California Keeps Losing Tech Jobs

Amidst the AI Boom, Employment in Silicon Valley is Shrinking

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing, you’ll join over 72,000 people who read Apricitas!

America’s tech industry is in the midst of a historic boom driven by the race for artificial intelligence. Hyperscalers are spending hundreds of billions of dollars to build data centers, AI investment is driving record shares of overall GDP growth, and AI systems themselves are being increasingly deployed throughout the economy. Real economic output in the three major AI-related subindustries—software publishers, data infrastructure providers, and computer systems designers—have all skyrocketed over the last few years.

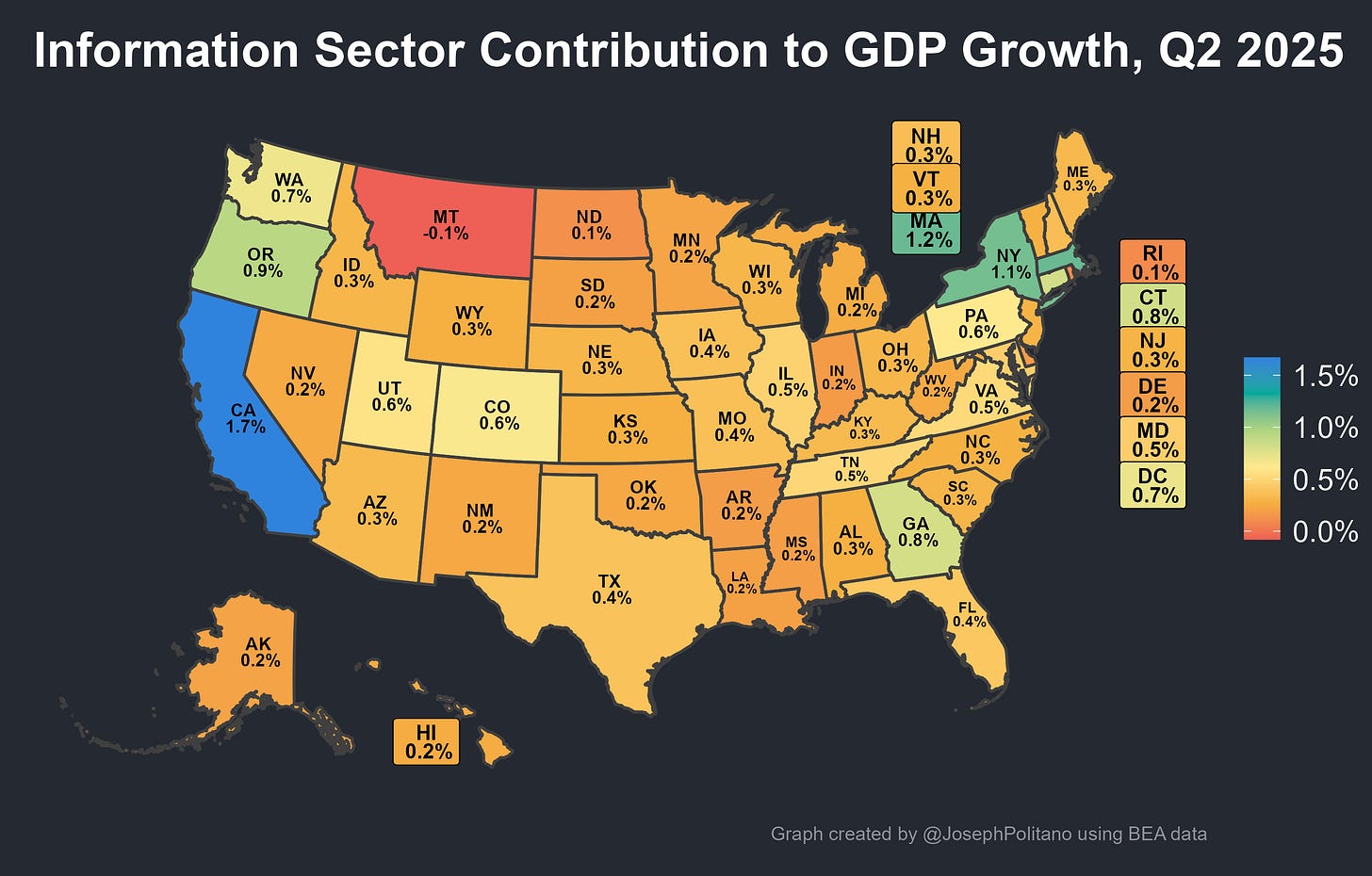

The companies behind this tech boom are heavily concentrated in California—the seven largest companies in the world are all AI-related, and five of them (NVIDIA, Apple, Alphabet, Meta, & Broadcom) are headquartered in the Bay Area, while the remaining two (Microsoft & Amazon) are Seattle companies with major operations in San Francisco. The information industry, which covers most tech companies, contributed a full 1.7 percentage points to the 4.3% annualized GDP growth California saw last quarter.

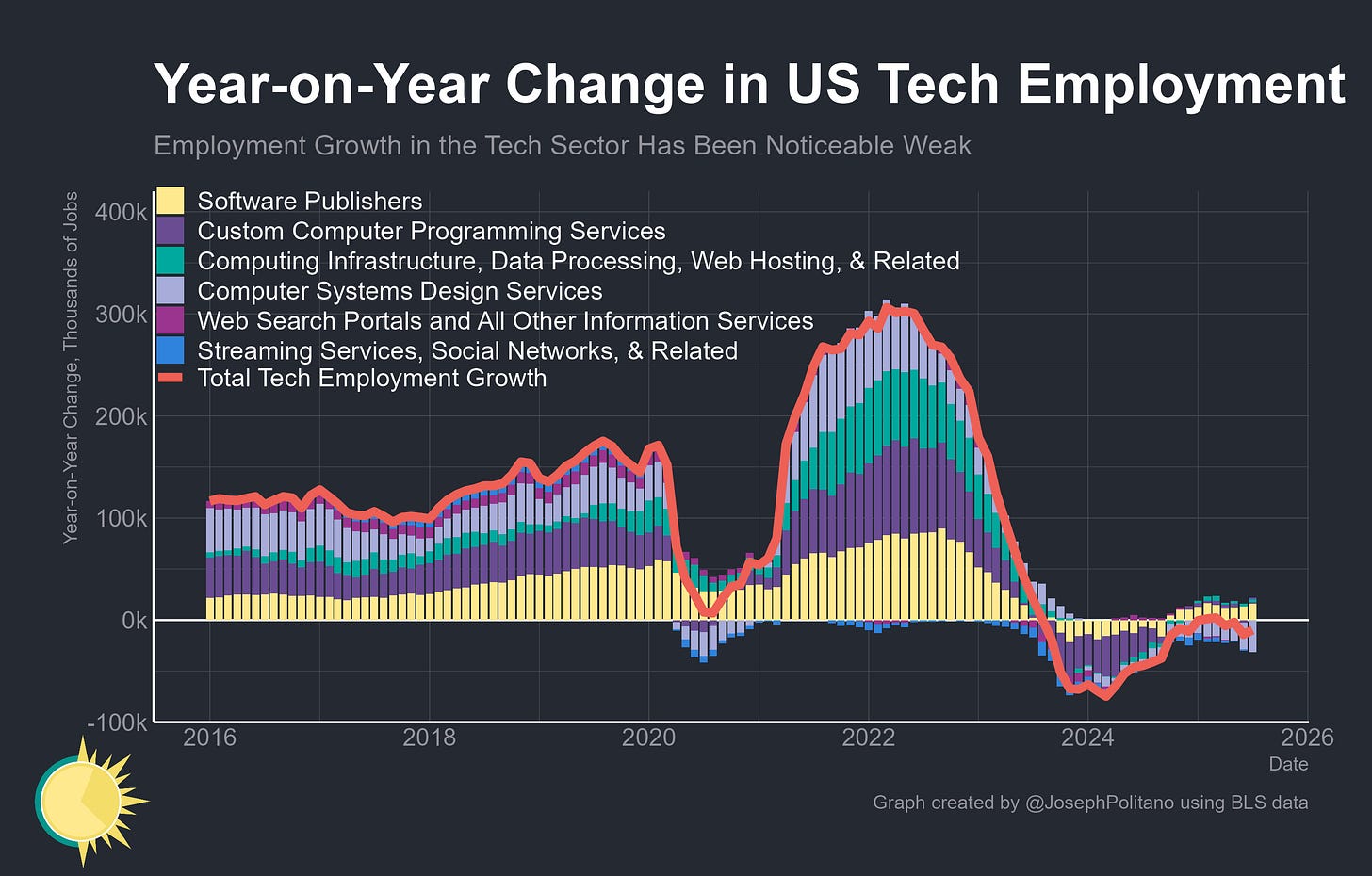

Yet amidst the AI boom, the US continues bleeding tech jobs—tech employment is down 90k from its 2023 peak and has declined by more than 10k over the last year. That is a massive slowdown from the 300k-per-year job growth pace seen in the 2022 tech boom or the 150k-per-year pace regularly sustained in the years before COVID. Unemployment rates for computer and math-related occupations have risen roughly 1% since summer 2023.

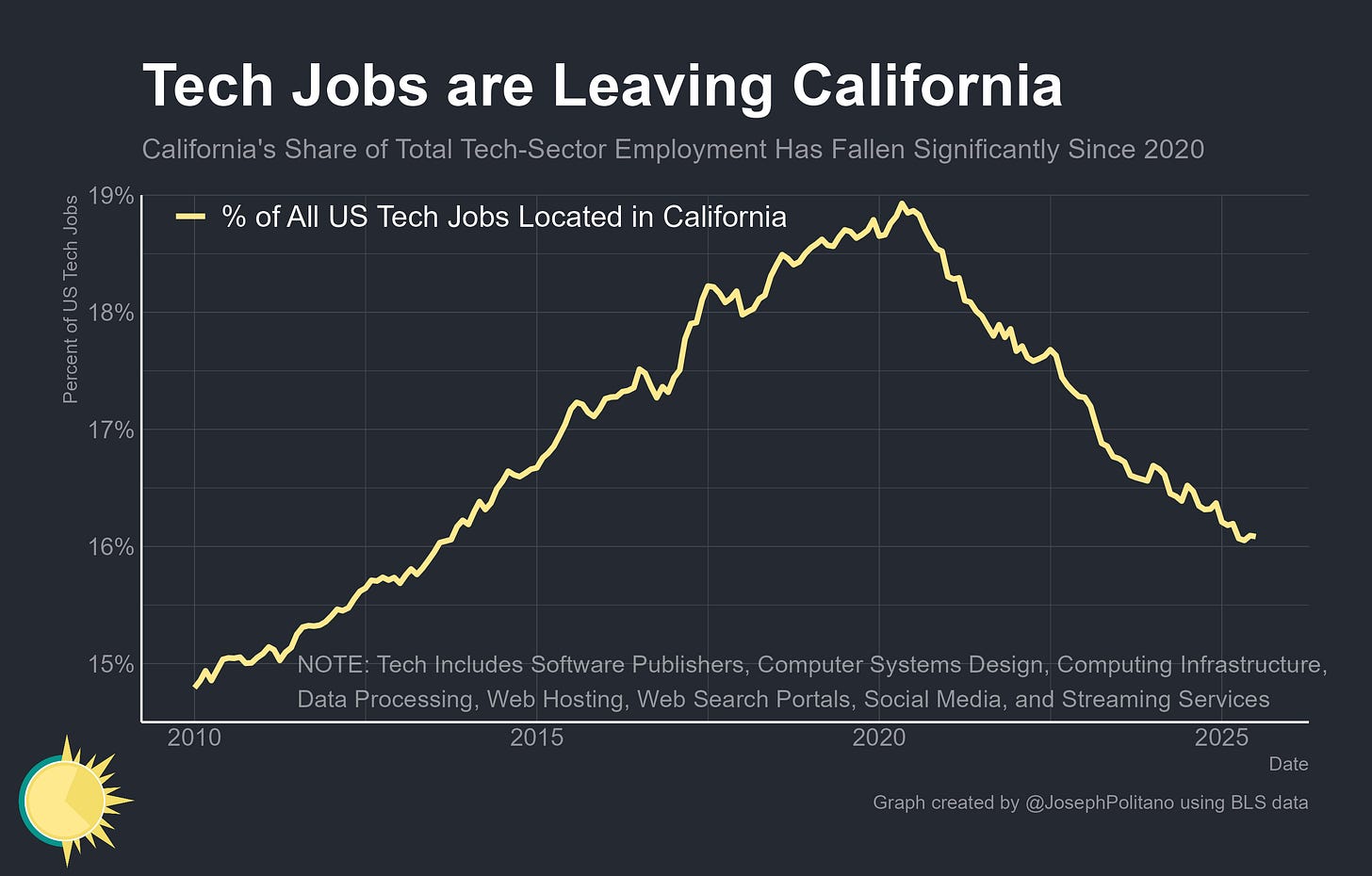

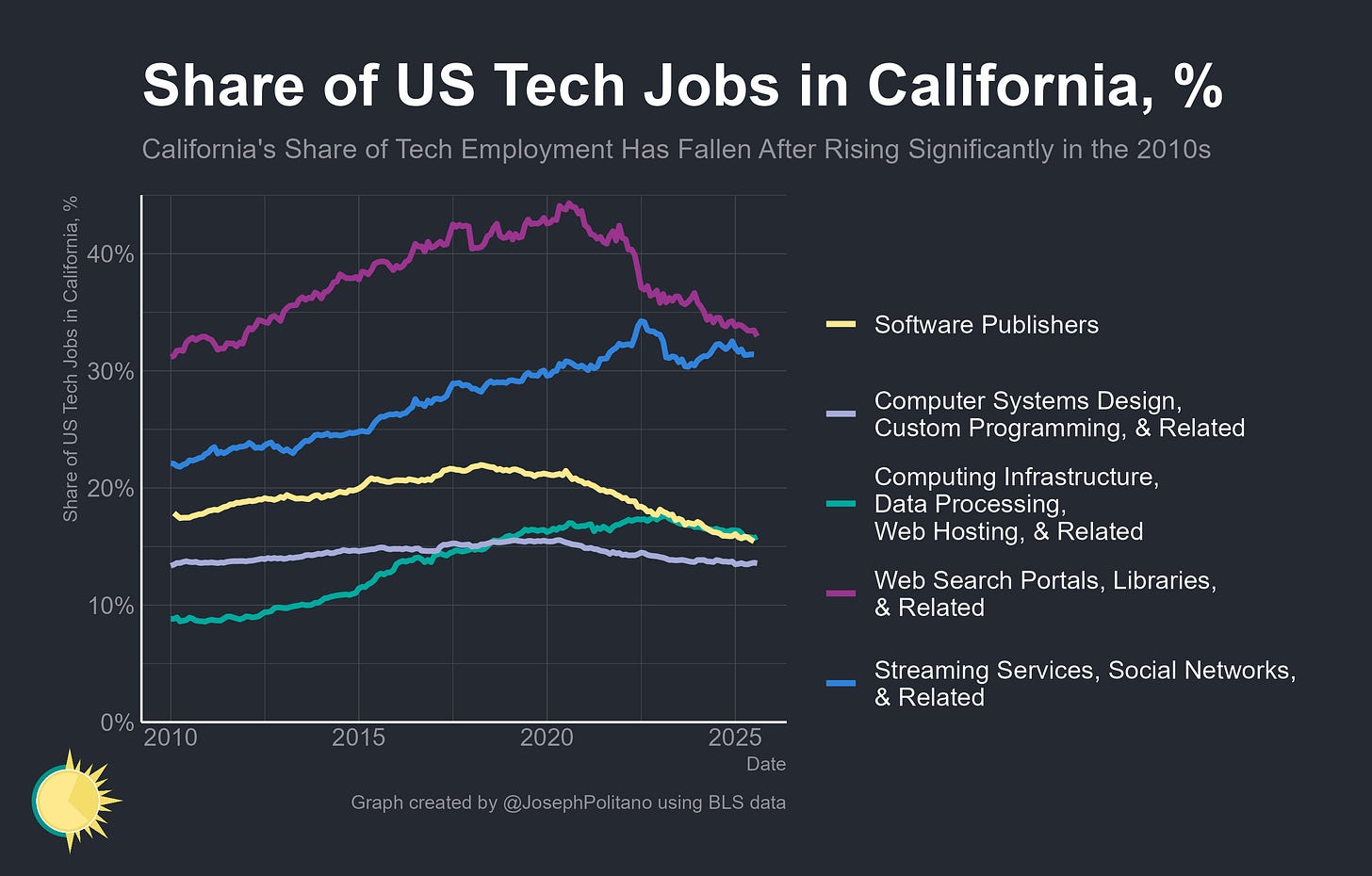

Plus, the tech job slowdown is hitting the California job market doubly hard, as the state is a shrinking share of US tech employment even while national tech employment is declining. Before COVID, nearly 19% of all US tech jobs were located in the Golden State; today that share is down to nearly 16%. Over the last year alone, California's share of tech employment has declined by another 0.4%.

It’s hard to quantify the precise effect of the AI boom on overall tech industry employment—new employees are required for the design and development of AI models, but these models often go on to displace coding jobs in other tech companies. The massive downturn in tech employment preceded the deployment of ChatGPT and has decelerated, not accelerated, since 2022.

Yet at this point, it is increasingly hard to deny some negative impact of AI on software and computer science jobs. This is now the largest and longest sustained drawdown in tech employment since the dot-com bust, significantly worse than either COVID-19 or the 2008 recession. Despite tech stocks rebounding, interest rates falling, and fixed investment surging, nothing has caused job growth to return to anywhere near normal levels.

Meanwhile, California’s high cost of living and lack of infrastructure investment continue to drive tech jobs to other states. Prices for housing and energy remain some of the highest in the nation, yet the state builds too little of either, making it hard to accommodate newcomers in its growing economy. These problems affect tech acutely but are mirrored across all sectors—California’s aggregate job growth is still 0.5 percentage points slower than the rest of the nation’s. That means Silicon Valley remains in an investment-heavy, hiring-light posture, and California remains at the epicenter of the tech industry’s weak job market.

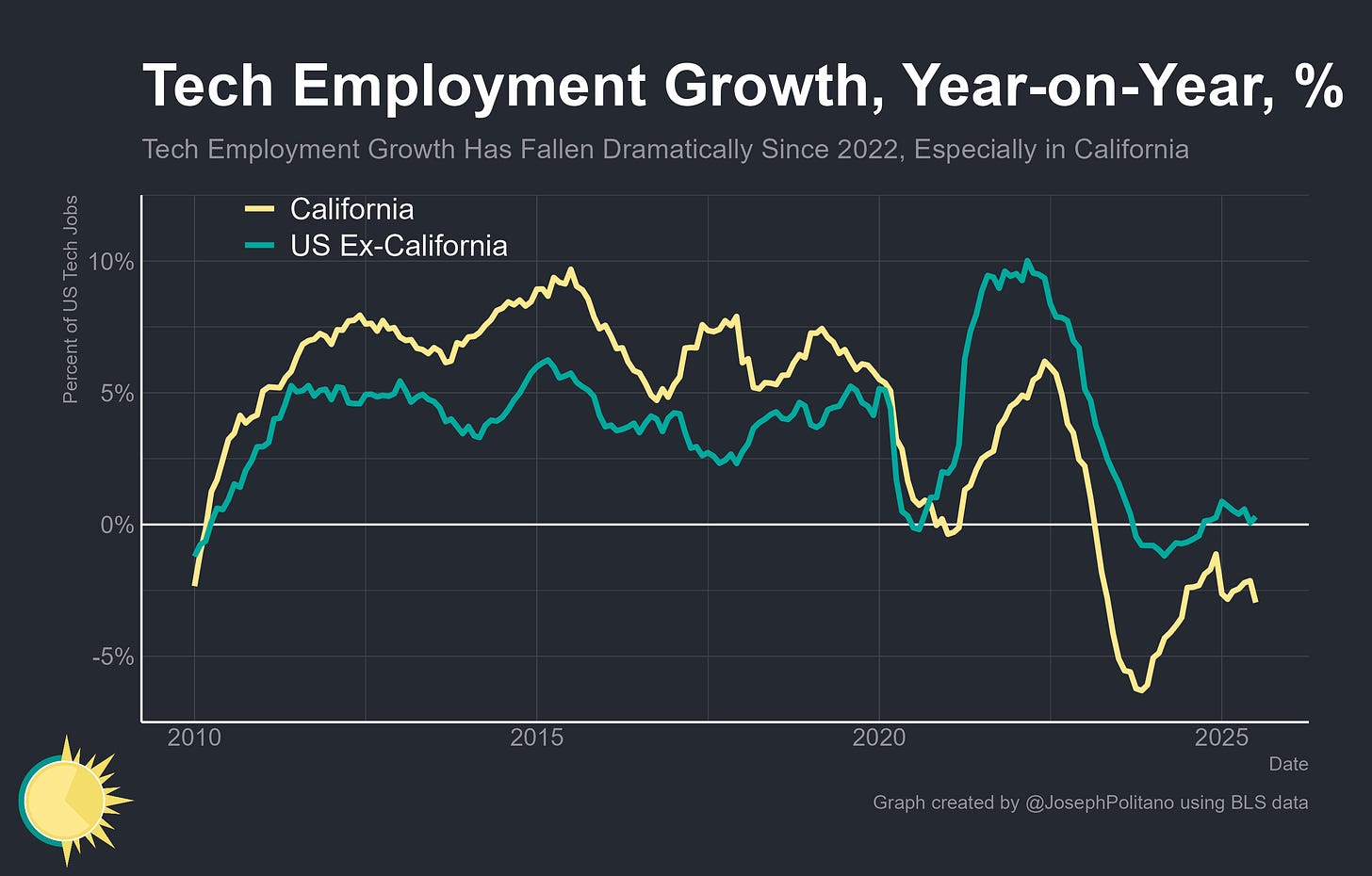

Silicon Valley Slump

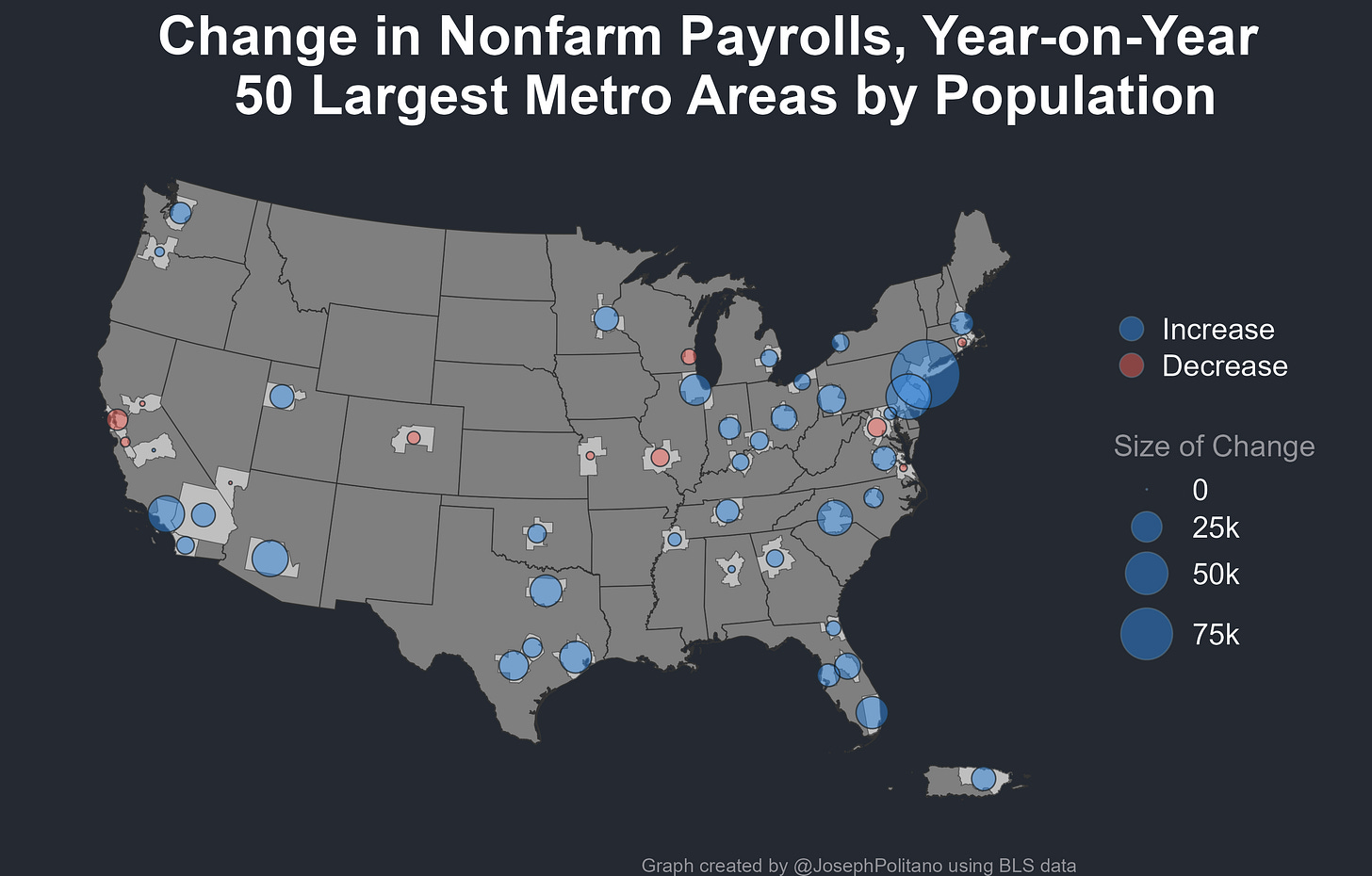

Tech job growth dynamics between California and the rest of the US saw a massive structural shift right after the pandemic hit. Both continue to follow a relatively similar cyclical boom-and-bust pattern; it’s just that California was perpetually growing 3-4% faster than the rest of the nation through 2019 and has been growing 3-4% slower since 2021. Where are these new tech jobs going instead? While we don’t have extremely detailed data for most states, what data we do have suggests the largest destinations for tech workers are Florida, Texas, and Washington.

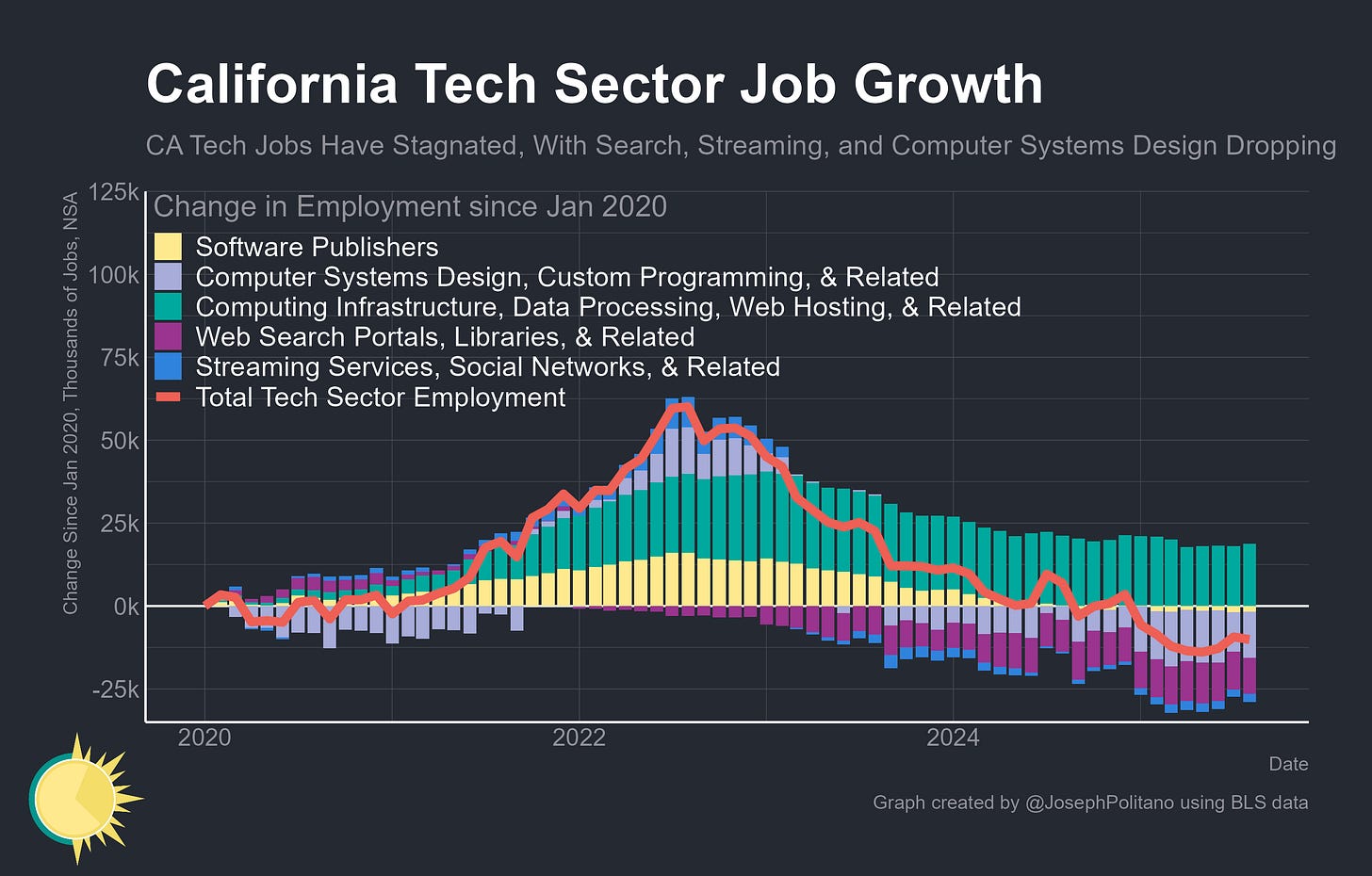

In total, California’s tech-sector employment grew by 60k between the beginning of 2020 and mid-2022 before declining by 71k in the three years since. Web search portals (like Google) and computer systems designers (like IBM) have led the decline, while computer infrastructure providers (like Amazon Web Services) have held up the strongest.

Those job losses mean that California’s share of US software publishing jobs has fallen to the lowest levels in the 35 years for which data is available. Meanwhile, its share of computer system design jobs has fallen to the lowest level since 2010, its share of web search jobs has fallen to the lowest level since 2011, and its share of computing infrastructure jobs has fallen to the lowest level since 2019.

The slowdown in the tech job market means that San Francisco has seen the largest job losses of any metro area in the US, with employment dropping by 11.6k over the last year (though it is certain to be overtaken by DC later this year as the full effects of DOGE show up in official data). San Francisco has also seen the largest employment drop of any major metro area since COVID, with its employment declining by 3.8% even as national employment has risen by nearly 5% and 84% of major metro areas have recovered to 2019 job levels. Nearby San Jose MSA has also suffered, though not quite as harshly, as their employment is down 1.4% since the beginning of 2020 and they’ve lost 2k jobs over the last year.

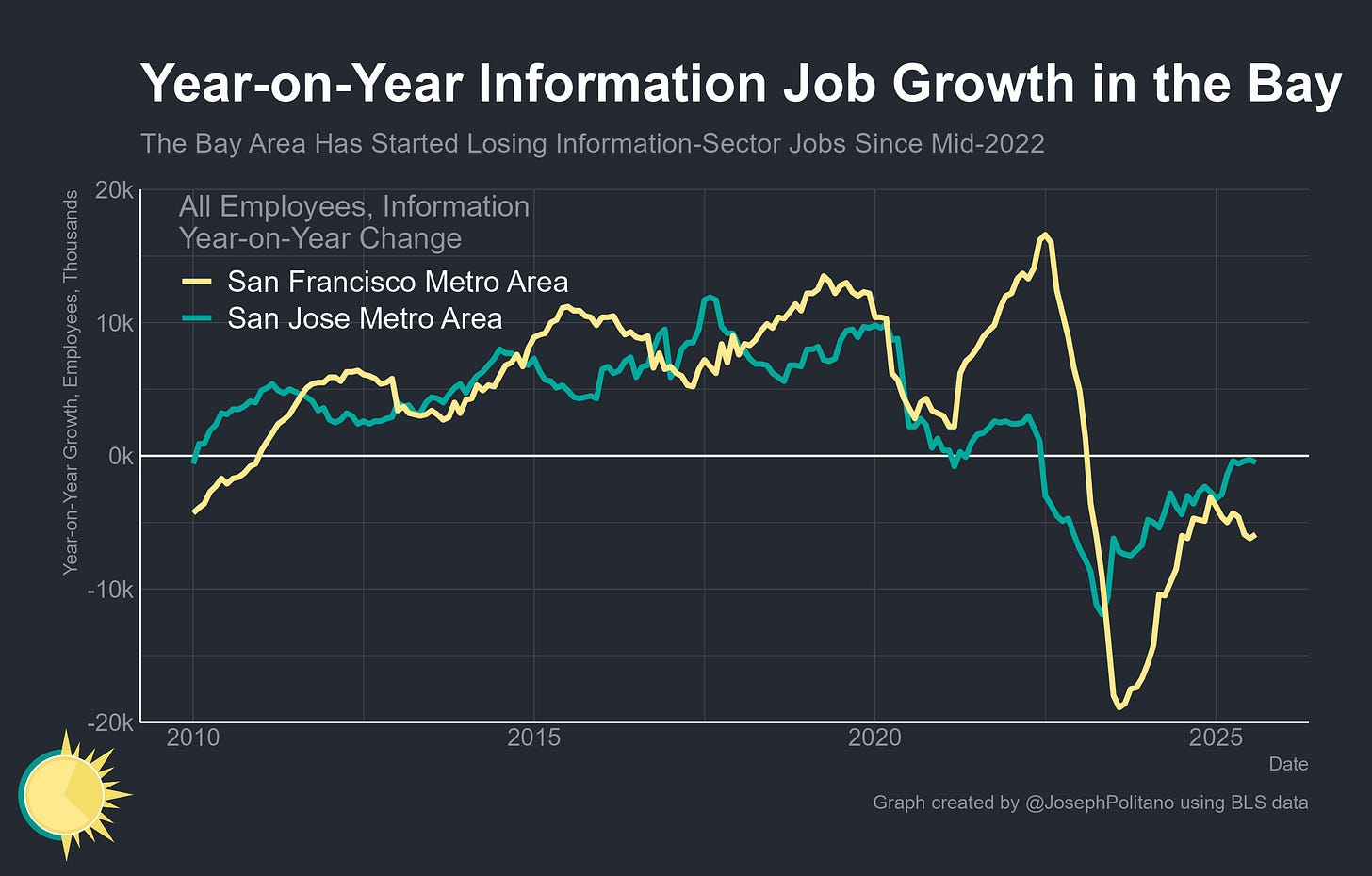

Looking narrowly at the information sector, both the San Francisco and San Jose metro areas have been steadily losing jobs since mid-2022. The pace of loss has eased up in both MSAs, and San Jose is doing much better overall than San Francisco, but at no point has the bleeding completely stopped.

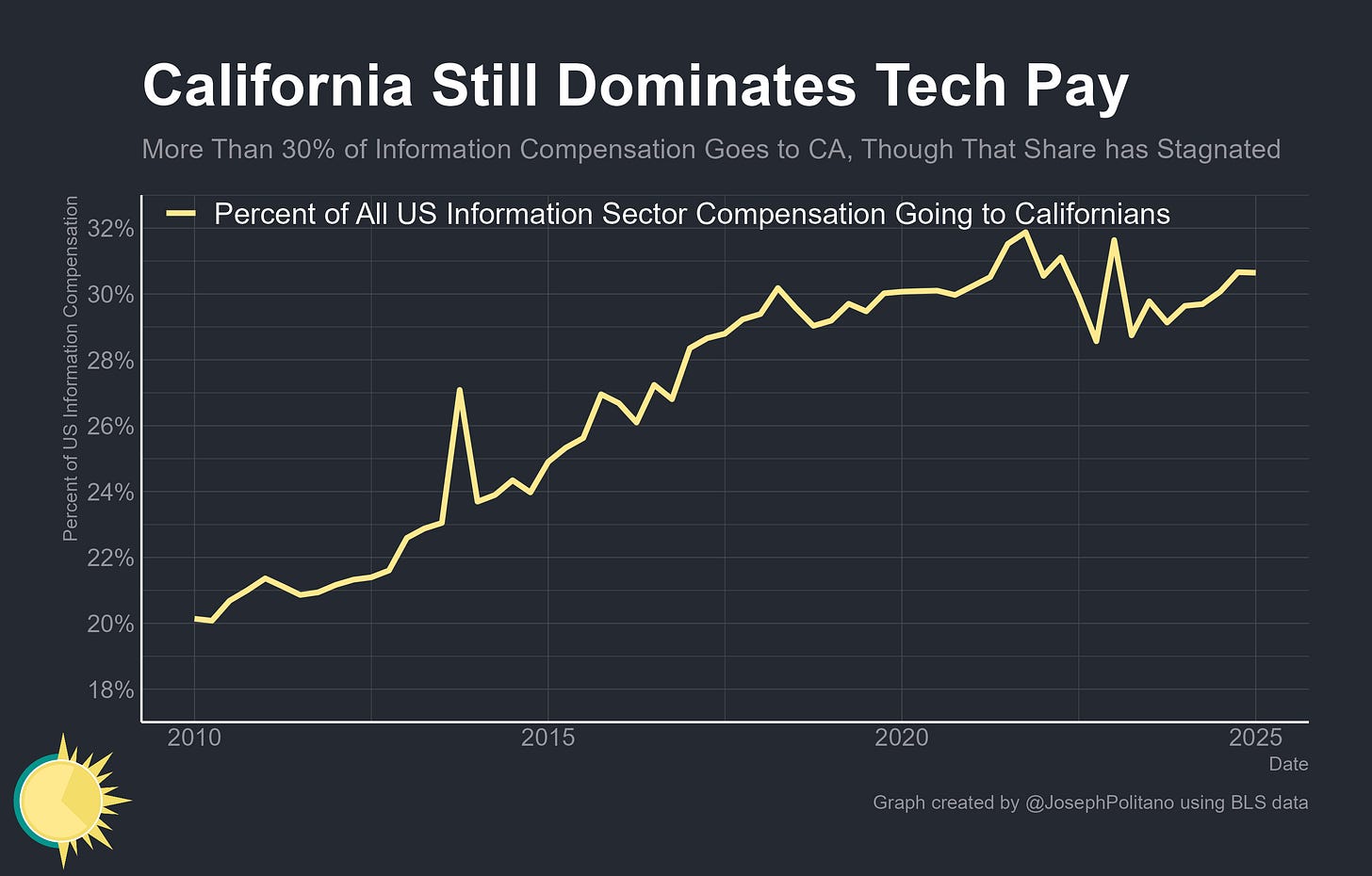

The good news for Californians is that while tech-sector jobs continue to leave the state, the jobs that remain are disproportionately high-paying. The share of information sector compensation going to Californians is actually up slightly from its pre-pandemic peak even as the share of information-sector employment has shrunk dramatically. Nearly one-third of all tech-related wages and benefits still go to residents of the Golden State.

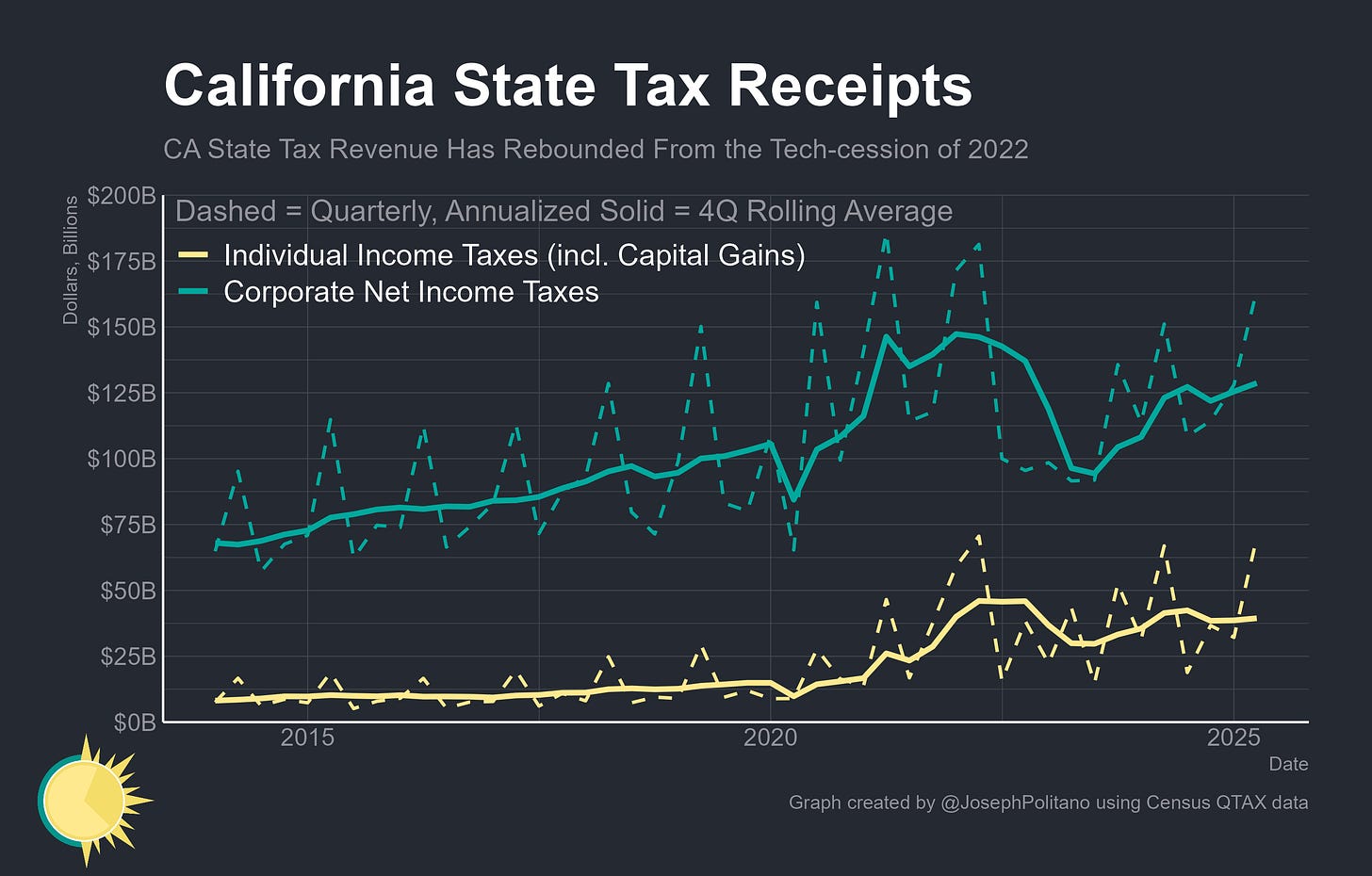

That’s been an important alleviating factor for California’s state government, which is extremely dependent on Silicon Valley to fund public services. The state’s income and corporate taxes are paid disproportionately by the high profit margins, large salary packages, and cyclical capital gains of the tech industry. The AI boom has allowed California tax receipts to rebound from their 2023 lows, though they still remain well below their 2022 peaks.

With the worst of the tech-cession over, the Golden State’s economy is once again growing faster than the national average, even though it is no longer comfortably blowing past the competition as it was pre-pandemic. Indeed, even amidst its current rebound California still trails both Texas and Florida in GDP growth over the last year, and the state’s economy is growing at a rate more than 25% slower than it did in the five years pre-pandemic. This is a partial recovery but not a true return to form.

Conclusions

Several factors will continue to push against California’s economy in the years to come. The state has the nation’s most immigrant-heavy economy, and tech is one of its most immigrant-heavy industries—the Trump administration’s drastically tightened restrictions on legal immigration are thus certain to weigh heavily on their economy. California’s high cost of energy also means that despite the tech industry’s concentration in the Bay Area, few data centers are planned in the state itself, pushing more of the AI ecosystem to places like Virginia, Oregon, and Texas.

Yet there are also important tailwinds for California. The state has just passed SB79, a bill that allows more housing construction near transit stops throughout the state, representing one of the largest upzonings in the modern United States. That will help significantly alleviate California’s chronic housing shortage that pushes so many workers and businesses out of state. Telework rates, previously a major driver of California outmigration, have also stabilized or declined in the last couple of years. These look likely to slow the rate of Silicon Valley job losses, but on their own they will not be enough to completely stop the steady relocation of tech jobs out of California.

The more pressing question is the more difficult one: what will happen to the tech job market as AI continues to be deployed throughout the economy? Will they be more like journalists, whose jobs were decimated by the internet age, or like radiologists, whose jobs have surprisingly thrived thanks to AI? So far, they’ve held up much better than artistic industries like graphic design services (where jobs are down 10% since late 2022), but are obviously still stuck in their worst job market in years. Only time will tell how much AI will replace or complement existing programming jobs as the technology continues to develop.

The devil is of course as always in the details. Because the nature and employment structure of what we call "the tech sector" changes so rapidly, it really does depend on how jobs are categorized. So I'd be slow to read too much into what are relatively small changes. Something we do know from other data is that companies are trying to use AI coding assistants to replace entry-level and lower level software engineering jobs. Also that the same is likely happening in tech support roles. However many, maybe most, of those jobs are located outside CA (not least because you couldn't live in the Bay Area on the salaries offered for those jobs). That may be part of why average pay in CA tech jobs is up.

A second point is that while Data Centres create quite a few jobs during their construction (up to the thousands), they result in very few jobs once in operation (often in the tens). Since they also cause a rise in electricity costs (and lower availability for domestic supply, hence housing expansion), they may not be a great loss to CA overall. There's no reason to expect any "spillovers" from then either, since their whole point is to be location free.

It's not clear that the loss of jobs in tech is due to structural changes, or a correction after the massive over-hiring between 2019-2022. Until we see the end of the shakeout of overhiring I don't think we'll really have a clear picture how employment in tech has changed.