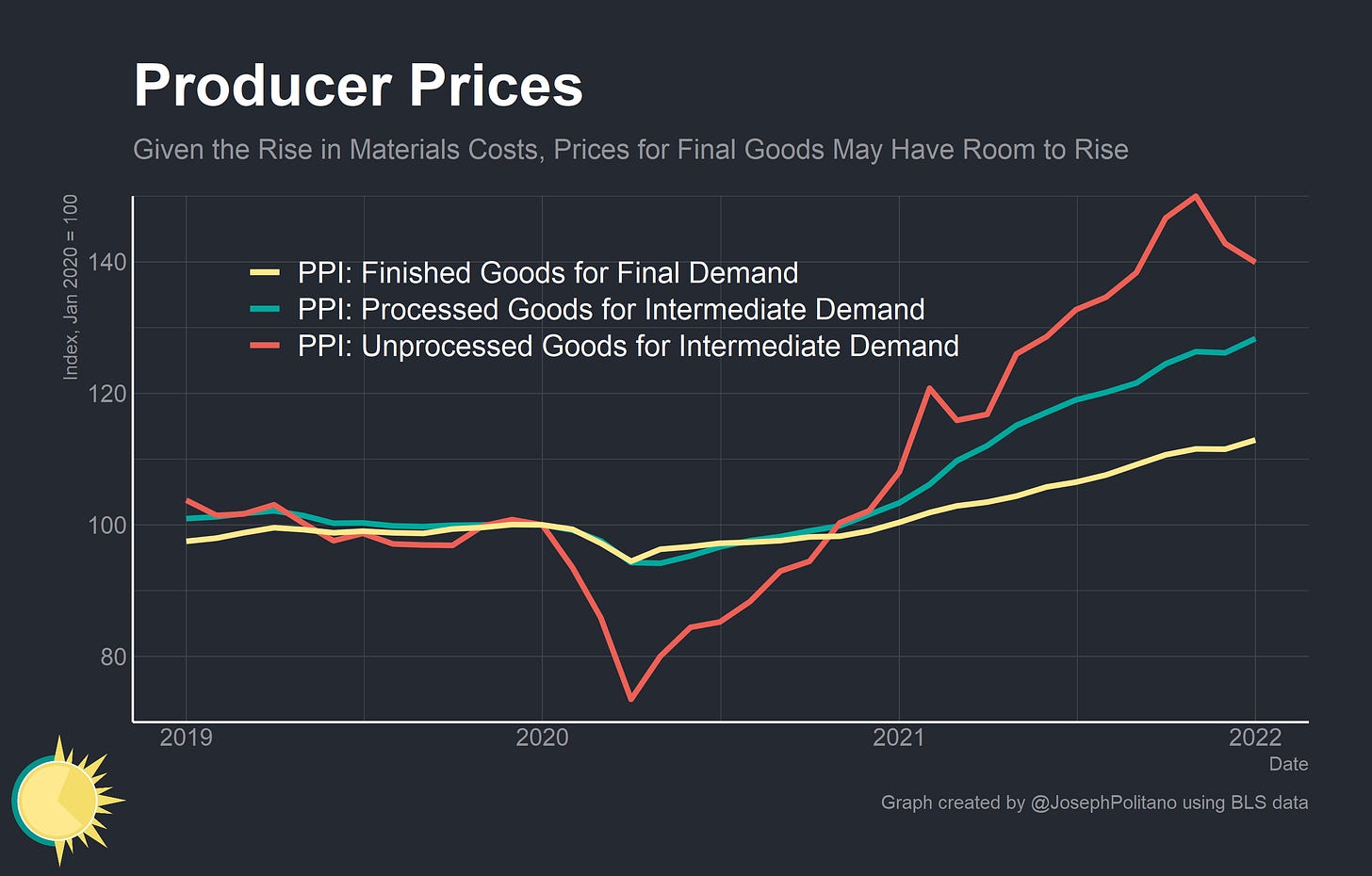

The first part of the Federal Reserve’s newfound inflation worries comes from the goods sector; while supply chains are improving goods demand has remained extremely strong. Critically, manufacturers of finished goods have absorbed some of the hit from rising input costs—but highly sustained goods demand may force them to raise prices further. Imports—which America relies on for a large chunk of its goods supplies—have seen their prices increase given rising ocean shipping costs that show little sign of abating. It is still likely that decreases in goods prices will pull inflation downwards in the coming years, but the size of goods deflation is more questionable.

More critically, the Federal Reserve is likely extremely concerned by the pace of price growth in the service sector. Keep in mind that services make up the bulk of production and consumption in the US, and therefore the bulk of the prices within inflation indexes. Services make up 57% of the CPI, with shelter alone representing 33% of the index. Services prices are also stickier, slower-moving, and much more affected by monetary policy decisions than goods prices—and they have been rising significantly throughout the latter half of 2021. In recent CPI releases, the month-to-month increase in services prices have driven the bulk of inflation—and they are rising faster than they were pre-pandemic. Prices for rent of primary residences went up 0.5% in January alone (the highest monthly growth rate since 1999) and price for services less shelter increased .9% (the highest monthly growth rate since 2005). Critically, rent prices in particular tend to lag economic developments thanks to the structure of rental contracts and CPI methodology. For example, monthly rent price growth did not meaningfully slow down in the wake of the 2008 recession until early 2009 and did not hit zero until the summer of 2009. Private sector data shows much faster rent growth than the CPI data—and while I have written that private sector data is likely significantly overestimating real rental price growth, it is clear that CPI’s data will likely catch up to a degree in the near future. The upcoming dynamics of service sector price growth is likely behind much of the Federal Reserve’s hawkish pivot.

Wages and Spending

Publicly the Federal Reserve is coy about it, but they are also likely worried by the pace of wage growth in the economy. Tellingly, it was high readings from the Employment Cost Index (ECI), not CPI, that initially caused Powell to consider accelerating the tapering of the Federal Reserve’s Quantitative Easing bond-buying program back in December—although the Federal Reserve has said multiple times that they do not believe wage growth is currently contributing to inflation

The New York Times’ Jeanna Smialek asked Powell about the seemingly contradictory statements, and here is part of his response:

if you had something where wages were persistently—[increases in] real wages were persistently above productivity growth, that puts upward pressure on, on firms, and they raise prices. It would take something that was persistent and material for that to happen. And we don’t see that yet. But with the kind of hot labor market readings—wages we’re seeing, it’s something that we’re—that we’re watching.

In other words, the Federal Reserve is watching high wage growth as a signal for future inflation and is becoming increasingly concerned that wages could be growing too fast. They are also partially seeing this as a signal that they have reached maximum employment possible without improvement in the public health situation, and they have been disappointed by the relatively weak growth in labor force participation rates. They are also likely worried that rising wages will support elevated nominal household spending while pushing up labor costs for service-providing firms.

So why is Jerome Powell so shy about saying so out loud? Well, look what happened to Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey: after saying that workers should not demand large pay raises in order to slow down inflation he enjoyed resounding condemnation from British media, unions, and 10 Downing Street. Positive political relations with the public and members of both parties is critical for the Federal Reserve’s function, and publicly coming out against wage growth would be a great way to torpedo public opinion.

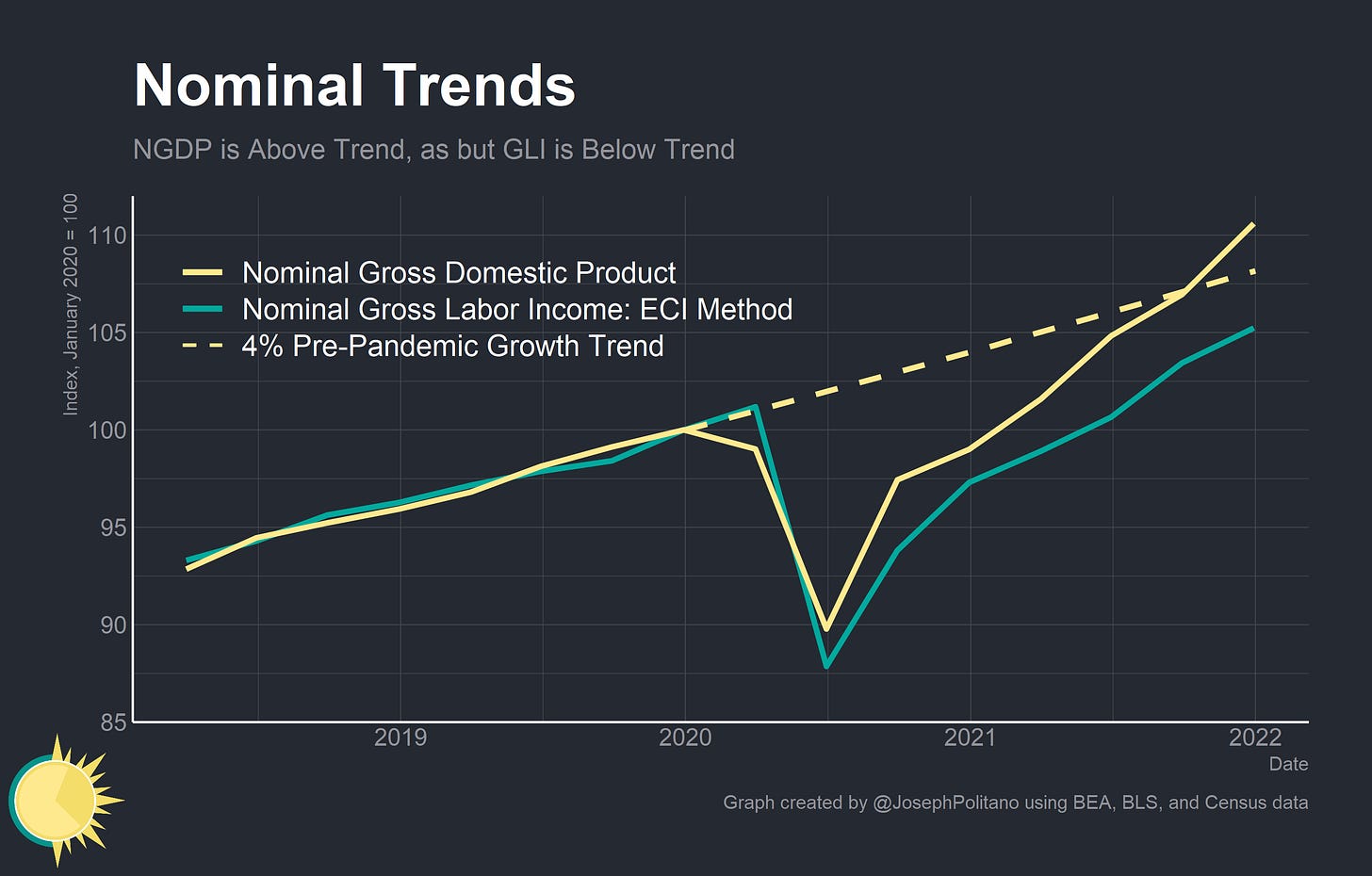

More broadly, the Federal Reserve is likely significantly concerned by the pace of nominal income and spending growth. Nominal Gross Domestic Product (NGDP) has jumped across its pre-pandemic trend recently, and Gross Labor Income (GLI, the sum of wages received by all workers) is closing in on its pre-pandemic trend. While the Federal Reserve has little control over supply chains or pandemic response, they can control nominal income and spending patterns. A large part of the reason for recent policy tightening, therefore, is to restrain NGDP and GLI growth in order to tamp down inflation.

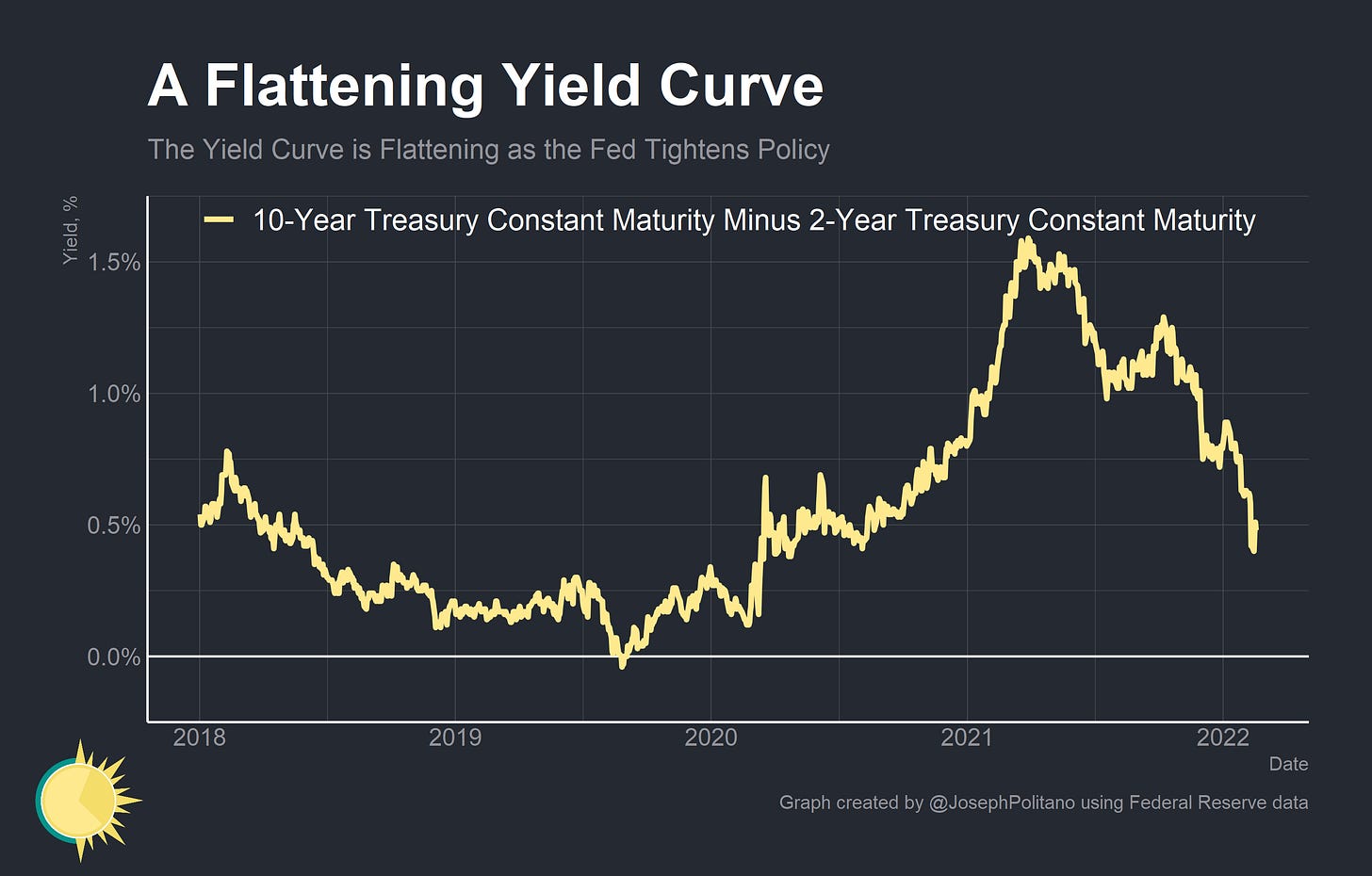

The big risk—as in all recent tightening cycles—is that the Federal Reserve goes too far the other direction. Recent policy signals have dramatically flattened the yield curve, raising short term interest rates but leaving longer-term interest rates little changed. Further moves could run the risk of a yield curve inversion—where yields on shorter-maturity treasury debt are higher than yields on longer-maturity debt. Inversions do not necessarily portend recessions as some believe (more on this in an upcoming blog post), but they can be an indicator that market participants think interest rates are too high and expect the Federal Reserve to lower rates in the near future. Ominously, the 1 year forward yield curve has already inverted.

Conclusions

The big cause—and casualty—of the Federal Reserve’s pivot has been the Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) policy framework that was instituted just before the pandemic. Instead of fighting inflation every time it exceeded 2%, FAIT allowed the FOMC to target 2% average inflation and thereby stimulate the economy further during downturns in order to hopefully avert the kind of low-growth recoveries that occurred after the 2008 recession.

The success of FAIT is that Jerome Powell was much more willing to fight the pandemic downturn than Ben Bernanke was to fight the 2008 downturn. The failures of FAIT were in the specifics. What timeframe was inflation supposed to average 2% over? What was the maximum inflation level that the Federal Reserve would tolerate? Is inflation supposed to go below 2% to compensate for periods above 2%? Expectations among financial market actors were incredibly muddled, and it is unclear what, if any, consensus there was within the FOMC about the specifics of FAIT. Functionally, it appears that policymakers at the Federal Reserve were taking a very ad-hoc view about their monetary policy strategies, balancing tradeoffs and making policy decisions on the spot. All this came together to create an unprecedented policy pivot.

Some of this policy volatility was inevitable. The pandemic has been both unprecedented and unpredictable, making monetary policymaking much more difficult than during “normal” times. FAIT is a new policy regime, and new policy regimes in all arenas are often built as skeletons that are filled in later as greater consensus is built and policy is “field-tested.” However, the core problem remains that the Federal Reserve, despite being a data-driven institution, has not been forthright enough about the data they are centering their policy decisions on. The FOMC believes they have made substantial progress towards their employment mandate, but employment remains below pre-pandemic levels. They believe that inflation is no longer transitory, but are coy about the data points that are driving their newfound inflation worries. The fact that outside observers have struggled to predict the path of monetary policy is not their failure, but a failure of policy communications. For the Federal Reserve to be effective, they have to pick clearer policy targets and get better at communicating their reaction function.