Fight Inflation - With Housing

Or: How I stopped worrying about inflation and built more housing

Photo courtesy of Alex Muresianu (@ahardtospell)

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Component-level analysis of inflation – that is, disaggregating inflation indexes to identify how different sectors, goods, or services contributed to the inflation rate – is a critical tool in analyzing economic activity and identifying supply constraints that are hampering economic growth. Recent headlines have focused on vehicle prices, airfare prices, and energy prices as large contributors to the transitory inflation Americans are experiencing as we exit the pandemic. In recent decades, however, none of these categories have contributed nearly as much to inflation as housing. The price increases in the housing sector are of particular importance because of housing’s role as a basic need, its large presence in most American’s budgets, and the regressive nature of housing price increases. To stop increases in housing prices, we need to eliminate exclusive zoning regulations that prevent the construction necessary to alleviate the housing shortage.

First of all, a clear distinction needs to be made between the idea that housing contributes to inflation and the idea that housing causes inflation. If nominal housing prices were stable or decreasing over the last 20 years it does not mean that inflation would automatically be lower. Consumers would shift money that would have gone to housing to other goods and services and the Federal Reserve would alter monetary policy to ensure inflation remains at its 2% target over the long-run. The long-run aggregate price level is only a function of money supply, output, and money velocity. The value in component-level analysis of long-run inflation dynamics is not to say “if housing prices were stabilized, inflation would subside” but rather “the persistent rise in housing prices when compared to other prices shows that housing supply is extremely constrained and housing demand is extremely inelastic.”

It is also worth going into a brief tangent about what I mean by “housing prices”. When the Bureau of Labor Statistics constructs its measures of housing prices, it does not include any information about the sale prices of homes across America. Buying a home is an investment – you are essentially purchasing infinite years of future rent for an up-front cost. Since BLS is only concerned with current housing prices, housing price indexes are built primarily by analyzing rent and owners’ equivalent rent prices. Rent prices are straightforward – you simply collect data on renter’s monthly housing payments excluding utilities and other amenities that might be bundled with rent. Owners’ equivalent rent is a bit more complex, but essentially involves taking a homeowner’s property and asking “what would the rental price be for this property if the owner were to rent it out?” BLS compiles data on rent prices and applies them to homeowners as “owners’ equivalent rent”. That way BLS can calculate the value for the current price of the house, regardless of what the monthly mortgage is or what the original purchase price of the home was.

Housing’s Contribution to CPI Inflation

The chart above shows the Consumer Price Index (CPI) alongside housing’s contribution to CPI since the turn of the millennium. Housing has made up nearly 50% of the increase in CPI since 2000, no small feat when considering the price crash in 2008. In fact, housing’s contribution to CPI actually marginally increased during the period after the global financial crisis. It took almost four years for housing prices to hit 2007 levels again, but after 2012 housing price increases only accelerated. The post-2008 period was also market with extremely low inflation as a result of weak aggregate demand throughout the economy. Housing prices, alongside healthcare, were the main exceptions to this, and since housing is the largest component of CPI it is the main source of post-2008 inflation. As an aside, it is worth noting that the Federal Reserve’s preferred Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index gives less weight to housing than CPI while giving more weight to healthcare.

Here is the same graph, but showing only shelter’s contribution to inflation. Shelter is the main subset of housing prices that is almost entirely made up of rent and owners’ equivalent rent. The increase in shelter prices represents almost all of the increase in housing prices over the last twenty years, which in turn makes up the majority of the increase in the consumer price index. Though you cannot see it on this graph, housing prices have grown to represent larger portions of the CPI’s basket designed to represent the spending habits of the representation of the median American. Since 2000, shelter has gone from 30% of CPI’s basket to 33%, and housing as a whole has gone from 40% to 42%. So not only is housing increasing in price, but it is taking up a larger share of household budgets.

Relative Price Increases

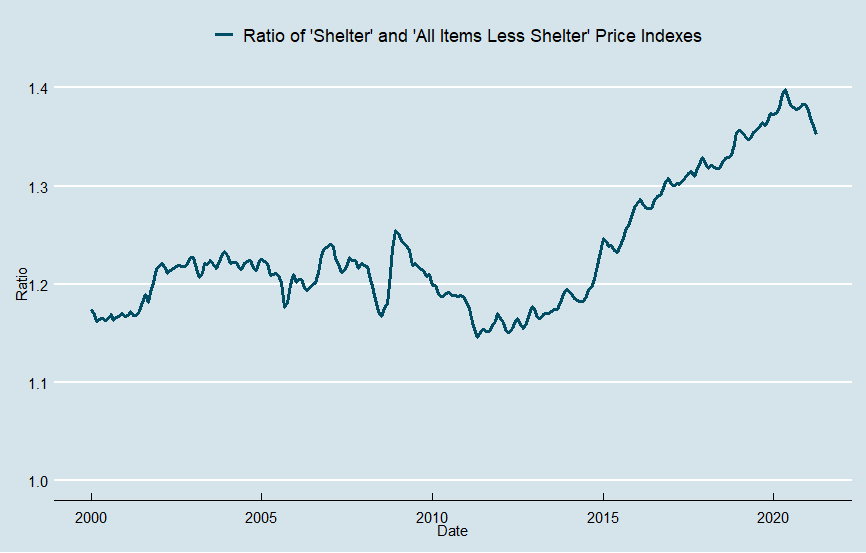

Economist Matthew Klein pointed out that there is little insight in saying that housing is responsible for a majority of the increase in CPI because housing has such a large weight in CPI’s basket. However, it is worth noting that the extreme divergence between shelter prices and non-shelter prices seen in the post-2008 period has never previously occurred in American history. The graph above illustrates the ratio between the shelter and all items less shelter price indexes. When the ratio increases it means that shelter prices are increasing relative to non-shelter prices, when it decreases it means that shelter prices are decreasing relative to non-shelter prices. While the long-run trend clearly shows shelter prices increasing relative to non-shelter prices, these increases were generally fairly low from 1990 to 2010. Since 2010, however, shelter prices have rapidly increased relative to all other prices.

Here is the same graph as before, focused in on the period after 2000. Due to changes in the CPI’s methodology in 1998, comparing data from before 1998 to data after 1998 can cause significant issues (the CPI Research Series can correct many of these, but does not have easily accessible housing data). Even during the housing boom of the 2000-2006 period, shelter prices did not increase faster that non-shelter prices. However, as the economy recovered during the 2012-2020 period shelter prices increased dramatically when compared to non-shelter prices. What could cause this?

The Housing Supply Crunch

It’s all supply.

In the wake of the 2008 crisis, housing starts collapsed. In order to preserve homeowner’s property values, localities became much less willing to zone and permit new housing throughout the United States. The demand for housing is still there, as evidenced by the rapid increase in rental prices throughout the economy, but zoning, setback, parking, and planning restrictions have dramatically cut housing supply. Housing production has only recently caught up with the lowest periods on record before 2008.

Housing investment has also fallen dramatically from nearly 7% of GDP right before the financial crisis to under 5% today. When housing prices are rising at an outsized rate like they have been over the last decade, you would expect residential investment to be dramatically increasing as well. After all, new investments in housing become more profitable the higher housing prices rise. While investment has been increasing, it is nowhere near the peaks of the pre-2008 cycles and would likely need to be substantially higher in order to make up for lost investment from 2008-2020.

The difference between the increase in housing prices and the increase in housing investment illustrates the gap between the supply and demand for housing throughout America. As the population grows, the economy rebounds, and migration patterns change, the demand for housing significantly increases. While this is happening, localities restrict residential investment by stalling and forbidding the construction of new housing units.

The predictable result is an increase in demand for existing housing units, straining existing supply. Vacancy rates for both owned and rented homes across the US have gone down significantly since 2010, a result of increased competition for the limited housing units available. The utilization rate, or the percent of total capacity being used, is rapidly increasing. Americans are pushing up against the capacity constraints of the housing market, and the result is wild increases in housing prices across the board. In highly desirable and supply constrained cities, the problems are even worse.

Regional Variation

The graph above shows a more detailed look at housing price increases across the US by taking the ratio of shelter price indexes from various American cities and comparing them to the all items less shelter index for the whole United States. Essentially, any increase in this ratio represents housing prices for that region increasing faster than non-shelter prices in the total US economy. It is also worth noting that all of the charts are for the city’s associated Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs), not exclusively the cities themselves. So the “New York City” line actually represents the ratio of shelter prices in New York and its surrounding suburbs to all non-shelter prices in the US.

While none of the cities above had shelter become cheaper relative to non-shelter items, Atlanta and Houston came in with the lowest relative increases. San Francisco, Seattle, New York, and Los Angeles all had extremely significant increases in shelter prices. Given these cities’ rapidly growing economies and lack of sufficient residential construction, this should be no surprise.

Here is the same graph as before, but with all prices indexed to 2000 instead of 1985. Again, we can see significant increases in relative housing costs for all cities – especially those with intensive supply constraints imposed by zoning and parking regulations. Los Angeles had the highest relative increase of the group (the data cuts off due to a reorganization of BLS’s regional indexes), followed by Seattle, San Francisco, and New York City.

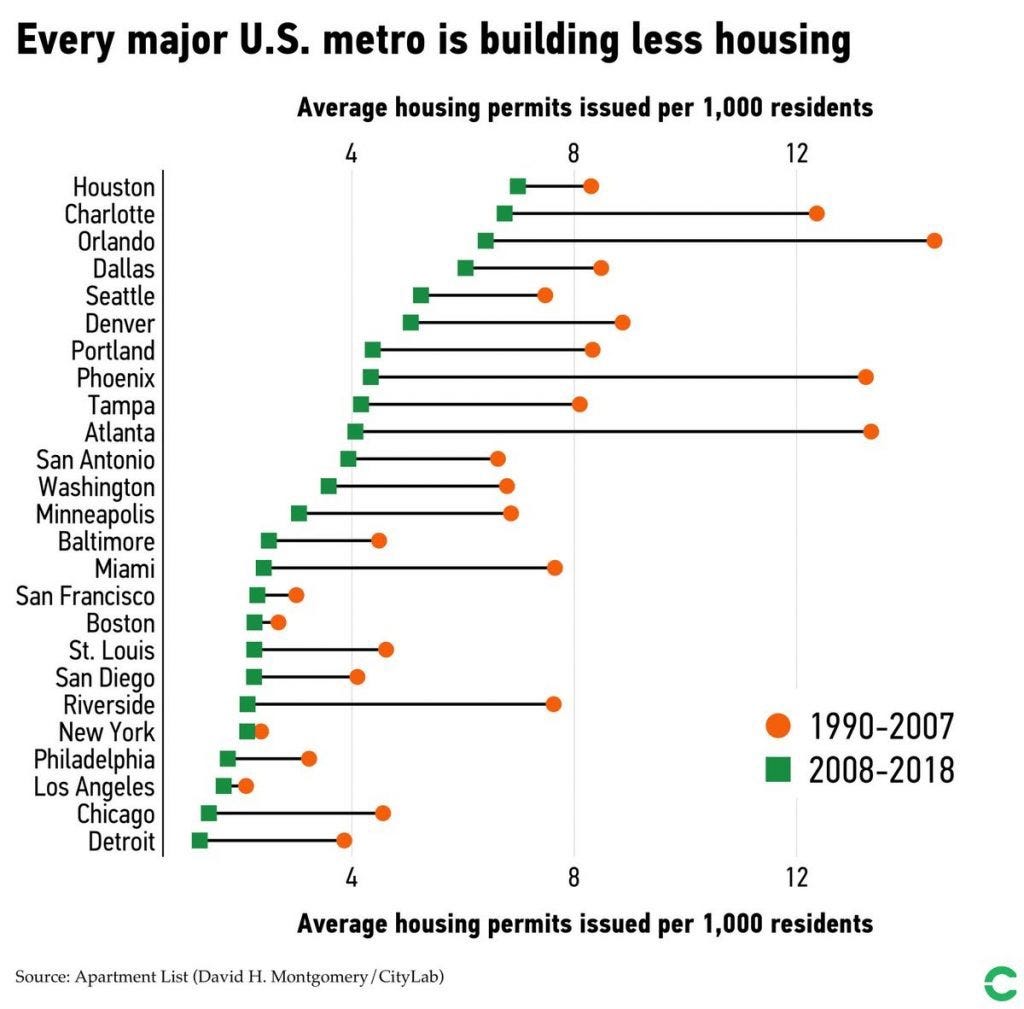

Courtesy of David Montgomery, we can see that the variation in housing price changes across US cities is primarily due to variation in their construction rates – the areas with the largest relative housing price increases in the previous charts (Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco) are generally the areas with the lowest number of permits issued per capita.

Conclusion

Component-level analysis of inflation is absolutely crucial in identifying the capacity constraints within an economy and sectors where demand is rapidly outstripping supply. Today, component-level analysis of inflation in the US shows that housing remains the single largest constraint on US economic growth by a wide margin. This is especially true in America’s largest, most dynamic cities where housing prices increase rapidly as a direct result of these cities’ restrictions on new construction.

Solving the housing crisis in America right now would mean lowering most Americans’ single largest expense and solving the largest supply constraint facing the American economy. It would have knock on effects throughout the economy – combating systemic racism, improving social mobility, boosting GDP, and improving quality of life. A recent paper by Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti estimated that economic growth would have been 30% higher from 1964-2009 if New York City and the San-Francisco Bay Area alone had eliminated restrictions on housing supply. For a given money supply, nothing combats inflation more than drastically increasing output – and easing zoning restrictions is the easiest way America can drastically boost economic growth.

Great analysis. As an owner of rural land and a builder of innovative affordable homes I can testify that I am denied permission to erect houses for rental on my 50 acres of land that is classified 'rural residential' because the zoning requires me to subdivide to create seven blocks and the associated infrastructure to support just seven homes. If the land were zoned 'rural', only one home would be allowed. Effectively, development is restricted to unimaginative large corporations capable of providing land fronting a constructed road for single homes to continue the 'urban sprawl'. If landowners such as myself could build appropriately sized homes for singles, couples and the smaller family units of today, the required increase in supply would be forthcoming. There are better ways to go than mindless continuation of alienating urban sprawl that I describe on my substack, ways and means to build more functional communities to provide better outcomes, in particular for women and children. Planners who are socially conscious need to examine what they are doing and get back to basics to re-imagine what they could be doing. Here in Australia, the basic parameters are laid down at the state level and the results are as you would expect wherever central planning is employed. Abominable. Inhumane.