What are Americans Buying?

A Lot of Goods, and Different Goods than they were Buying Pre-Pandemic

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

A constant theme of the pandemic economy has been the reallocation of consumer demand from services to goods. Stuck at home and unable or unwilling to purchase services due to their higher COVID risk, consumers have spent record amounts on goods—particularly big-ticket durable goods. This elevated demand has driven a straining of supply chains and a rise in economy-wide inflation as producers attempt to meet the drastic shift in consumer preferences.

There has also been a radical change in consumer spending patterns within the goods sector—both in what goods Americans are buying and how they are buying them. Spending has shifted from in-person retail to e-commerce and from restaurants to grocery stores—but in both cases spending patterns are reverting to pre-pandemic trends as businesses and consumers adapt. Americans’ real consumption is also up in almost every goods sector—except in critical energy goods. These shifting spending patterns are especially important to analyze as they are driving much of the current outlook for inflation and economic growth.

Homebound Buyers

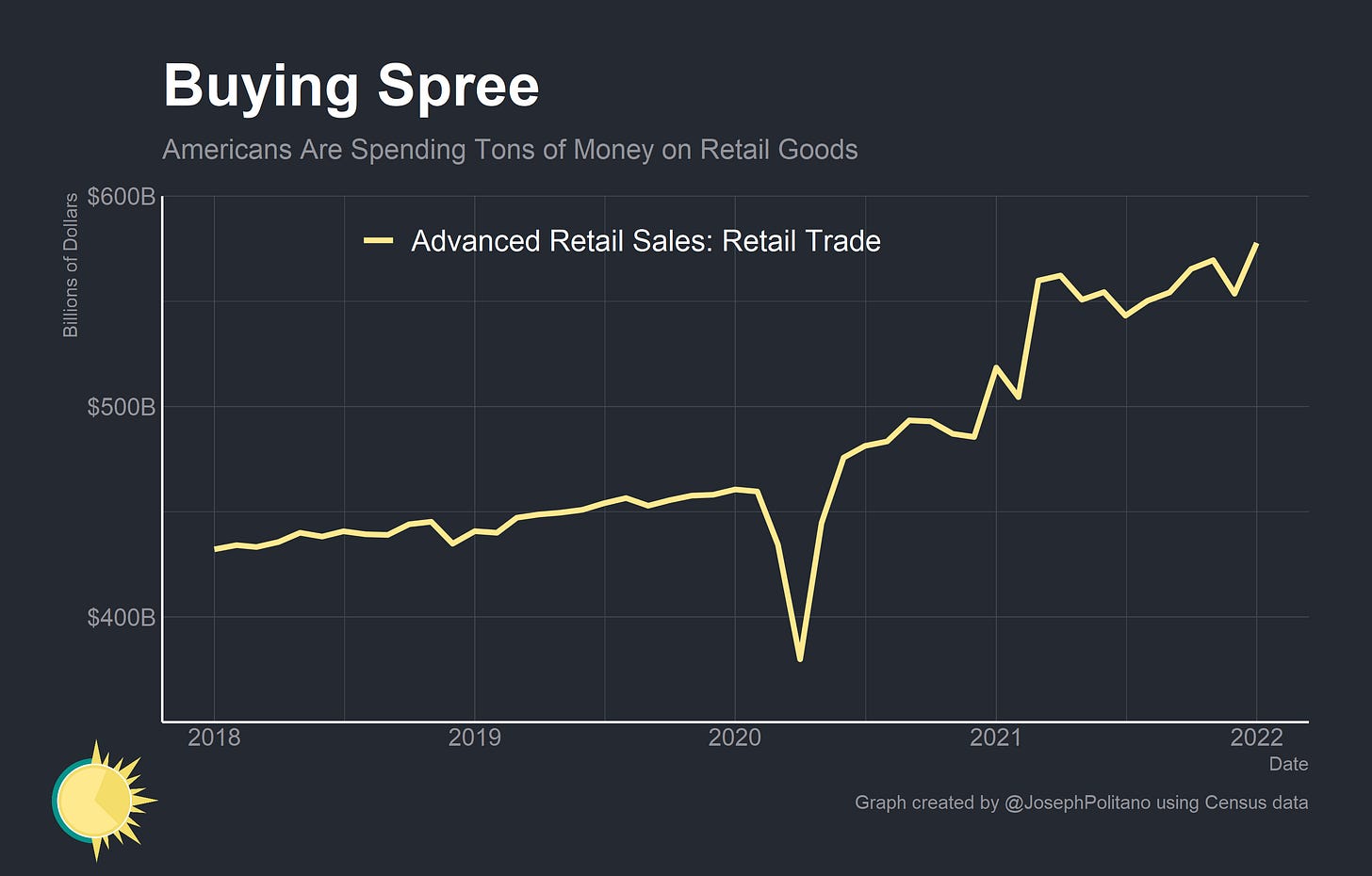

Retail trade sales plunged at the beginning of pandemic, only rebounding in June of 2020 after the initial shock of the pandemic wore off and household balance sheets were strengthened by fiscal stimulus. Spending remained only slightly above trend until early 2021, at which point it rocketed up nearly 10% and remained high for the duration of the year.

Unsurprisingly, spending at electronic shopping and mail-order houses (the verbose industry classification that includes e-commerce giants like Amazon) shot up as soon as pandemic lockdowns began. Keep in mind that this does not include all e-commerce orders, as digital purchases of goods from stores with physical retail locations are not counted here. More comprehensive data shows that at its peak in Q2 2020, nearly 16% of all retail sales were through e-commerce, though that number has since shrunk back down to only 13%. Interestingly, nominal e-commerce spending has not shrunk, it is only that offline spending has grown so much that online spending now constitutes a lower share of total spending.

Homebound consumers also spent significantly on residential improvements as the pandemic kept many of them inside for longer. Spending at buildings materials and supplies dealers is up $10B from its pre-pandemic level, and spending on furniture and other home furnishings is also highly elevated.

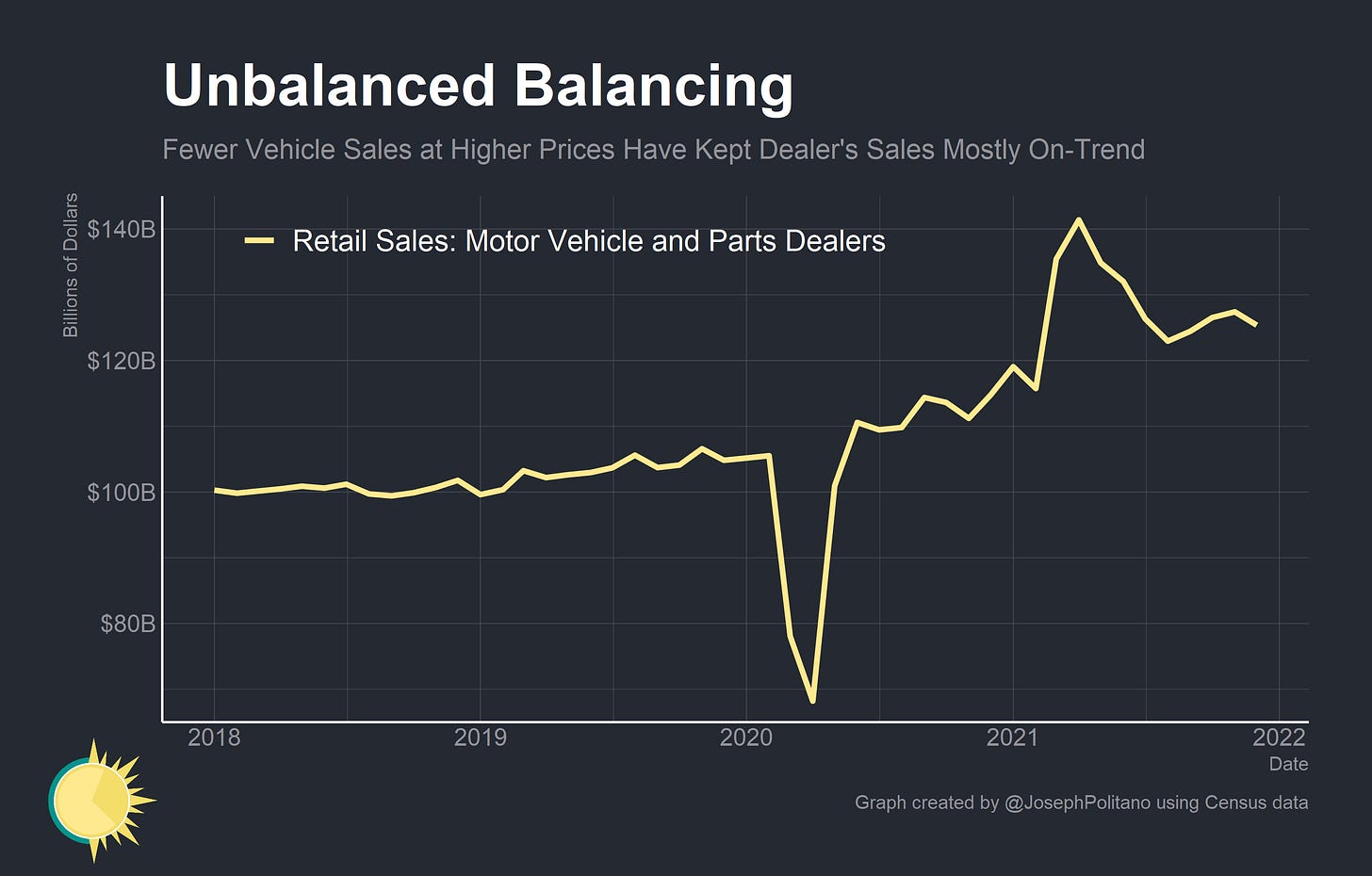

Durable goods have been the centerpiece of both the consumer spending and inflation story over the last year, and nowhere is that more true than in the motor vehicle industry. Interestingly, despite the prices of new and used motor vehicles significantly increasing since the start of the pandemic, retail sales at dealerships have not significantly increased. This is for a couple reasons—for one, total retail sales of used automobiles (which have increased in price by nearly 50% with nearly commensurate increases in sales numbers) are only 1/8 the size of retail sales of new automobiles (which have only increased in price by about 14%). For two, there simply are fewer new cars being sold due to supply chain and production issues. So despite significantly higher per-vehicle prices, sellers are not seeing extremely high revenue growth.

Food is the other major sector where consumer spending has involved in interesting ways. At the beginning of the pandemic Americans stopped spending at restaurants—total food service spending more than halved over the course of a few months—and spent more at grocery stores. That held true throughout 2020, but by spring 2021 spending at restaurants had fully rebounded and even exceeded the pre-pandemic level. Americans are back to spending more on restaurants than on grocery stores, and they are also spending much more on food in general. Some of this comes from inflation—price growth in the food sector has been about as large as average inflation—but a lot of it comes from shut-in consumers increasing their real consumption of food.

If you haven’s subscribed, consider signing up to get free economics news and analysis every Saturday morning!

The Real and the Nominal

Indeed, nominal spending alone represents only half the puzzle—real consumption has been also fluctuating dramatically since the start of the pandemic. Let’s take food as the first example—nominal spending on food for off-premises consumption (which largely consists of groceries) is up more than 20%, but real consumption is also up more than 10%. Considering that real food service spending (which largely consists of restaurant spending) is basically at 2020 levels, it is likely that Americans are consuming significantly more food than they were pre-pandemic. Keep in mind that this doesn’t literally mean eating more calories, as a shift into higher-quality items would classify as higher real consumption.

Durable goods are another sector with a major divergence between nominal and real spending. Durable goods prices have grown significantly over the last year, contributing to the spike in inflation—but it is also true that Americans are consuming more durables than ever before. Of the three largest categories within durable goods, real consumption is above pre-pandemic levels by 15% for motor vehicles, 18% for furnishings and other household equipment, and nearly 37% for recreational goods and vehicles. Even categories like jewelry and musical instruments have seen real consumption grow 33% and 20% from their 2019 levels, respectively.

One area where Americans really aren’t seeing a major rise in real consumption is gasoline—despite spending on gas being 20% above pre-pandemic levels. Nominal outlays have basically doubled from their 2020 lows, but real consumption only recovered to its pre-pandemic level. Since fuel demand is inelastic in the short term (drivers rarely change travel patterns depending on the price of gasoline), it is not likely that real consumption will shrink given higher prices. On the flip side, oil producers have restrained production given the higher risks associated with the volatility in pandemic-era energy markets, something that is only changing slowly as prices climb.

Conclusions

Despite the setbacks caused by Omicron, it is clear that the demand reallocation that occurred at the beginning of the pandemic is beginning to unwind. Total goods spending has only inched upward since the second half of 2021 while services spending rapidly approaches the pre-pandemic trend. Still, there are a few key trends to watch out for as the pandemic continues to abate.

The first is the long-term trajectory of the goods-services balance in spending patterns. While it is likely that rebalancing mostly occurs, it is possible that the spending decomposition will not return precisely to its pre-pandemic state. Consumer lifestyle structure and preferences have changed drastically after two years of COVID, and it is possible that people will continue to spend more on at-home goods and less on in-person services even when the virus has less impact on their lives.

The second is the within-goods breakdown of real and nominal consumption. The highly elevated durable goods consumption may not be sustainable in the long term—after all, there are only so many pieces of furniture to fit in a house—and so it is possible that nondurable goods will regain significant share of total retail spending. Additionally, real consumption of goods with supply chain issues (namely, cars) will likely remain strong as consumers “make up” for foregone purchases.

The last key trend is in aggregate spending. It remains above the pre-pandemic trend, partially causing the spike in inflation that has occurred over the past year. Policymakers at the Federal Reserve are likely keen on cooling the rate of nominal spending growth in order to combat inflation, so it will be critical to monitor retail sales data in order to evaluate the success of monetary policy in managing prices and growth.