What's Going on With Wages?

Diving into the Data to Analyze America's Rapid Wage Growth and So-Called "Wage Inflation"

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

America’s labor market is rapidly tightening as the economy heats up and employers begin fiercely competing for workers. With the tightening labor market has come extremely high wage growth, especially for lower-pay service-sector workers. While strong wage growth has been a boon for many employees, some economists and public figures worry that wage growth is so high that it could start pushing up inflation.

Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon said "there is real wage inflation everywhere." Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers said that “It’s hard for me to see wage inflation subsiding or price inflation approaching 2 percent at current, let alone future, wage inflation rates.” Even Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has started to publicly worry about that the pace of wage growth could start contributing to inflation.

To understand today’s record wage growth—and whether it is sustainable—requires an in-depth examination of the data on labor costs. It also requires digging beneath the surface to examine how wage growth is manifesting across industries, occupations, genders, and income levels. Today’s labor market is extremely progressive, with lower-income workers enjoying the fastest wage growth of any group. Wage growth is also only a problem to the extent that it has occurred before the economy reaches full employment, indicating the extreme negative impact of COVID on the economic recovery.

Understanding ECI

The Employment Cost Index (ECI) is an extremely underappreciated set of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). In the same way that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) attempts to measure the costs for consumers to purchase goods and services, the ECI attempts to measure the costs for employers to purchase labor.

Why is this so important? Well, many other measures of wages and compensation fall victim to issues stemming from extreme composition bias. Take the average hourly earnings measures published monthly alongside the jobs report: since they only measure average earnings of employed workers, changes in the composition of employed workers can radically affect measurements. When millions of low-income workers were laid off at the start of the pandemic average hourly earnings rocketed upwards, and when these low-income workers were re-hired average hourly earnings were pulled downwards. The ECI accounts for this bias by holding the composition of industries and occupations surveyed constant, so the index accurately measures changes in wages regardless of changes in employment. ECI also allows for robust measurement of changes in wage level within different industries and occupations.

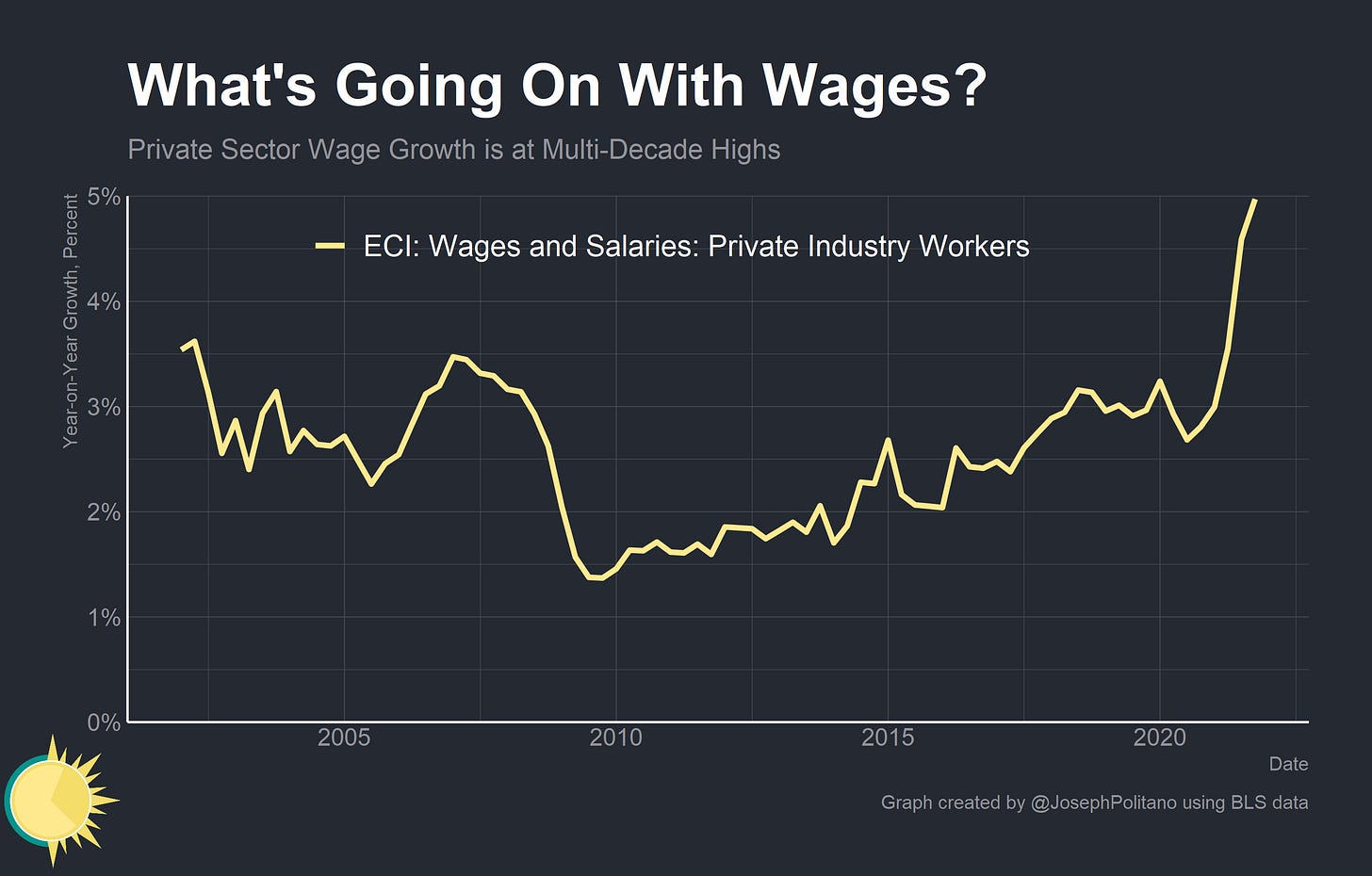

If we look at last quarter’s ECI data, private industry wage growth is at its highest levels in decades. It’s important to look at private sector wages first, as public-sector wages are less sensitive to demand, usually move slower, increase at more regular intervals, and are often indexed to inflation. Private industry wage growth was a whopping 5% over the last year, significantly higher than the pre-COVID 3% annual growth rate.

Looking at total compensation for all civilian workers makes the jump look less strong relative to the pre-Great Recession economy, but still strong relative to the pre-COVID economy. Examining total compensation is always important in order to get a full picture of worker pay (as approximately 1/3 of all compensation is not given as wages or salaries), but it is worth noting that wages tend to be the leading indicator. The primary drivers of the gap between total compensation of all civilians and private industry wages are relatively slow aggregate benefit growth and relatively weak public sector wage growth. However, we must dig below the aggregate totals to examine wage growth by industry and occupation in order to fully understand the situation.

A Tightening Labor Market

A large chunk of above-trend wage growth comes from rising pay for production/service employees—against a backdrop of constant wage growth in traditionally higher-paid jobs1. Keep in mind that lower-income workers are less likely to receive substantial benefits, so high wage growth among low-income workers helps explain some of the discrepancy between private sector wage and compensation growth.

The effects of tight labor markets become evident when you look at median wage growth by wage level. Incomes for workers in the 1st quartile (the lowest-wage workers) are growing the fastest, which was also the case in the relatively tight labor markets of the late 1990s and late 2010s. Strong labor demand helps these workers the most, and that is exactly what we are seeing today.

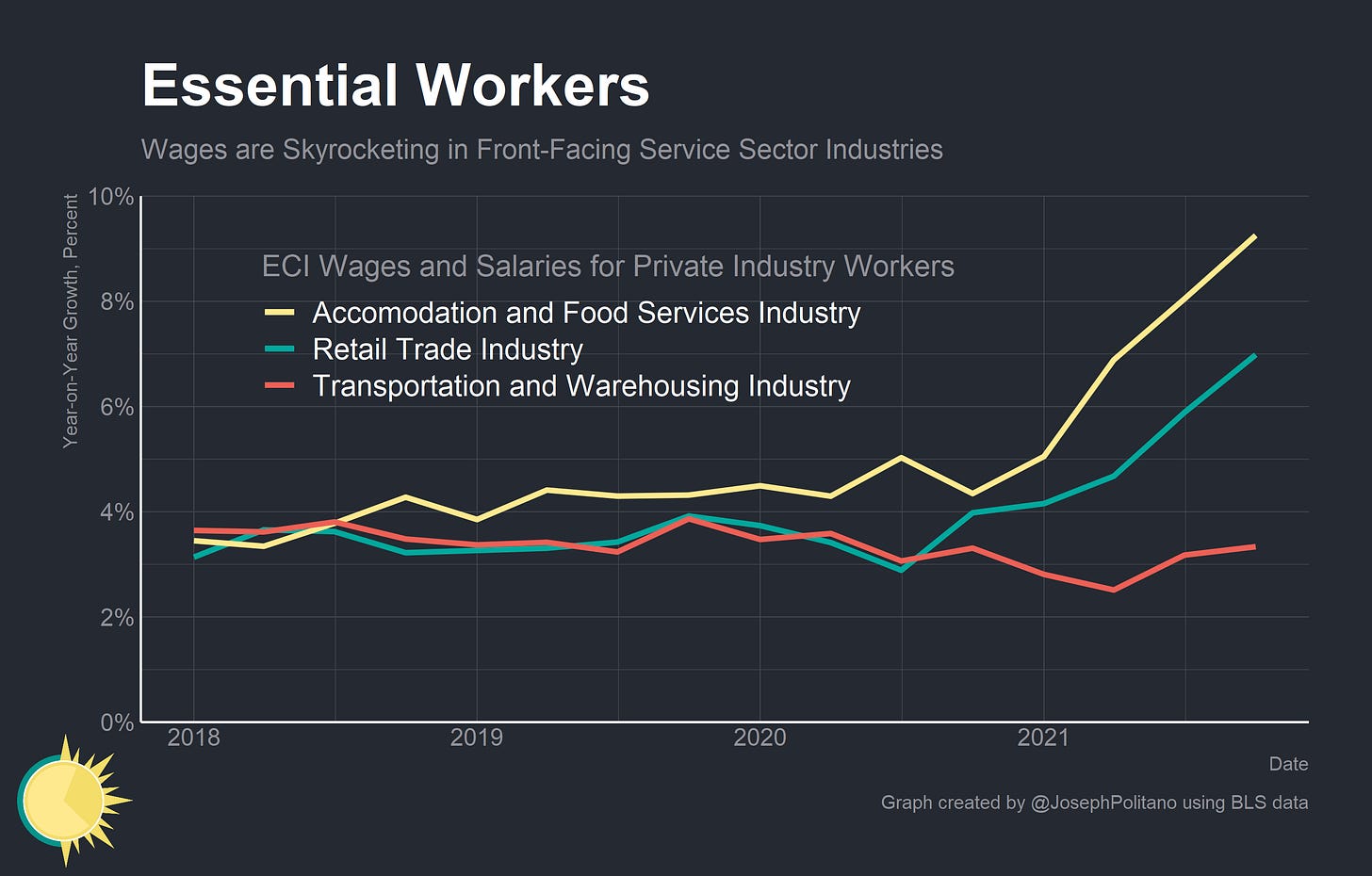

Examining wage growth by industry also shows how strong labor demand is benefitting low-wage workers—and reveals the outsized impact of the pandemic. Firstly, wage growth in the accommodation & food service and retail trade industries is extremely high. Since these industries tend to be relatively low-paying, the high wage growth is accruing to low-income workers. Second, wage growth is lower in the (admittedly already higher paying) transportation and warehousing industry. Part of this is likely due to the increased risks of in-person consumer-facing service sector employment during the pandemic. Workers are demanding more pay in order to be compensated for these risks, and many workers are instead shifting to jobs with less in-person contact (employment in transportation and warehousing has fully recovered while employment in retail trade & food service and accommodation has not).

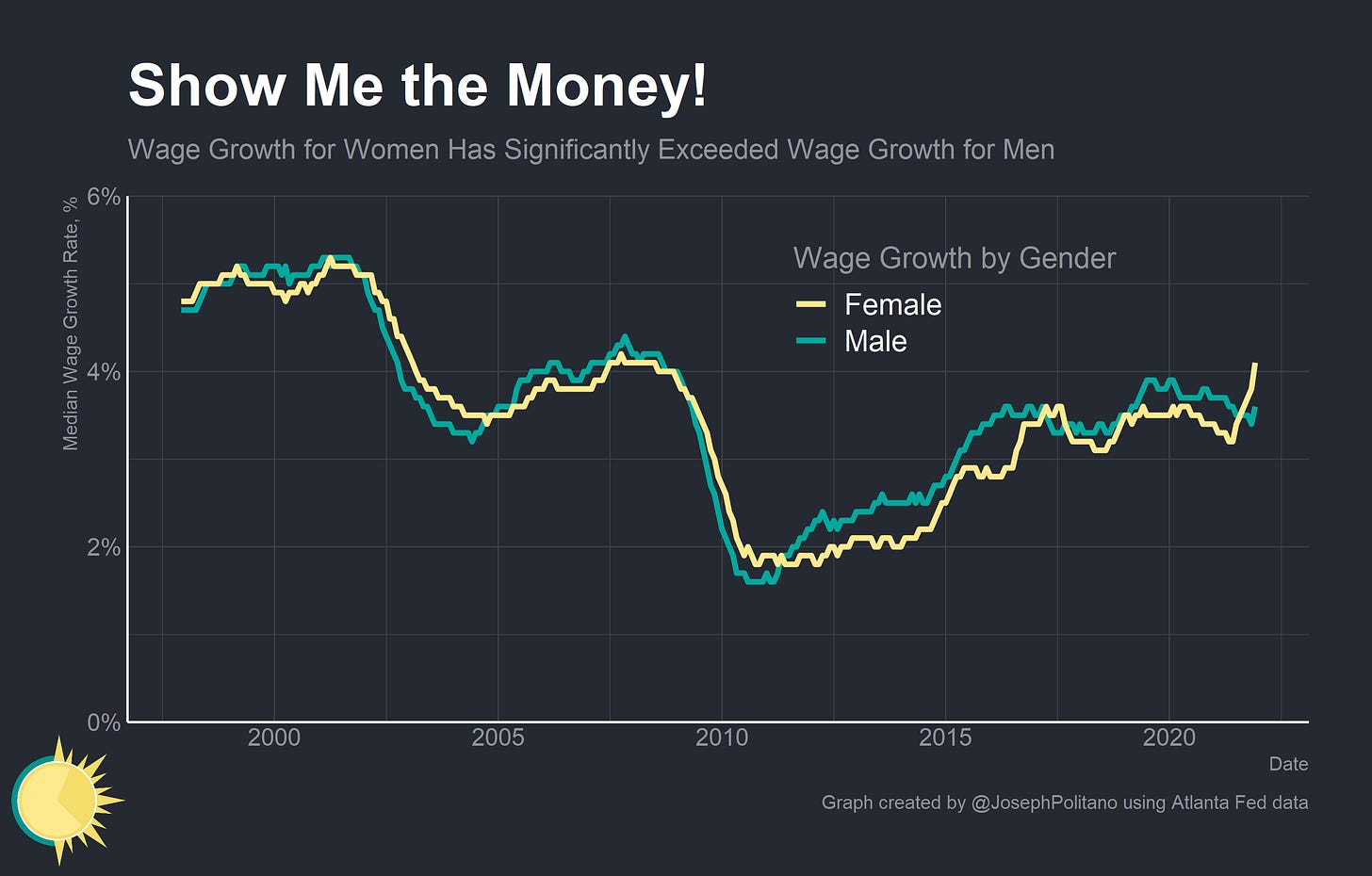

Finally, the strong labor demand is affecting different groups of workers differently. For the first time, wages for women are increasing significantly faster than wages for men. This is likely due to service sector workers and lower-income workers—both of which are disproportionately female—experiencing faster wage growth. Wages are also growing faster for high school graduates than for bachelor’s or associate’s degree holders. The strong labor demand is helping to reverse the recent trend in American economic history where the vast majority of wage increases accrued to a limited number of high-income, well-educated workers2. But could wage growth be too strong—driving inflation instead of real economic growth?

Wages and Inflation

Private industry wages overshot their pre-COVID 3% annual growth trend in 2021, instead growing at a 4% annual rate over the last two years. Obviously, there is an upper limit to nominal wage growth before it simply contributes to rising prices—and it seems like the Federal Reserve is worried that we may be approaching that point. Here’s an excerpt from Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s December press conference (I know it is long, but I promise it is worth the read):

So coming to your real question, we got the ECI reading on the eve of the November meeting—it was the Friday before the November meeting—and it was very high, 5.7 percent reading for the employment compensation index for the third quarter, not annualized, for the third quarter, just before the meeting. And I thought for a second there whether we—whether we should increase our taper, [We] decided to go ahead with what we had—what we had “socialized.” Then, right after that, we got the next Friday after the meeting, two days after the meeting, we got a very strong employment report and, you know, revisions to prior readings and, and no increase in labor supply. And the Friday after that, we got the CPI, which was a very hot, high reading. And I, honestly, at that point, really decided that I thought we needed to—we needed to look at, at speeding up the taper.

…..

Jeanna Smialek: If I could just follow up quickly, you noted that the ECI was one of the things that made you nervous, but you also said earlier that you don’t see signs that wages are actually factoring into inflation yet. And I guess I wonder how you think about sort of the wage picture as, as you’re making these assessments.

Chair Powell: Right. So—but I said—you, you quoted me correctly. It’s, it’s—so far, we don’t see—wages are not a big part of the high-inflation story that we’re seeing. As you look forward, let’s assume that the goods economy does sort itself out, and supply chains get working again, and maybe there’s a rebalancing back to services and all that kind of thing. But what, what that leaves behind is the other things that can lead to persistent inflation. In particular—we don’t see this yet, but if you had something where wages were persistently—[increases in] real wages were persistently above productivity growth, that puts upward pressure on, on firms, and they raise prices. It would take something that was persistent and material for that to happen. And we don’t see that yet. But with the kind of hot labor market readings—wages we’re seeing, it’s something that we’re—that we’re watching.

So to condense all of that down: the Federal Reserve doesn’t see wages driving current inflation, but they are increasingly worried that wages could be rising too fast and start driving inflation in the near future. This is likely part of what is behind their hawkish pivot in recent months—but should they really be worried?

Long-time Apricitas readers will know that I support nominal income targeting, in particular Gross Labor Income targeting. Such a system would have the Federal Reserve directly target aggregate growth in labor income instead of inflation. This would still keep inflation in check (as constant nominal income growth cannot support accelerating price growth), but it would also prevent the kind of aggregate demand collapses that caused the Great Recession. The chart above estimates gross labor income using three separate methodologies: first by simply taking the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s measure of total employee compensation, second by multiplying the BLS’s non-farm payrolls data by average wages and average hours, and finally by multiplying ECI’s private wages & salaries measure by the prime age employment-population ratio. If you want to read more about these methodologies go here, but the important thing to note is that the ECI method is the most accurate and predictive.

In aggregate, nominal incomes are on trend and all measures of gross labor income should be on or above trend in the near future. That alone is not a problem for the Federal Reserve—indeed, it is actually emblematic of its success in fighting the economic downturn. However, the composition of aggregate income is a problem for Jerome Powell.

We are experiencing record high wage growth despite employment remaining below pre-pandemic levels and well below “full employment.” Despite high aggregate demand, a large number of workers are unable to rejoin the workforce because of elevated COVID risks and a large decrease in demand in certain service sectors (like entertainment, tourism, and nursing care). Childcare issues and sickness are keeping workers off the job, and as a result nominal growth is manifesting as higher wages instead of faster employment growth.

Still, it is worth remembering that sustainable high wage growth is possible and should be a policy goal. Wages and salaries for private industry workers have grown at a 4% annualized rate over the last two years—which would be perfectly consistent with a 4% gross labor income target if the economy was at full employment. Indeed, at full employment wage growth could likely hit the 4.5% mark without causing issue as labor could increase its share of national income and real GDP could return to its historical 2.2% annual growth rate. Of course, policies to increase long-run real GDP growth would also allow for additional increases in real wages. The key for the Federal Reserve is to keep nominal demand strong in order to keep up robust wage and employment growth, and the key for other policymakers is to get COVID under control so that the pandemic is no longer weighing on the labor market recovery.

Incentive pay, mostly from the credit intermediation industry (banking and other related services) has pushed up ECI’s wages and salaries measures recently. Incentive pay is extremely volatile and therefore usually best excluded to measure “core” wages, but even including incentive pay wages for management, business, and financial occupations is growing much slower than wages for service or production employees.

Whenever I bring up robust nominal wage growth, someone invariably comments that high inflation means that real wages are down. First, real wages have not decreased or increased substantially since the start of the pandemic. Second, prices are much more volatile than wages—so nominal wage growth is more “sticky” than price growth. In other words, pay raises are likely here to stay even as some prices decrease. Finally, it is always bad practice to estimate real wages over such a short time frame, as this Employ America piece explains better than I could.

Just a note: the "historical" 2.2% real output growth, is only "historical" for the 10 yrs post Great Recession. For the 30 yrs prior to that, the "historical" real growth was 3.3%

OK. Per Capita RGDP. Still, the "history" is long but prior to the GR. More recently it was trying to return to trend...

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/from-the-title-the-fed-could-have