Understanding Americans' Excess Savings

Diving into Data on Income, Spending, and Financial Asset Distribution to Explore Americans' $2.5 Trillion in Excess Savings

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bureau of Labor Statistics or the United States Government.

Since the start of the pandemic, Americans have socked away an extra $2.5 trillion in so-called “excess savings”. A drop in consumer spending coupled with increased income from stimulus checks and enhanced unemployment benefits resulted in a large pile of household savings. In April 2020 the personal saving rate hit a record 33.8%, absolutely dwarfing the previous record of 17.3% set in May 1975. What Americans do with their savings will define the economy in the coming years.

That’s why it is critical to dig deeper into the causes, composition, and distribution of America’s excess savings. Though government benefits have played a crucial role in buoying the savings rate, they are by no means the only factor. Households aren’t simply keeping more cash on hand either—a lot of excess savings have been used to pay down debt or replace borrowing. Nor are households the only ones saving money—corporations have been shoring up their balance sheets with excess savings since late 2020. And while low-income Americans benefitted the most from the expansion of government transfers, it is high-income Americans that have accumulated the largest stockpiles of cash. These facts are critical to understanding how, or if, Americans will spend their excess savings.

A Penny Saved…

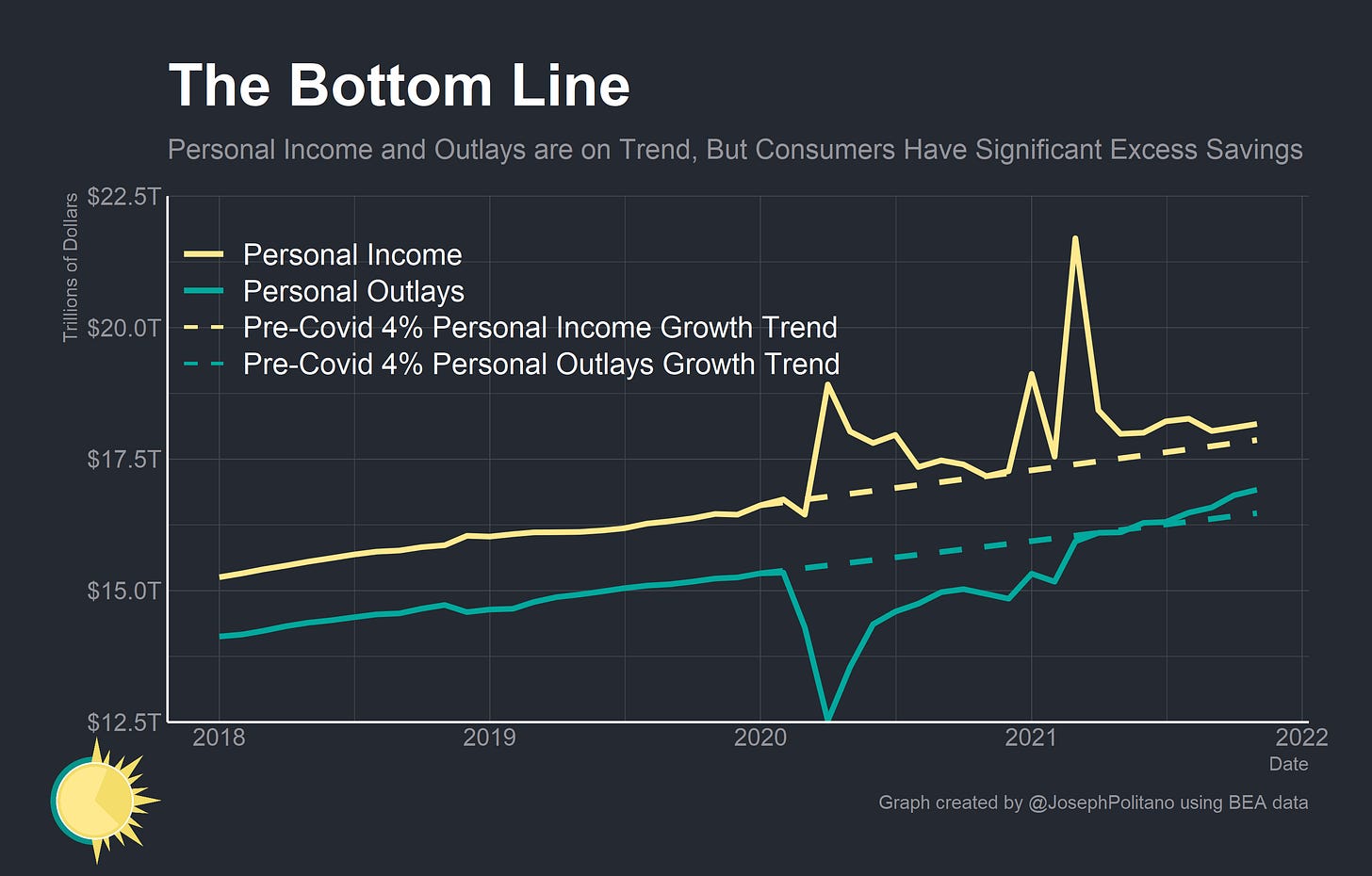

The pandemic represented an unprecedented shock both to personal income and personal outlays. When COVID hit the United States, Americans immediately dramatically cut back their spending. When the federal government disbursed trillions of dollars in stimulus, Americans’ incomes immediately shot up. It took a full year for aggregate spending to return to the pre-COVID trend, and the second and third rounds of stimulus checks kept personal income above trend throughout most of 2021.

The result was a massive mechanical rise in American’s personal saving rate. Starting at around 7.5% in late 2019, the personal saving rate rocketed above 30% and remained above 10% until August of 2021. In aggregate, Americans were keeping between 10% and 30% of their disposable personal income throughout the pandemic—and the saving rate has only recently normalized.

Now, this rise in personal incomes and the personal saving rate is a mechanical result of deficit-financed stimulus spending. Public sector deficits are private sector surpluses, meaning that a net increase in deficit spending will also represent a net increase in private sector financial balances. Or to put it simply, for the government to owe additional money—an increase in the deficit—the private sector must be owed additional money—an increase in private sector surpluses.

In normal times this does not really matter due to the Federal Reserve’s monetary offset. In theory, whenever the federal government enacts expansionary fiscal policy the Federal Reserve simply tightens monetary policy to keep aggregate income growth stable and prevent inflation. In other words, the Federal Reserve offsets increased public sector borrowing by raising interest rates to curb private sector borrowing. COVID is not normal times, however. The Federal Reserve chose to limit their monetary stimulus so as to not drop short term interest rates below zero while committing to accommodative monetary policy for the near future. Essentially, they announced that they would not be offsetting fiscal stimulus for the duration of COVID. Stimulus money therefore directly increased total household income and personal savings.

The increase in personal savings is not all about increased income, however. The chart above shows the cumulative deviation from trend in disposable personal income and personal outlays since the start of the pandemic. Please note that these figures are derived from the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s headline seasonally-adjusted personal income data, so they are not perfectly accurate. Think of them only as approximations.

Since the start of the pandemic, Americans have spent approximately $1 trillion less than the pre-COVID trend and have earned approximately $1.4 trillion more than the pre-COVID trend. Total excess savings are approximately $2.5 trillion. Incidentally, excess savings have been shrinking over the last few months as total consumer spending runs above the pre-pandemic trend.

By disaggregating personal income and outlays into their component parts, we can examine exactly what is driving the jump in personal saving. Please note that in the above chart a positive number indicates that the component increased aggregate personal savings and a negative number indicates that the item decreased aggregate personal savings. So “personal consumption expenditures” are listed as a positive number because the cumulative decrease in personal consumption expenditures resulted in increased personal savings while labor income is listed as a negative number because the cumulative decrease in labor income resulted in decreased personal savings1. Adding together all the positive contributions and subtracting the negative contributions equals total excess savings.

First, it is obvious that increased government transfers—stimulus checks, enhanced unemployment benefits, and child tax credit payments—are single-handedly pushing savings up the most. Since the pandemic stimulus programs represented extreme upward deviations from the trend growth rate of government transfers, they show up as having a large cumulative affect on excess savings. The cumulative reduction in personal consumption expenditures (household spending on goods and services) also explains a large chunk of increased savings. Either one of these items is more than enough to offset the reduced labor income and capital/proprietor’s income that households have received since the start of the pandemic. Decreased interest payments have pushed excess savings slightly higher while increased taxes pull savings marginally lower.

At this point, it is worth examining what personal saving actually means in the National Income and Product Accounts. Personal saving is simply total income minus total outlays, which leaves a lot of ways for saving to manifest. That includes increased bank account balances, additional retirement contributions, cryptocurrency purchases, paying down the principal of mortgages or other household debt, and even home remodeling (technically categorized as “residential investment”). In other words, it is not like there is precisely an additional $2.5 trillion sitting in household bank accounts because the personal saving rate has increased by $2.5 trillion.

Additionally, households are not the only members of the private sector. Business and non-profits have also increased their savings since the start of the pandemic. Undistributed corporate profits (analogous to “corporate saving”) are up significantly in 2021. Note that this is not “total corporate profits” but rather “corporate profits not distributed to shareholders”. One reason why capital income growth has been below trend since the start of the pandemic is that businesses are currently distributing a smaller share of their profits in order to shore up their balance sheets given pandemic uncertainty.

Finally, it is worth remembering that aggregate saving rate to increase in one sector it must generally decrease in another. The last six months have seen a dramatic reduction in household saving and increase in corporate saving as consumers spend more of their money and corporations distribute a smaller share of their profits. We have also seen a large decrease in the federal budget deficit, mechanically reducing private sector surpluses. However, without the government running a surplus private sector cash savings cannot decrease (though it is worth remembering that not all personal savings are financial and that governments will likely need to run large deficits in the future in order to counteract a declining real interest rate).

…Is A Trillion Earned

So far, we have only examined excess savings in the aggregate. But to truly understand how excess savings are affecting the economy, it is critical to examine how those savings are distributed throughout the economy. For this, the Federal Reserve’s Distributional Financial Accounts are an indispensable tool.

By looking at liquid financial assets (in this case the sum of checkable deposits, currency, and money market fund shares) we can closely examine how much households at different income levels have saved since the start of the pandemic. All but the bottom 20% of households have accumulated significant additional liquid financial assets, but the top 1% have seen their liquid financial assets increase by a staggering 150%.

That number is even more astonishing when you remember that the top 1% already held an extremely large amount of liquid financial assets before the pandemic. As a result, the top 1% has accumulated an additional $1 trillion in bank deposits, currency, and money market fund shares since the end of 2019. The next 19% have accumulated another $1 trillion with all other income levels adding less than $1 trillion combined.

Eagle-eyed readers will note that the total change in liquid financial assets is higher than the total $2.5 trillion in excess savings we previously identified. Keep in mind that this is measuring total change in financial assets while the $2.5 trillion is excess (that is, above-trend) savings. Also keep in mind that excess savings could have been socked into paying down debt or new investments, not simply accumulating extra cash. Finally, remember that an increase in liquid financial assets can come about without additional savings by converting other financial assets to cash (like through the Federal Reserve’s Quantitative Easing bond-buying program). These are complimentary, not analogous, data points.

Another piece of complimentary data comes from the exemplary research out of the JPMorgan Chase Institute’s Household Balance Pulse Report. They see higher percent increases in checking account balances of low-income households but higher nominal increases in checking account balances of high-income households. In other words, the majority of aggregate excess savings are held by the top earners even though low-income households have seen a higher percentage increase in savings. This data also excludes liquid financial assets held outside of checking accounts, likely missing some cash held by high-income households in savings accounts or money market funds.

One area where excess savings may be showing up more for middle and low-income families is in the reduction of outstanding debt. Consumer credit growth—which includes credit cards, student loans, auto loans, and more—was basically stalled in its tracks by the start of the pandemic. This is especially beneficial to low-income households who have seen the fastest rate of consumer credit growth over the last few years. A lot of this is likely due to reduced credit card debt and a slower growth rate of outstanding student loan debt (buoyed by the pause on student loan interest). At any rate, it is clear consumers used some of their excess savings to pay down debt or pay in cash instead of credit.

Conclusions

What do excess savings mean for America’s short term economic outlook? For one, I am extremely skeptical of claims that excess savings are hampering employment growth or keeping workers out of the labor market. Mark Zandi, the Chief Economist at Moody’s Analytics, claims that as excess savings deplete “the financial pressure to return to work is thus quickly intensifying”. I flatly do not see it this way. The median checking account balance of households in the bottom 25% is up a meagre $363 from its level in 2019—hardly enough to sustain a long period of time without labor income. Even before the pandemic, the vast majority of Americans did not have sufficient savings to cover even 3 months of expenses (personal finance experts usually recommend an emergency fund large enough to cover 3-6 months of expenses). Fundamentally, the majority of excess savings are held by high income households who retained their jobs throughout the pandemic while the majority of government benefits went to low income households who may have lost their jobs during the pandemic.

Most attempts at analyzing the effects of pandemic stimulus spending seem to miss the mark either by over-aggregating fiscal transfers or by treating stimulus money as equivalent to windfall earnings. Take this Goldman Sachs research note that ascribes half of the drop in labor force participation to increased fiscal transfers due to the correlation between fiscal transfers and the drop in labor force participation. Unsurprisingly, countries that experienced a large drop in labor force participation tended to increase fiscal transfers because more unemployed workers means more spending on unemployment benefits, not because unemployment benefits created unemployed workers. Or take this Richmond Fed economic brief that uses data on the employment outcomes for lottery winners to estimate the effects of fiscal benefits on aggregate employment levels. I shouldn’t need to tell you that getting unemployment insurance is not like winning the lottery.

While most of the excess savings is held by high-income Americans, who do not have a particularly high marginal propensity to consume, I do think that high income earners will consume more of their excess savings than they would under a traditional increase in wealth. For one, high-income households have been stockpiling extremely liquid financial assets, an indication that they may only be waiting for a good opportunity to spend their money. For two, historical episodes of excess savings (like the post-WWII era) have seen a slow but steady drawdown of excess savings over the following 5-10 years. For three, polling from earlier this year showed that consumers intended to spend down some of their excess savings, and personal consumption expenditures have already exceeded their pre-COVID trend.

Where high-income households spend their savings will also prove just as important as when they spend their savings, especially given high inflation and the disproportionate spending on goods throughout the economy—but I will leave that for a future blog post.

Readers who are familiar with the National Income and Product Accounts will note that I condensed “personal taxes” and “contributions for government social insurance” into simply “taxes” and condensed “personal income receipts on assets” and “proprietors' income” into “capital/proprietor’s income”. This was done to make the chart cleaner and improve data communication. “Personal current transfer payments” (transfers to the government and the rest of the world) were also excluded due to their negligible effect on excess savings.

Personal savings (FRED data) is right back where it started, implying that this $2.5 trillion is fictitious. Where is the disconnect??

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PMSAVE

Is there any connection to the surge in housing demand? It’s been attributed to lower interest rates but I wonder if savings impacted it as well. Would high income savers be likely to target housing?