Why Are Gas Prices So High?

Capital Discipline, OPEC, Russia, and More

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

Gas prices have jumped nearly 20% in the last month, nearly 50% in the last year, and more than 100% from their mid-2020 lows. In nominal terms, gas prices have never been so high. Given the importance of petroleum products as transportation fuel, electricity sources, and manufacturing inputs, the rising price of oil has immense macroeconomic and geopolitical importance. So why are gas prices so high?

In short: a surplus of demand and a shortage of supply—but people who watch oil markets professionally know that things are rarely so simple. A combination of restrained growth from US producers, lower Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC+) targets (that the group has still failed to meet), the loss of significant Russian energy supplies, and a rapidly-rebounding global economy has sent crude prices through the roof. The radical shift in domestic US oil production dynamics is perhaps the most important change in the post-pandemic oil market—US shale’s position as a competitive, marginal producer of oil supported low prices throughout the latter half of the 2010s and isn’t doing so now.

OPEC+’s decisions are a matter of geopolitics and oligopolistic self-interest—financial and strategic planning designed to maximize returns and political clout for its members (to the extent that they work together). The Russia shock is nearly all geopolitics—a combination of producers pulling out and consumers looking elsewhere due to sanctions and political risk in the fallout of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But the radical shift in domestic production behavior is more about economics, and understanding why American oil companies have changed their response function is critical to understanding why gas prices are so high. Combined, these factors have merged to create the perfect storm that has sent gas prices higher and higher.

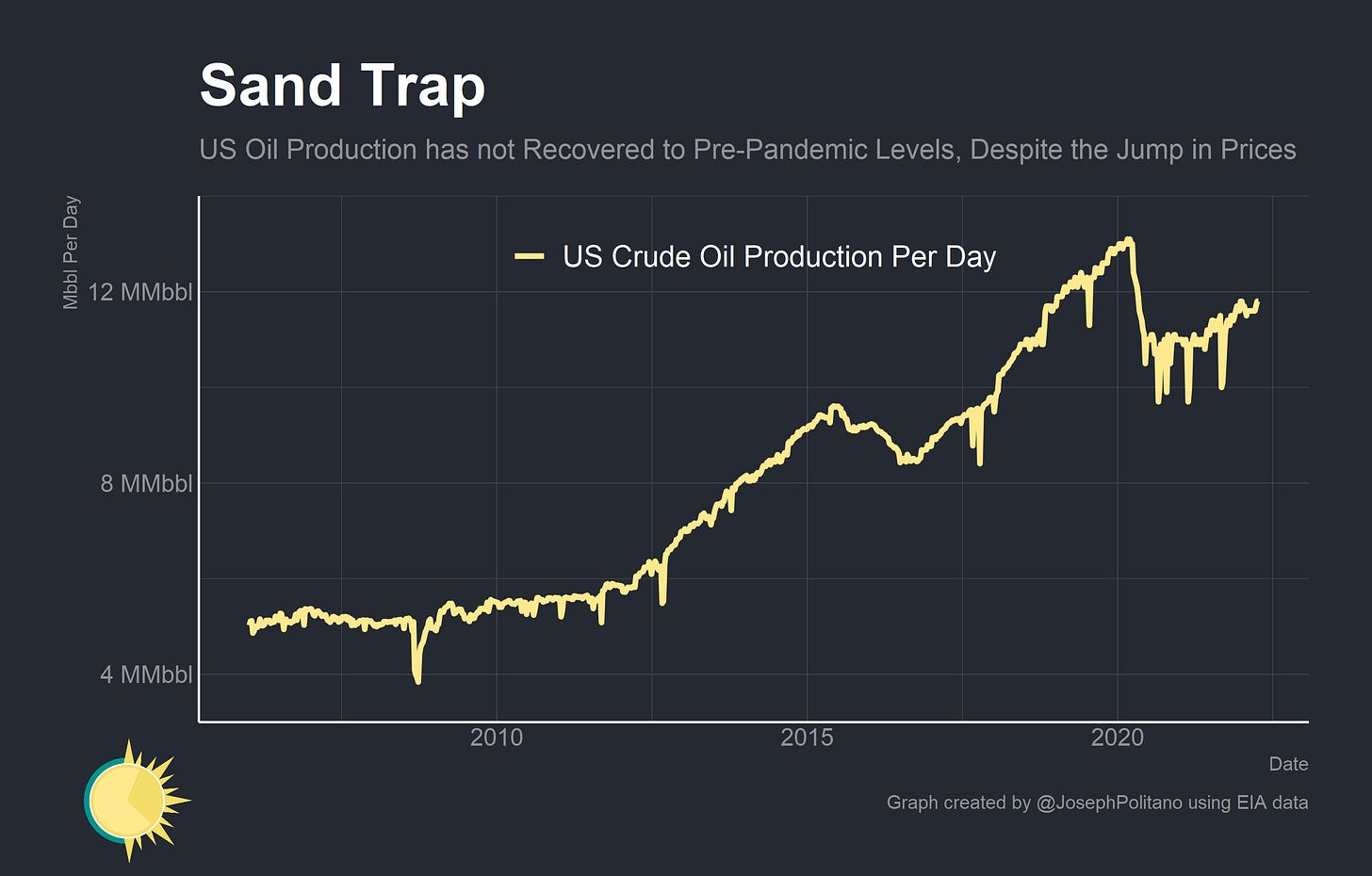

Sand Trap

For more than a decade, US oil production has been growing at breakneck speeds as the shale revolution allowed America to become the world’s largest oil producer. Even the 2014 oil price crash—which wreaked havoc on the economies of many large oil producing nations—barely interrupted the rapid growth of US oil output in the long run. American oil was nowhere near as as cheap to produce as, say, Saudi oil—but the competitive nature of the US oil market made it the marginal supplier for the entire globe. If prices went up, American shale would increase production and keep costs contained. If prices went down, American shale would be forced to pare back unprofitable drilling until prices rose again.

From basically 2012 to 2020, US oil investment followed a fairly consistent pattern; when prices went up, so too did drilling and vice versa. The post-2014 oil market saw a lot less drilling thanks to some of the lowest prices since the depths of the 2008 recession, but American production was still fairly strong. Then, the entire relationship broke down after the onset of the COVID pandemic. Crude oil futures briefly went negative (remember that story?) as global oil demand fell off a cliff. Meanwhile, Russia decided it would not agree to Saudi-devised production cuts and effectively ruined the working arrangement within OPEC+—leading to a massive Saudi-Russian price war that kept crude oil trading at low levels (the price war was eventually resolved when Russia agreed to production cuts). In the aftermath, American oil companies were far less willing to invest in new production—and domestic output has still not fully recovered despite oil prices hovering at nearly twice pre-pandemic levels.

The phrase of the day in the oil industry became “capital discipline”—a catch-all term for policies that kept production low even in the face of higher prices. In the most recent Dallas Fed Energy Survey, 59% of oil and gas executives cited capital discipline as the primary reason why publicly traded oil companies are restraining growth despite high prices. Many small companies were forced to fold, restructure, or be bought out by oil majors just to survive the 2020 crash—often under harsh terms or with restrictive debt covenants. Oil majors were under increasing pressure from shareholders to pare back investment dramatically in order to recoup losses. The result was a dramatic shift in behavior throughout the US oil market.

But why did investors and lenders suddenly shift so hard into capital discipline? For one, an incredible amount of uncertainty still pervades the oil market—it is not healthy when crude prices can swing up and down 10% in a matter of days due to virus-related and war-related risks. But perhaps more importantly, and despite the decade-long growth in US oil output, shareholders have barely made any money on the US oil boom. XOP—the SPDR Oil and Gas Exploration and Production ETF—has just barely netted a positive return since its inception in mid 2006. The 2014 and 2020 oil crashed wiped out billions of dollars in wealth and shareholders blamed overproduction. Capital discipline was designed to ensure that another crash wouldn’t happen.

Looking at profits for the broader US petroleum and coal industries, it becomes clear just how bad the post-2015 market has been. The US fossil fuel industry has been in the red for nearly 7 years at this point—and has only recently clawed its way into the black. The boom-and-bust rollercoaster hasn’t been profitable for American oil producers, so they’re rationally trying their hardest not to get caught in another crash.

OPEC and Friends

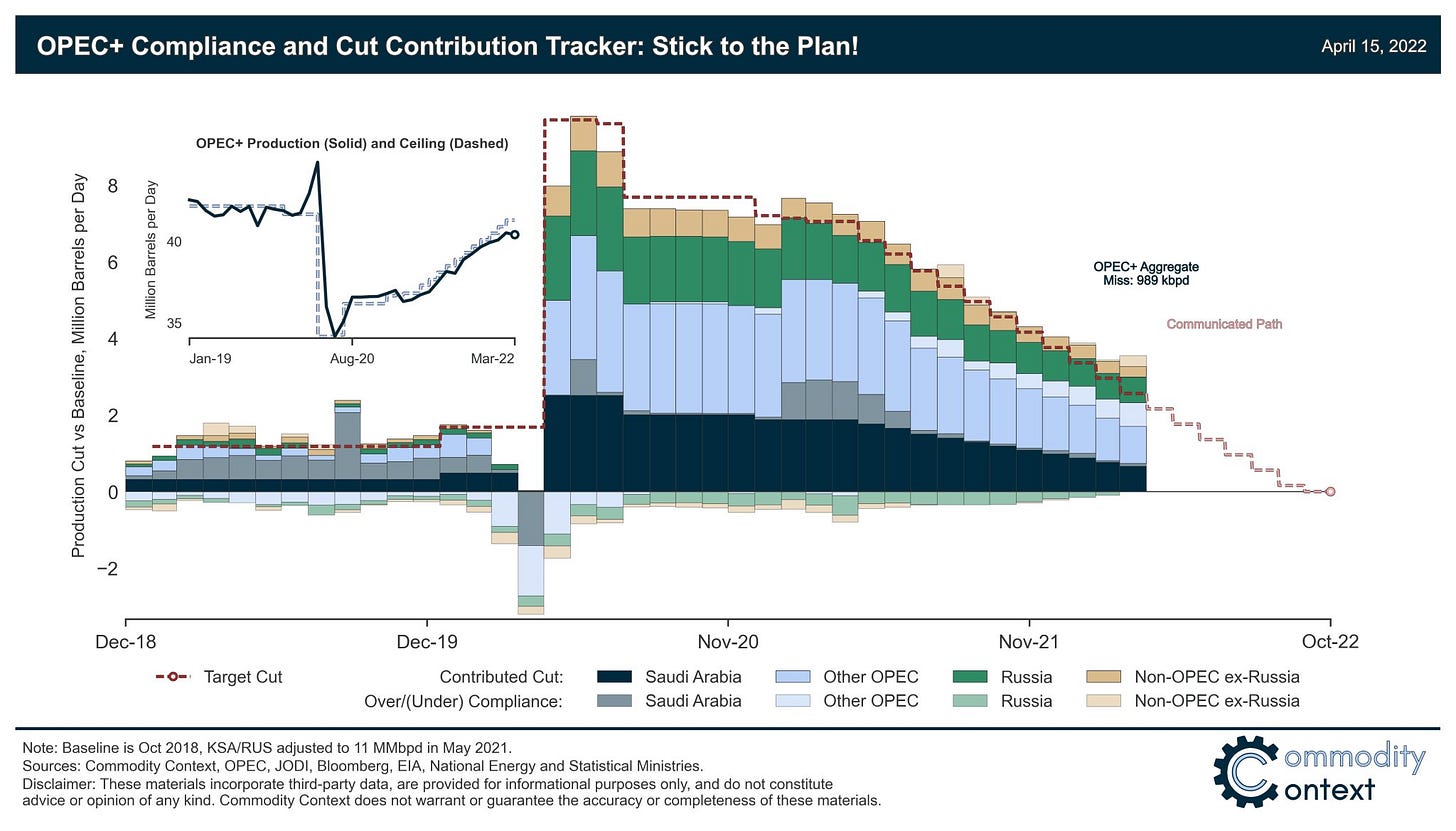

Oil production outside the US hasn’t exactly been stellar either as analysis from friend-of-the-newsletter Rory Johnston of Commodity Context shows. OPEC+ was ever-so-slowly unwinding their pandemic-era production cuts before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but were having significant difficulties even meeting these lower obligations. OPEC+ as a whole is underproducing its own targets by nearly a million barrels per day—and Russia was the only major country overshooting its targets.

Then, of course, came the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Russia is the second largest oil producer in the world, and much of Western Europe is dependent on Russian natural gas. Although sanctions from the European Union have excluded Russian energy, major producers are pulling out of the country, input materials are harder to import, and many countries are less willing to take Russian exports. Ural crude is trading at a $25 discount to Brent crude, indicating the extreme difficulty Russia is having in selling its oil. The country may be running out of storage capacity and willing buyers—especially as the European Union debates cutting itself off from Russian fossil fuels. Russia remains a source of extreme uncertainty and a significant shock to global oil supply.

Dancing Demand

On the flipside of supply, domestic US oil demand remains extremely strong—total American consumption is actually ahead of pre-pandemic levels. That’s partially because Americans are driving just as much as they were before the pandemic—despite the increase in telework. Only about 10% of American workers teleworked at any point in March, and the jury is out on whether teleworkers actually drive less than commuters. Telecommuters might commute less, but they can take several small car trips in place of their daily commute and may move to areas that are farther from city centers than regular commuters. The other reason that oil demand is so strong is that goods demand remains robust and oil is an important input material in many manufactured products.

China is experiencing the exact opposite situation as America: a rapid drop in oil demand. Recent COVID outbreaks in the country have been met with strict lockdowns from the Chinese government, and the resulting decline in mobility and consumption is perhaps the only thing keeping a lit on global oil prices. Chinese imports have fallen off a cliff recently, and a lot of that import reduction is coming from a collapse in domestic Chinese fossil fuel demand. The knock-on effects of the shutdown will likely have adverse impacts on the global economy in the long-run, but for right now the rest of the world is benefitting from the drop in Chinese demand.

Conclusions

In March, retail spending at gas stations crossed $63B, the highest on record. As a share of total retail spending it hit nearly 11%, higher than at any point in the last seven years. Though gasoline represents a smaller share of total consumer spending than in previous decades, it still represents a good chunk of low-income workers’ budgets. So what should we do?

For one, there are reasons to be optimistic that production will continue to ramp up outside of Russia. That same Dallas Fed Energy survey also showed the strongest reading for the of quarter-on-quarter business activity and capital expenditure diffusion indexes since the survey started in 2016. Rig counts and refinery capacity utilization are both growing at a brisk pace now. The number of permits issued for drilling in the Permian Basin just hit a new record high. The administration’s decision to release 180 million barrels from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve should help bridge consumption to a point where more domestic and foreign output can come online.

But the counterproductive policies have to be thrown out. Suspending gas taxes or issuing cash to drivers based on the number of cars they own may be politically popular but they don’t solve the core problem of the energy shortage. In fact, they only make the shortage worse by subsidizing gasoline consumption and doling out more money to the wealthier households who consume more gas but nevertheless have a better ability to absorb higher prices. Closing nuclear reactors in the middle of an energy crisis—as Germany, New York, and others have done—is short-sighted considering how much cleaner nuclear power is compared to fossil fuel. The implementation of the Department of Energy’s Civil Nuclear Credit Program should help bolster the US’s existing nuclear fleet, but we should work to prevent as many closures as possible while investing in next-generation reactors.

Fundamentally, oil remains a critical input to human society and the global economy. But it is a toxic one—millions of people die every year from emissions exposure and millions more will die from the adverse effects of climate change. The world needs to make serious efforts to reduce its dependence on oil, but if decarbonization is done in a haphazard way it will be impossible to maintain the political will to get through the climate transition. Economists nearly universally agree that carbon taxes and gas taxes are extremely effective climate policies, but the efforts from state governments across the political spectrum to suspend gas taxes in the face of today’s energy shortage underscore the political fragility of those policies. We can’t have green energy policy without green energy investment, and that means getting serious about solving today’s energy crisis.