America's $1T AI Gamble

US AI-Related Investment Keeps Breaking Records, With Total Software, Computer, & Data Center Spending Now Exceeding $1T Per Year

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing, you’ll join over 75,000 people who read Apricitas!

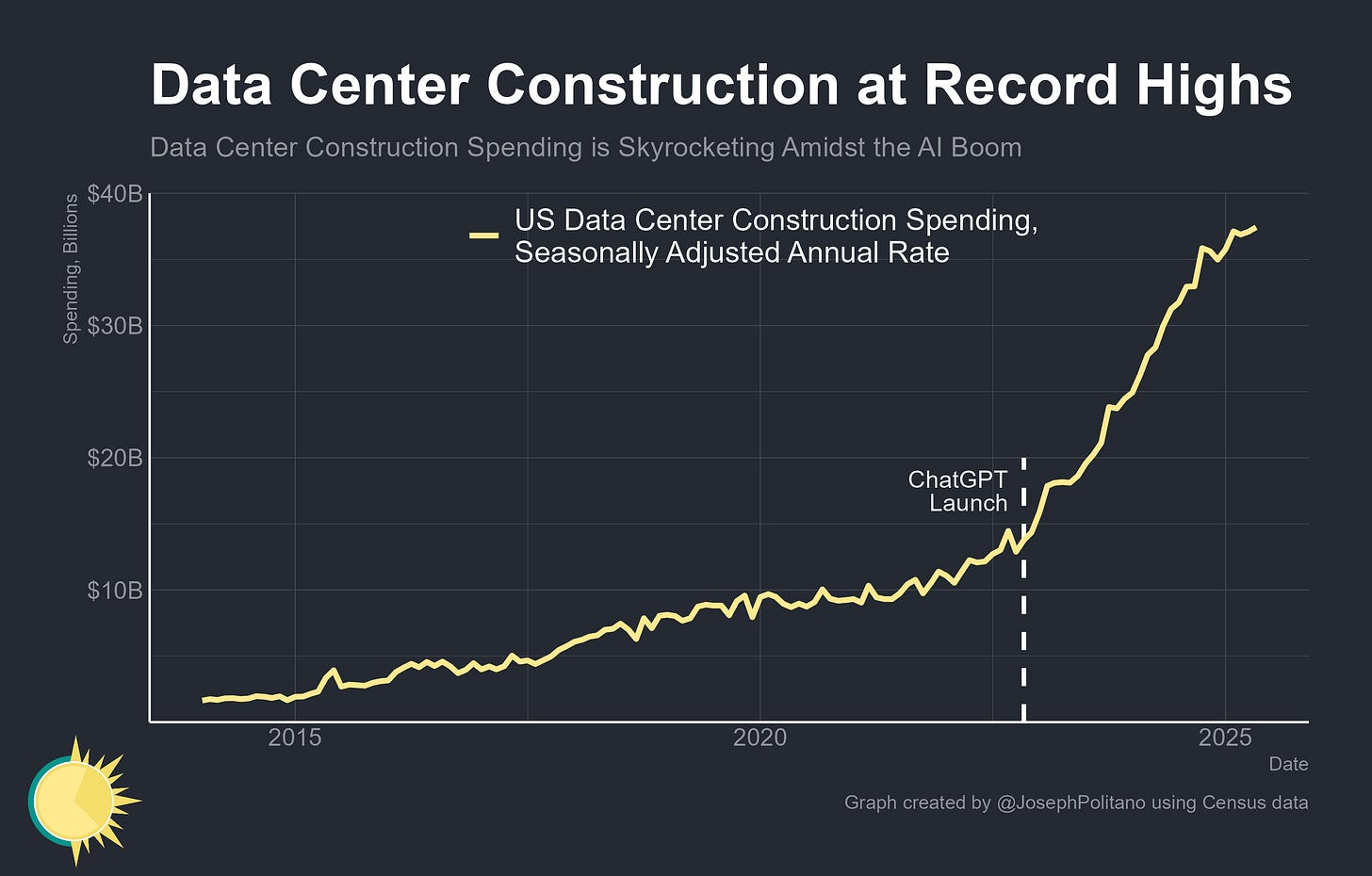

The United States is undertaking a historically unprecedented investment boom to build the computers, data centers, and other physical infrastructure needed to train and deploy Artificial Intelligence. Hundreds of billions of dollars have already been spent by hyperscalers racing to build smarter AI systems, and investment from major tech companies is set to shatter all previous records again this year. Amidst this boom, spending on data center construction has hit a new record high, now exceeding a $42B annualized pace, a more than 300% increase since the launch of ChatGPT in late 2022. While growth has slowed over the last six months, investment is still up more than 18% over the last year alone.

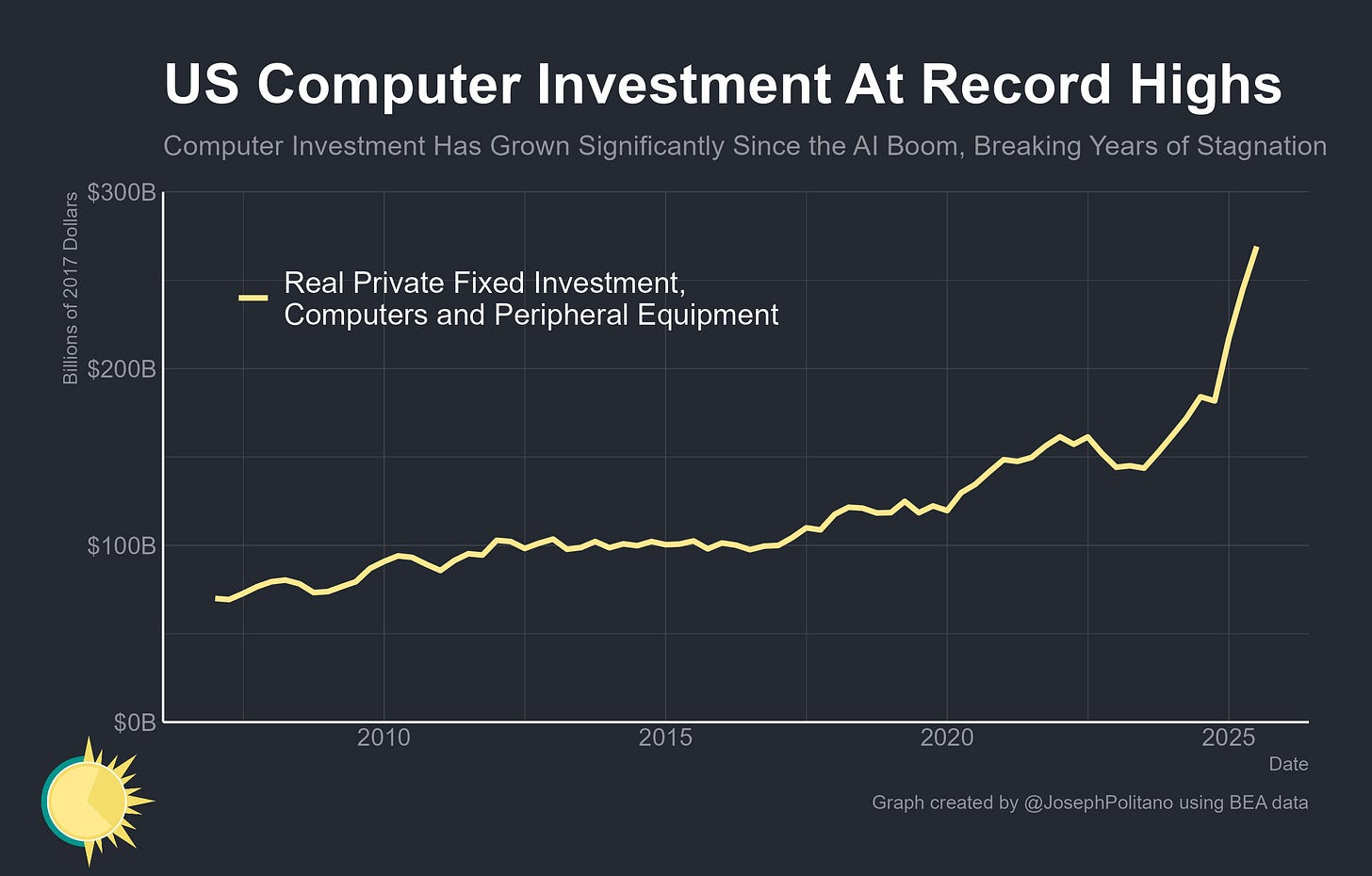

Yet that figure only reflects the costs to build data center facilities themselves, not the much larger costs of the expensive GPUs, TPUs, and other electronics housed within. Real US fixed investment in those computers and related peripheral equipment has surged to a record high of more than $270B annualized, up nearly 50% over the last year and up 77% since ChatGPT’s launch.

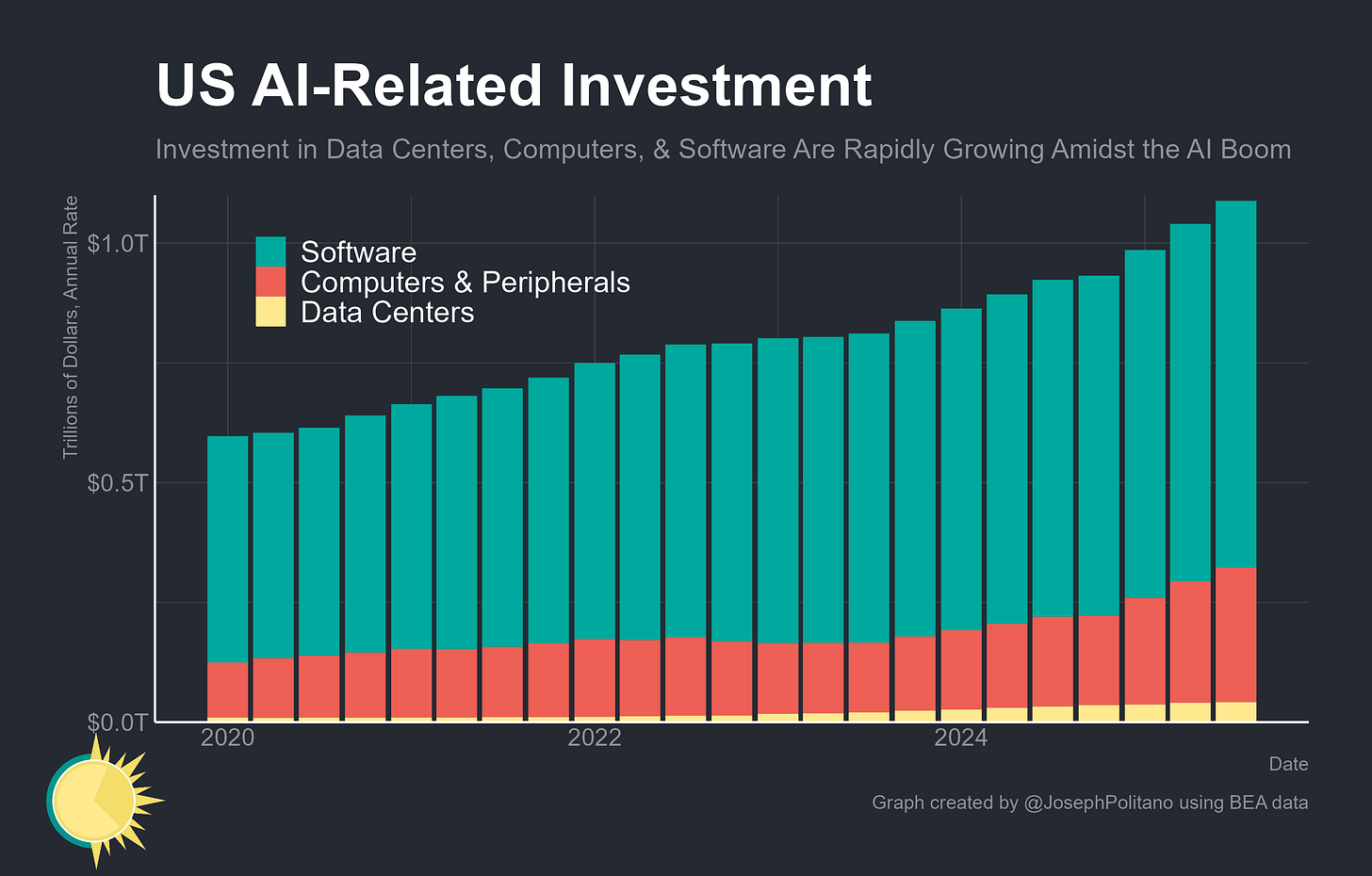

Likewise, spending on computers is dwarfed by investment in software development, which now exceeds $750B annualized, with an increasingly large share focused on training, deploying, and integrating AI systems. Combined, spending on data center, computer, & software investment now exceeds $1T annualized and is roughly equivalent to 3.5% of US GDP, another record high. This is also likely an undercount of the true value of AI-related fixed investment, as official statistics have a difficult time accounting for spending on computer parts or properly capturing all software development. Still, spending on data center facilities now rivals total office construction, spending on computers now exceeds all factory building, and spending on software investment now dwarfs new home construction. Across nearly all dimensions, investment in AI systems continues breaking records.

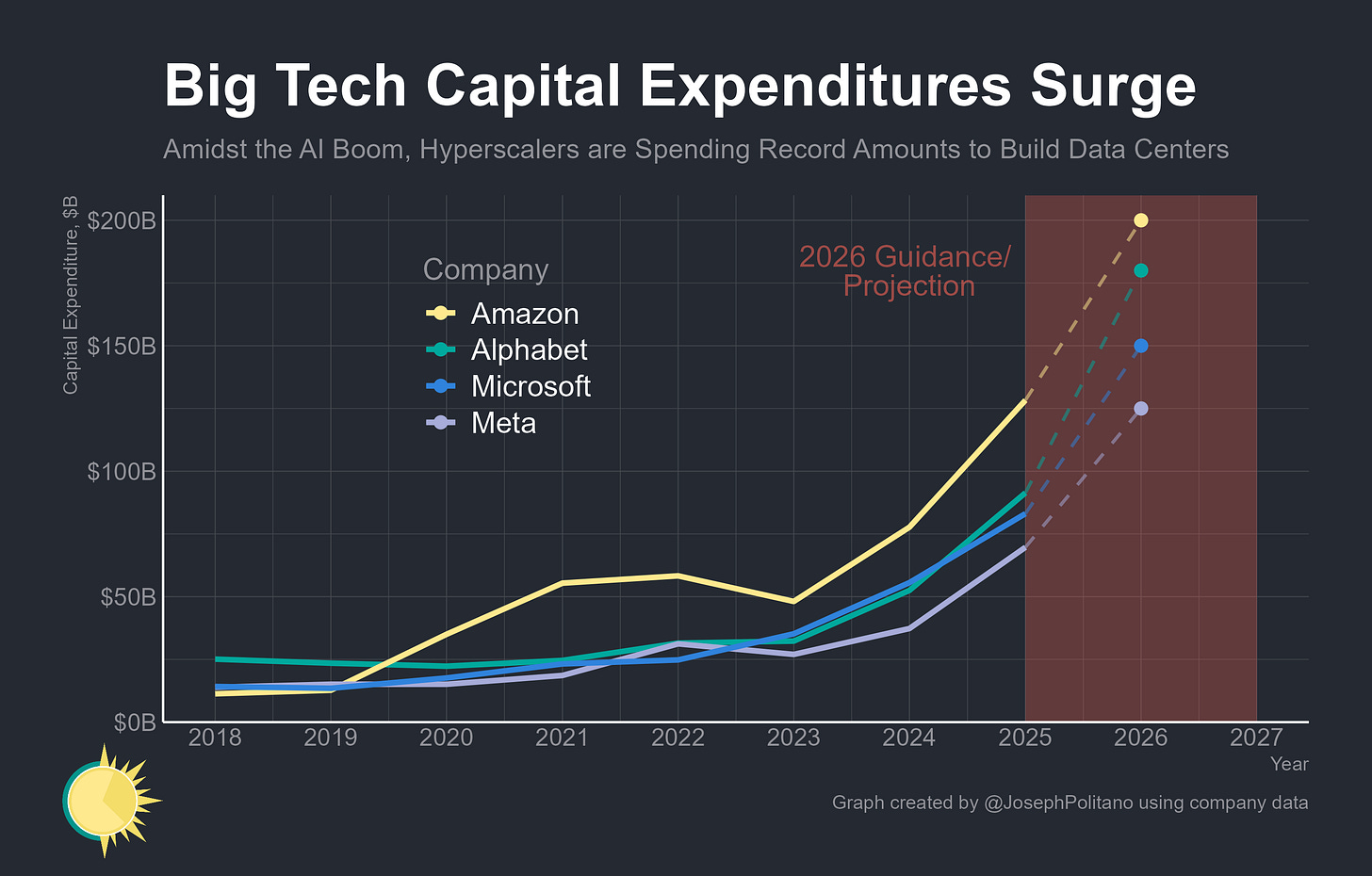

That investment is also poised to break more records throughout 2026—physical capital expenditures among the hyperscalers of Meta, Alphabet, Amazon, and Microsoft alone will comfortably exceed $600B this year, up from $370B last year. Alphabet alone expects its spending to reach $175B-$185B in 2026, with Meta spending more than $115B and Amazon a mammoth $200B. Yet this investment boom is an almost uniquely American phenomenon—computer investment in Canada and the UK are still below their 2022 highs, while EU and Japanese investment show no rapid acceleration. Even Chinese software and information technology fixed investment, the closest competitor to the United States, is up “only” 20% over the last year, and from a much lower baseline level.

In other words, America is making a globally and historically unprecedented bet on the success of Artificial Intelligence. As a share of the economy, that AI boom is already one of the largest investments in American history—dwarfing the peak of the broadband, electricity, or interstate highway buildouts and vastly exceeding the Manhattan or Apollo projects. And yet, US tech companies are doubling down, raising the stakes on their $1T gamble that AI models will continue their exponential capabilities growth and eventually become valuable enough to repay such a colossal investment.

Breaking Down the AI Boom

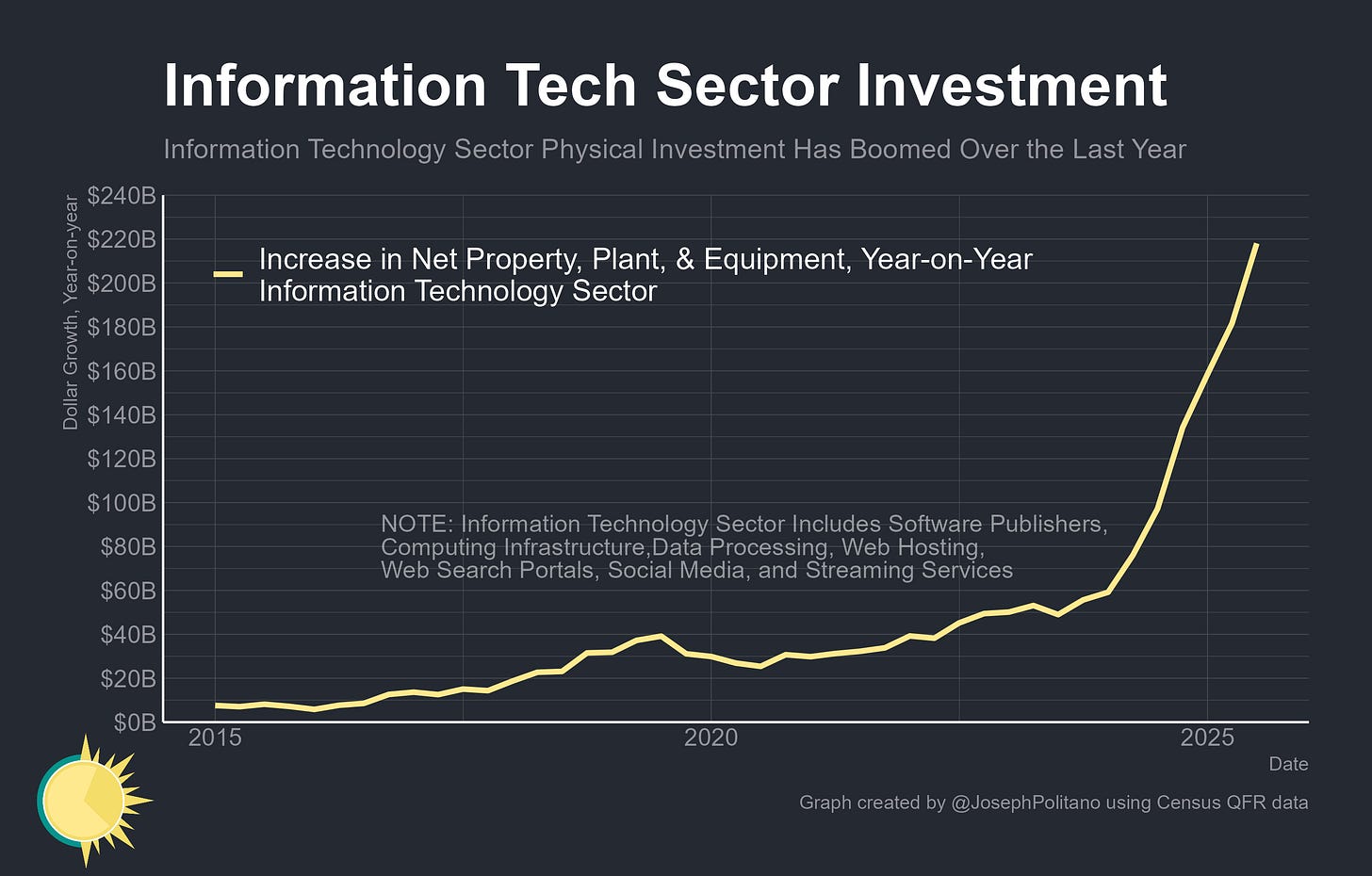

Since late 2022, US tech companies have shifted from a rapid-hiring asset-light growth model to a no-hiring, capital-intense one. Over the last year, these tech companies have cut roughly 20k jobs while their net holdings of property, plants, and equipment have risen by more than $215B, the fastest growth on record. In total, these companies now actively hold nearly $700B in physical assets, more than double their pre-ChatGPT levels. Given the rapid depreciation of electronics hardware, these numbers represent significantly more gross investment than the net values suggest.

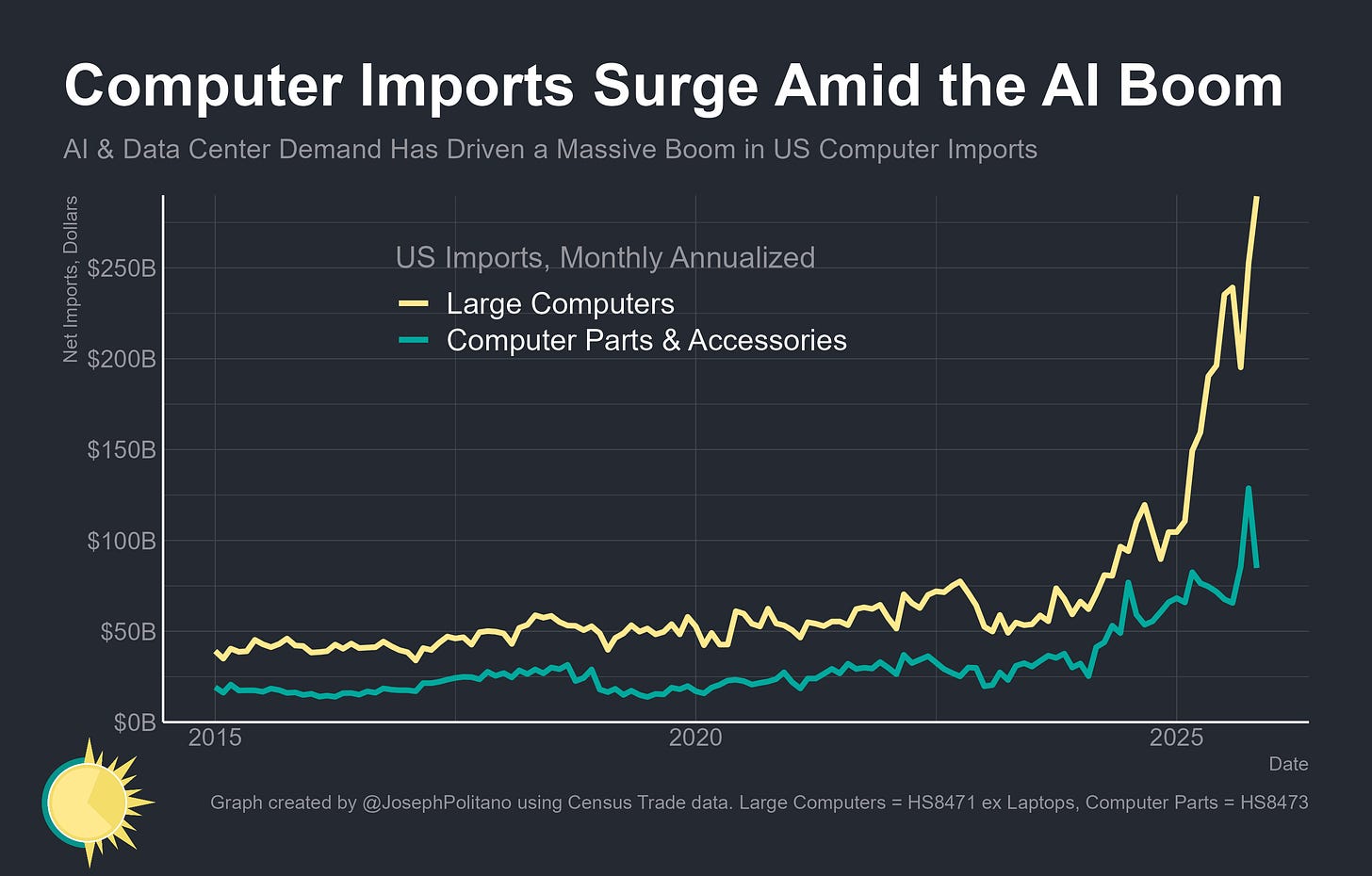

Yet the vast majority of this investment comes in the form of data center computers made outside the United States and thus have to be imported from countries like Taiwan, Mexico, and Malaysia. Real imports of these computers, plus the related parts and peripherals, have skyrocketed to a record high of nearly $400B annualized in recent quarters. Imports of large computers, including those that populate AI data centers, are up more than 220% over the last year and 300% since the launch of ChatGPT.

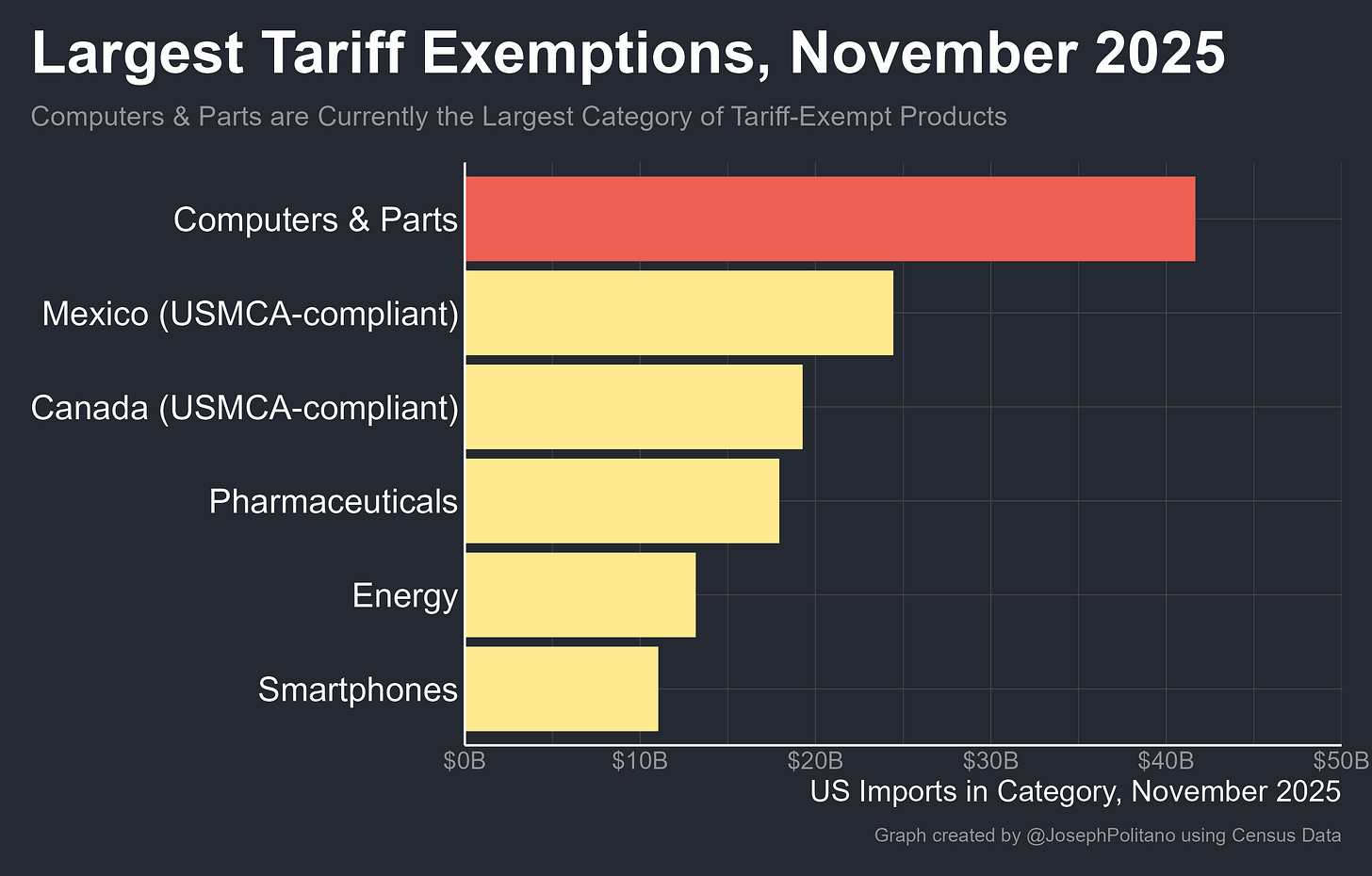

Those AI-related imports remain by far the largest exemption to Trump’s trade war. In November, the most recent month for which we have official trade data, nearly $42B in computer & parts imports were brought into the US completely tariff-free. The computer & parts exemption alone represented more than 16% of total US goods imports that month, roughly equivalent to America’s total imports from the entire Eurozone.

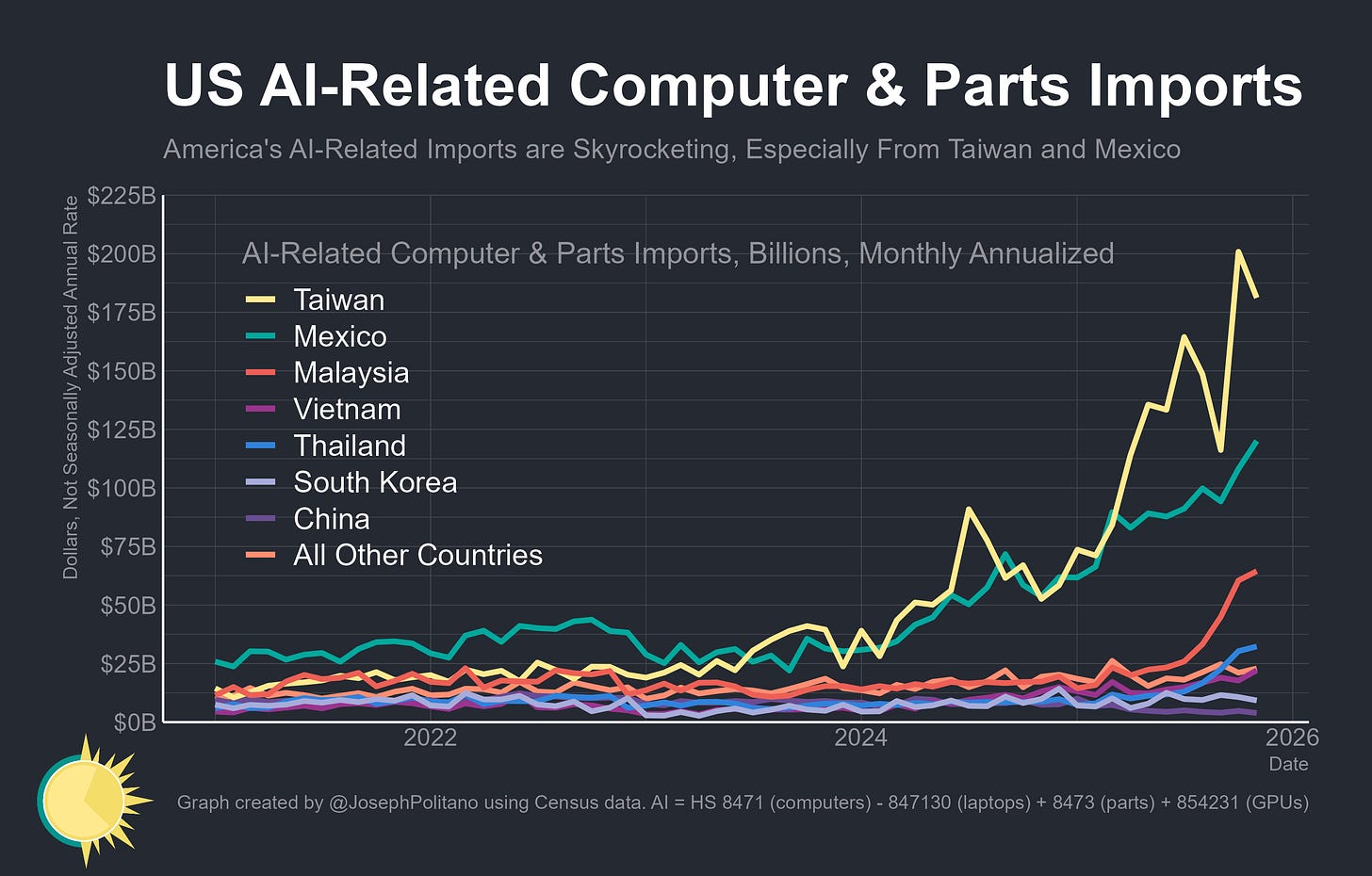

The vast majority of those AI-related computer and parts imports come from three countries—Taiwan, home of TSMC, Mexico, a leading center for computer assembly, and Malaysia, a significant chip & computer parts supplier. Imports from Taiwan in particular have skyrocketed, rising 670% over the last three years alone. In fact, the US now imports roughly as much directly from Taiwan ($20.3B in November) as from China ($21B). Likewise, AI-related imports from Mexico are up more than 200%, and desktops have now displaced passenger vehicles & pickup trucks as America’s largest import from its southern neighbor. However, those Mexican computers are also mostly made with Taiwanese chips, as Mexico’s imports from the island nation peaked at an $80B/year pace in October, up 315% over the last year.

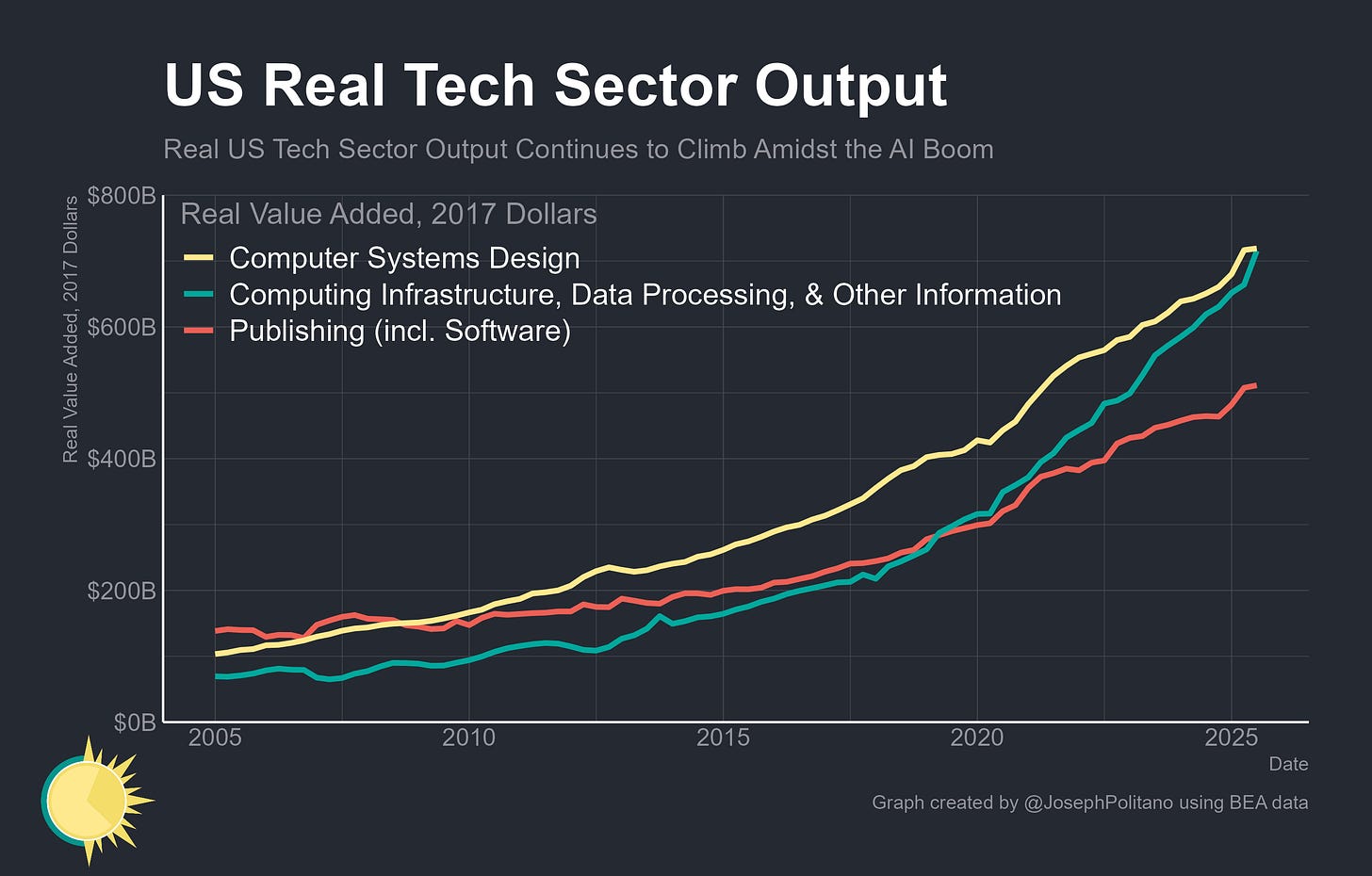

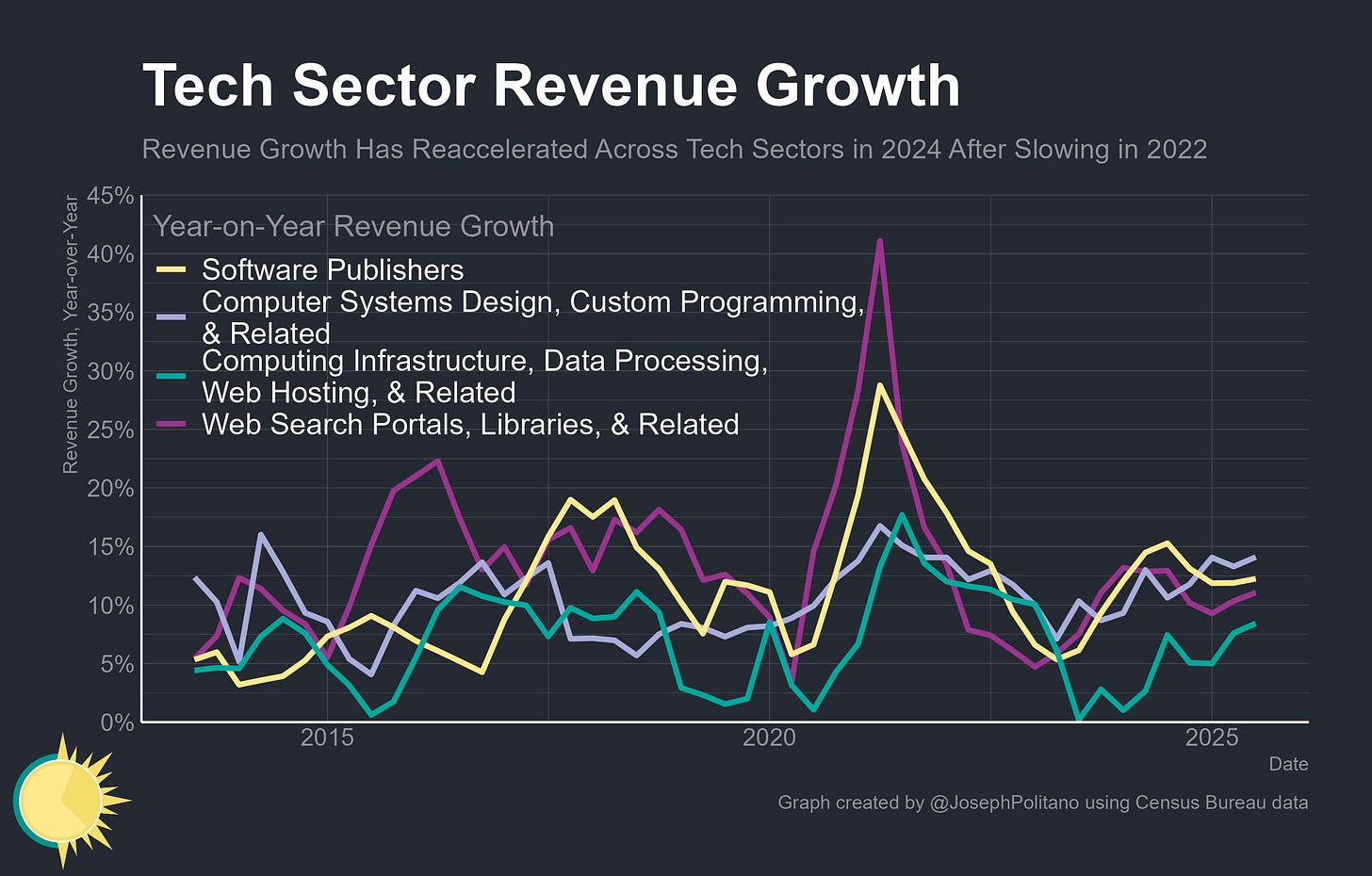

Meanwhile, real economic output has hit new record highs for each of the three main subindustries representing the tech sector—software publishing, computing infrastructure, and computer systems design services. Computing infrastructure output, which most directly represents the data centers backing AI training & inference, has risen by more than 15% over the last year and contributed 0.57% to the 4.4% annualized pace of growth in the 3rd quarter alone.

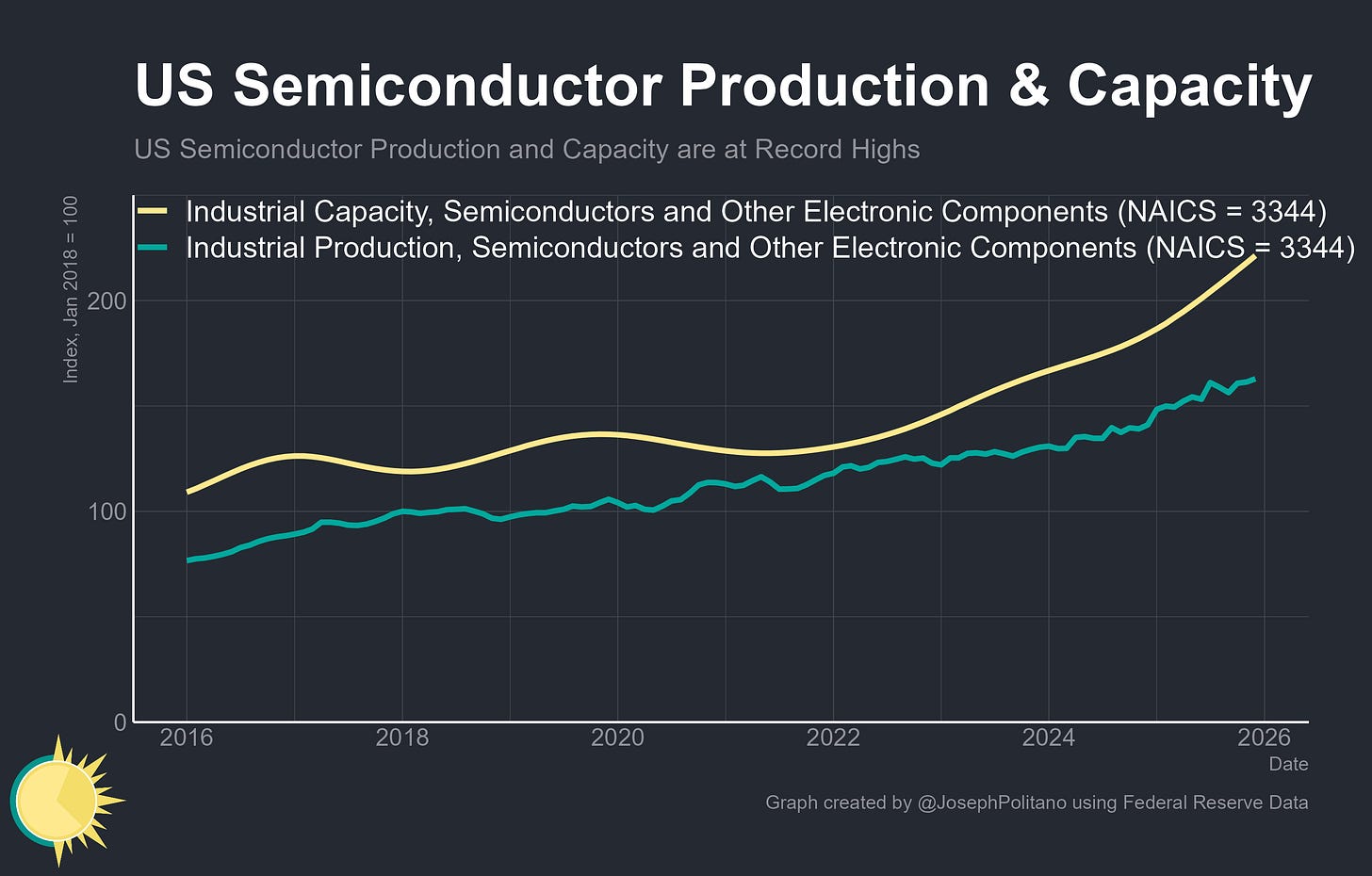

The AI boom, plus the completion of many semiconductor fabricators subsidized by the CHIPS Act, has helped push US semiconductor industrial production to record highs, up more than 15% over the last year and 30% since the launch of ChatGPT. American fabricator capacity has grown even faster, up more than 20% and 55% respectively over those same time frames. As more chip fabs come online, US production should increase further in 2026—even though US factory construction is declining, electrical & electronics factories are still being built at a rate of $95B per year.

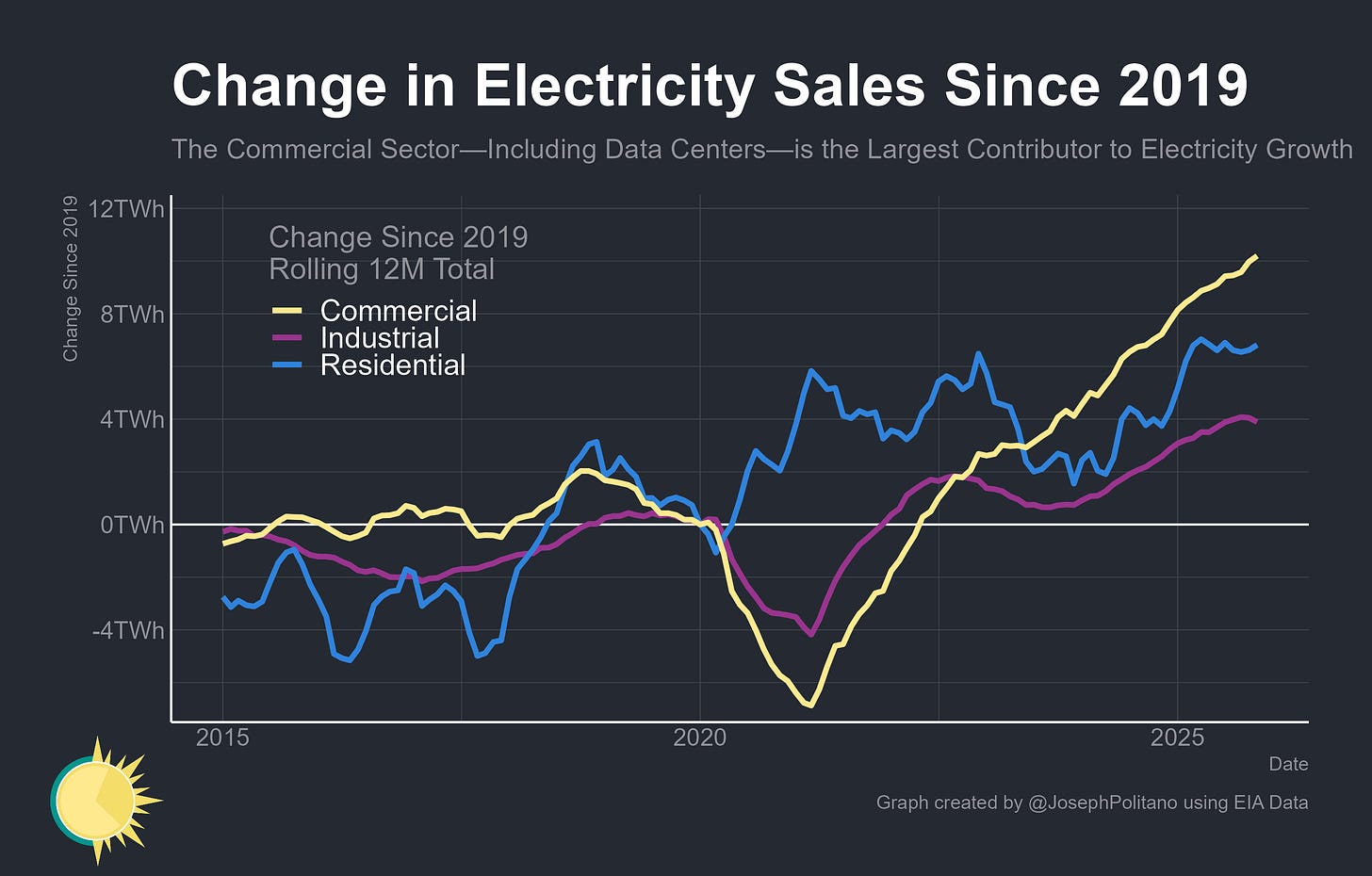

These data centers and chip fabs all consume electricity at extremely large scales, meaning electricity sales to the commercial sector—which includes data centers—have risen by more than 10TWh since 2019, significantly exceeding growth in both residential and industrial uses. That growth is not expected to slow anytime soon, as the US Energy Information Administration projects commercial power consumption will rise another 2.6% this year and 4.3% in 2027. It is also hyperconcentrated in the electricity grids of Texas’s ERCOT and the mid-Atlantic’s PJM, America’s two primary epicenters of data center construction. Data center demand is thus also contributing to the growing real investment in US electricity generation, which is hovering near a record high of $110B annualized, and growing commercial electricity prices, which are up nearly 7% over the last year.

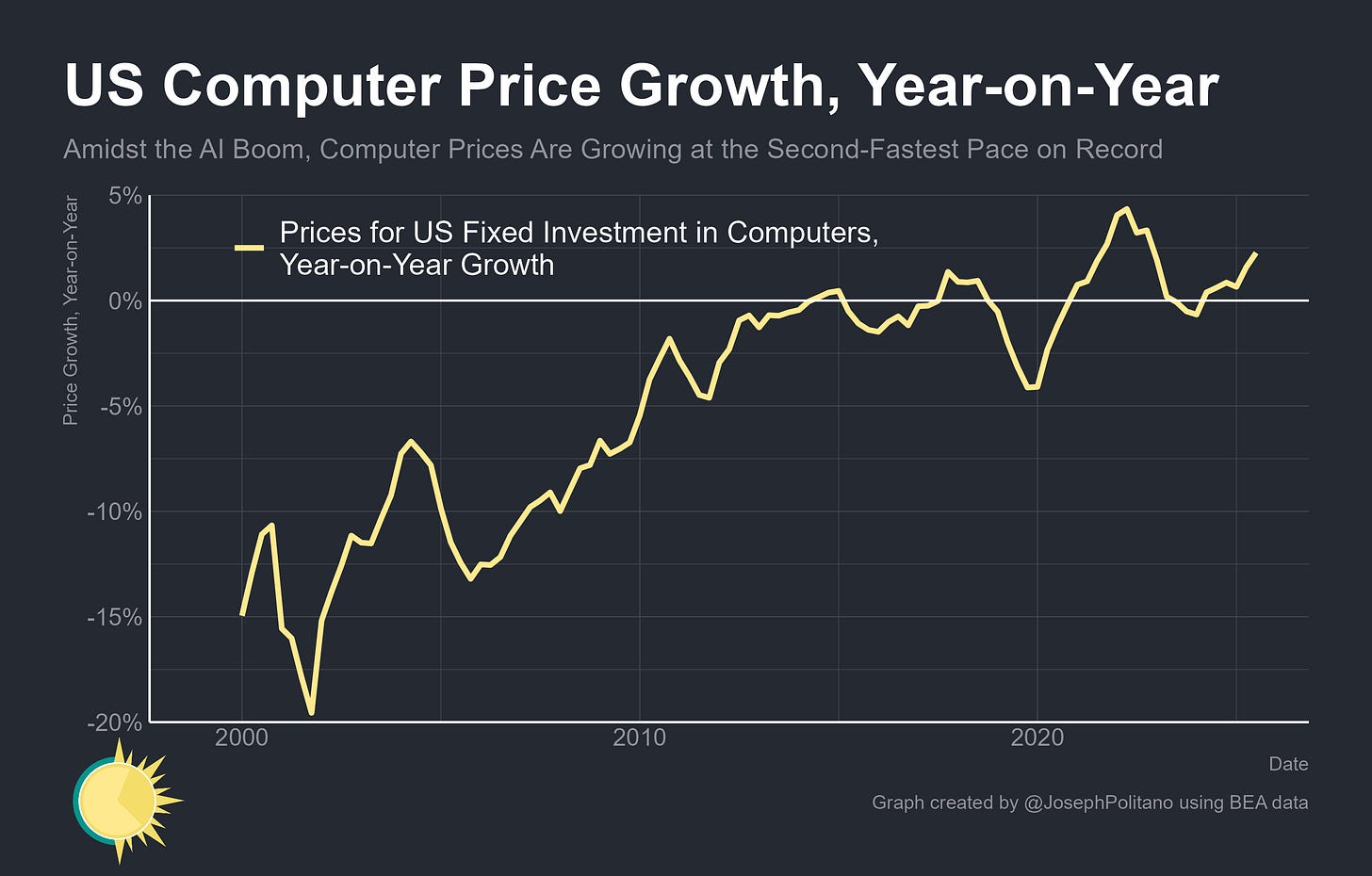

In fact, US spending on AI is so ravenous that it is breaking one of the iron laws of computing—throughout history, electronics almost always get cheaper over time as manufacturing processes improve and more power is squeezed onto smaller and smaller chips. Yet prices are now rising at the second-fastest pace on record, only trailing the worst of the COVID-era semiconductor shortages. That was a period of much more generalized price spikes as well, meaning that computer prices are actually increasing faster relative to aggregate inflation today than during the worst of the chip shortage. Some subcomponents have absolutely skyrocketed in price, with computer memory prices more than tripling over the last year—America’s AI boom is so massive that it is currently straining the capacity of global electronics manufacturers.

Conclusions

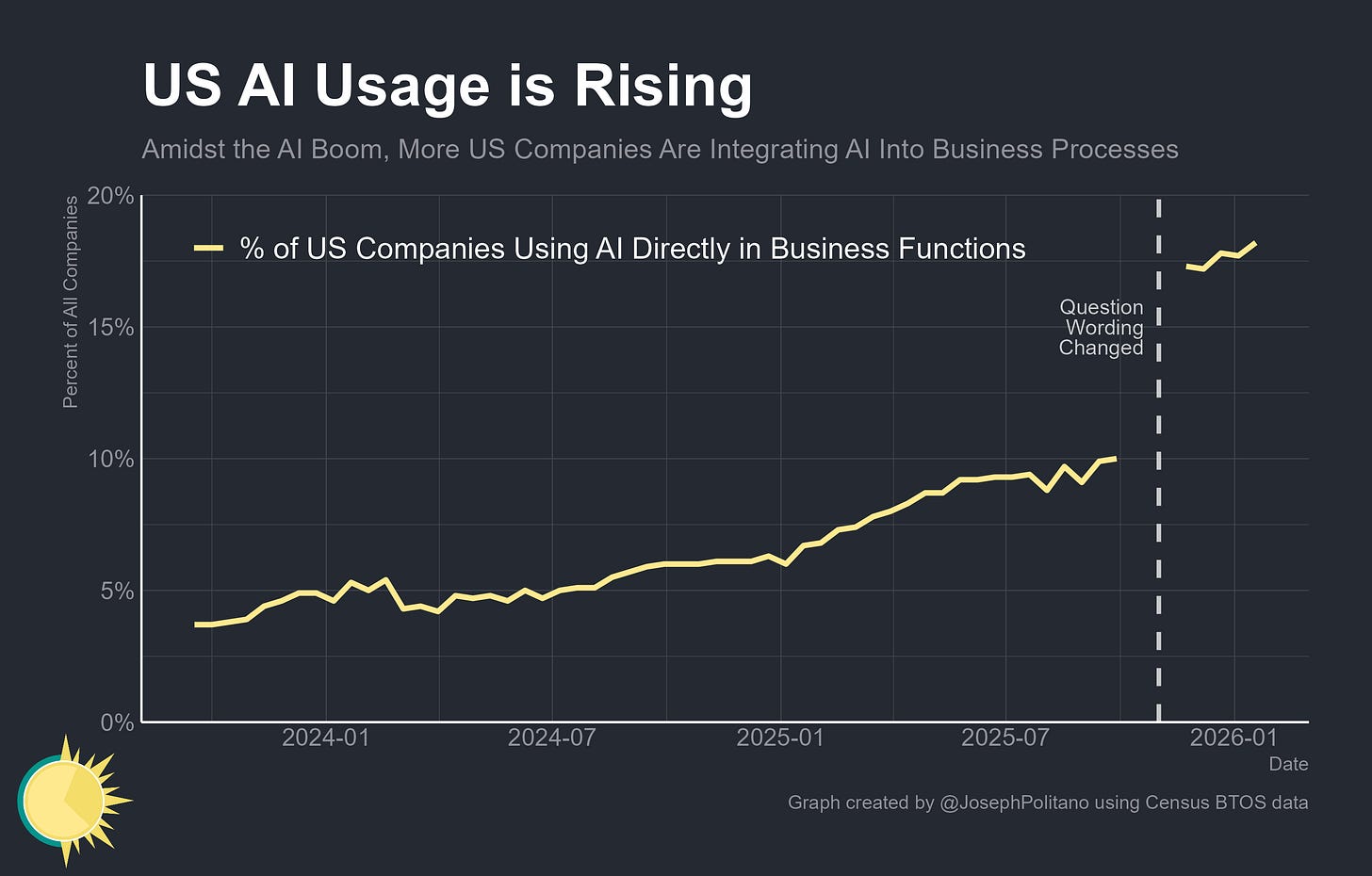

The share of companies using AI directly in their production processes has been continually rising over the last few years, with roughly 18% of firms now saying they use AI directly in their business functions. Among America’s largest firms and in some sectors like Information or Professional Services, that number can reach as high as 30%, and that’s before even accounting for the extremely common indirect use of AI among individual employees.

Yet despite rising AI usage across the board, most tech companies are not seeing a massive reacceleration of their gross revenue. Make no mistake, tech companies’ earnings have rebounded from their 2022-2023 lows and are now back in healthy territory; they are just vastly outmatched by the unprecedented growth in AI investment. OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and Meta all hope for this trend to be reversed in the coming years, for revenues to eventually catch up with the rapid growth in spending as is necessary for their investment gambles to pay off.

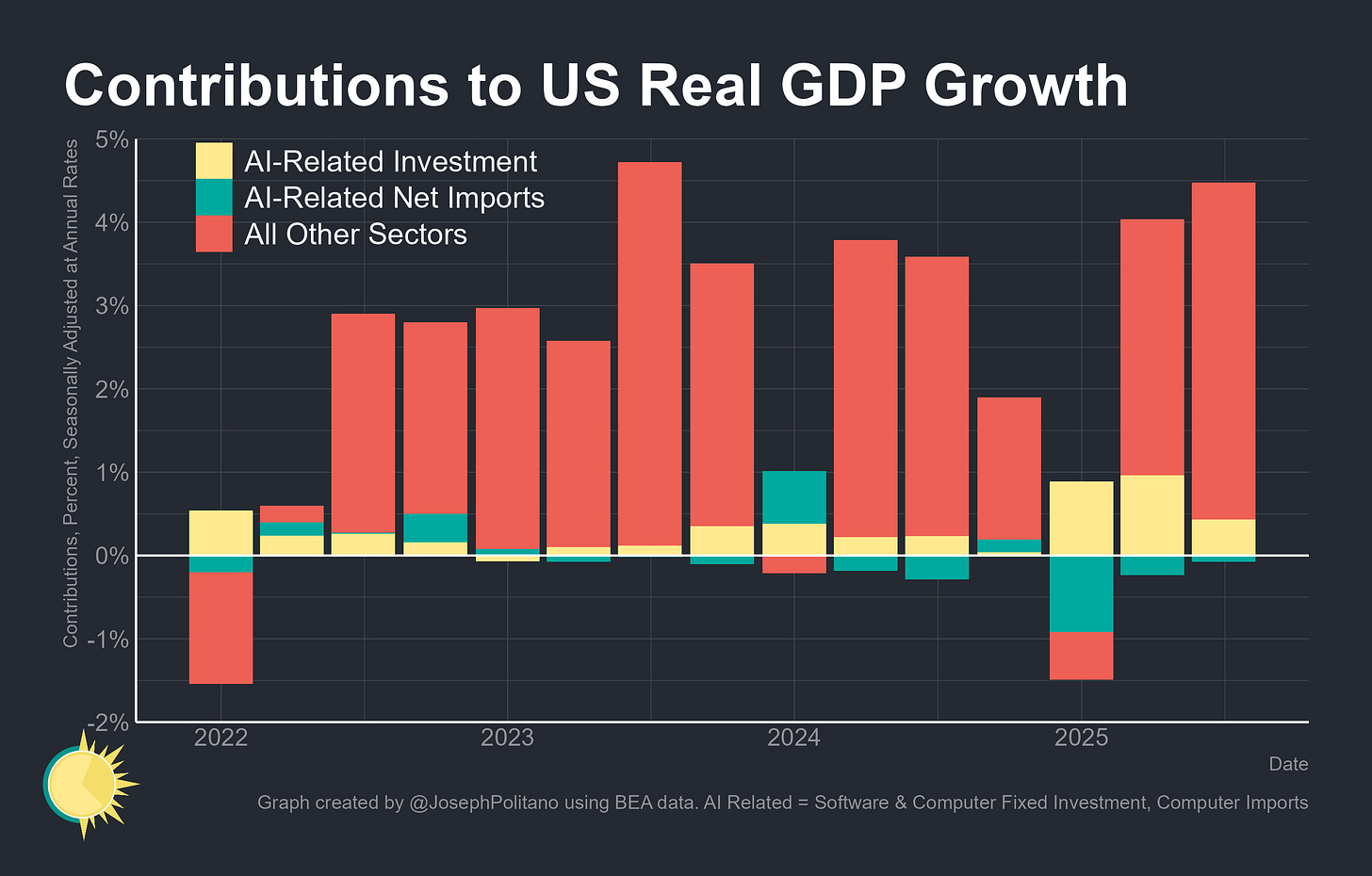

Yet in the meantime, the impact of this investment has been less pronounced from a national accounting point of view than the eye-popping headline figures would suggest. The tech industry has been a notable driver of GDP growth over the last year, but since the vast majority of computer fixed investment comes directly from imports, much of the short-term GDP boost from AI investment accrues to foreign electronics manufacturers (Taiwanese GDP is up 12.4% since late 2024). In the most recent data, AI investment net of imports only contributed 0.3% to the 4.4% annualized pace of US GDP growth.

In other words, the US economy is buoyed by the AI boom but is nowhere near entirely driven by it—meaning these investments have to pay off both as useful productivity tools for end users and a positive use of expensive compute for infrastructure providers if they hope to accelerate American growth. Even if the technology succeeds, losing companies—whether they be Microsoft, Google, or Anthropic—could be burned if their customers end up moving en masse to superior models developed by their competitors.

Still, recently released LLMs can now semi-reliably complete software development tasks that would take a human 6 hours, and capabilities measured in task-length have been doubling roughly every 7 months. Meanwhile, most AI companies still have massive spending capabilities from their other profitable digital ventures, and they’re easily able to tap investors for additional money at extremely high valuations. For now, America’s AI boom shows no signs of slowing down.

Very well done. I was a very active entrepreneur during the dotcom bubble, and this is so different. I remember the crazy valuations justified by eyeballs, and the many years it took to absorb all the dark fiber from over-investment. This time, we have real companies, generating real revenues, and every chip and all power deployed as soon as it comes online, not dark fiber phenomenon this time. We may need to see ROIs that justify the level of investment, but we clearly see this as real economics and not some speculative bubble justified by crazy ideas about the future that are not based in reality. I also find the rate of change so much faster than in the dotcom era. I did some measurements of this recently, comparing adoption rates, and found that we are moving 50% faster with AI than we did with the internet. It is hard, maybe impossible, to keep up with all that is changing on a daily basis.

And all we'll have to show for it is the ability to generate meeting notes and AI p*rn.