How Tariffs Are Breaking US Trade

A Detailed Look at How US Trade Flows Are Unraveling Amidst Trump's Trade War

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing, you’ll join over 68,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

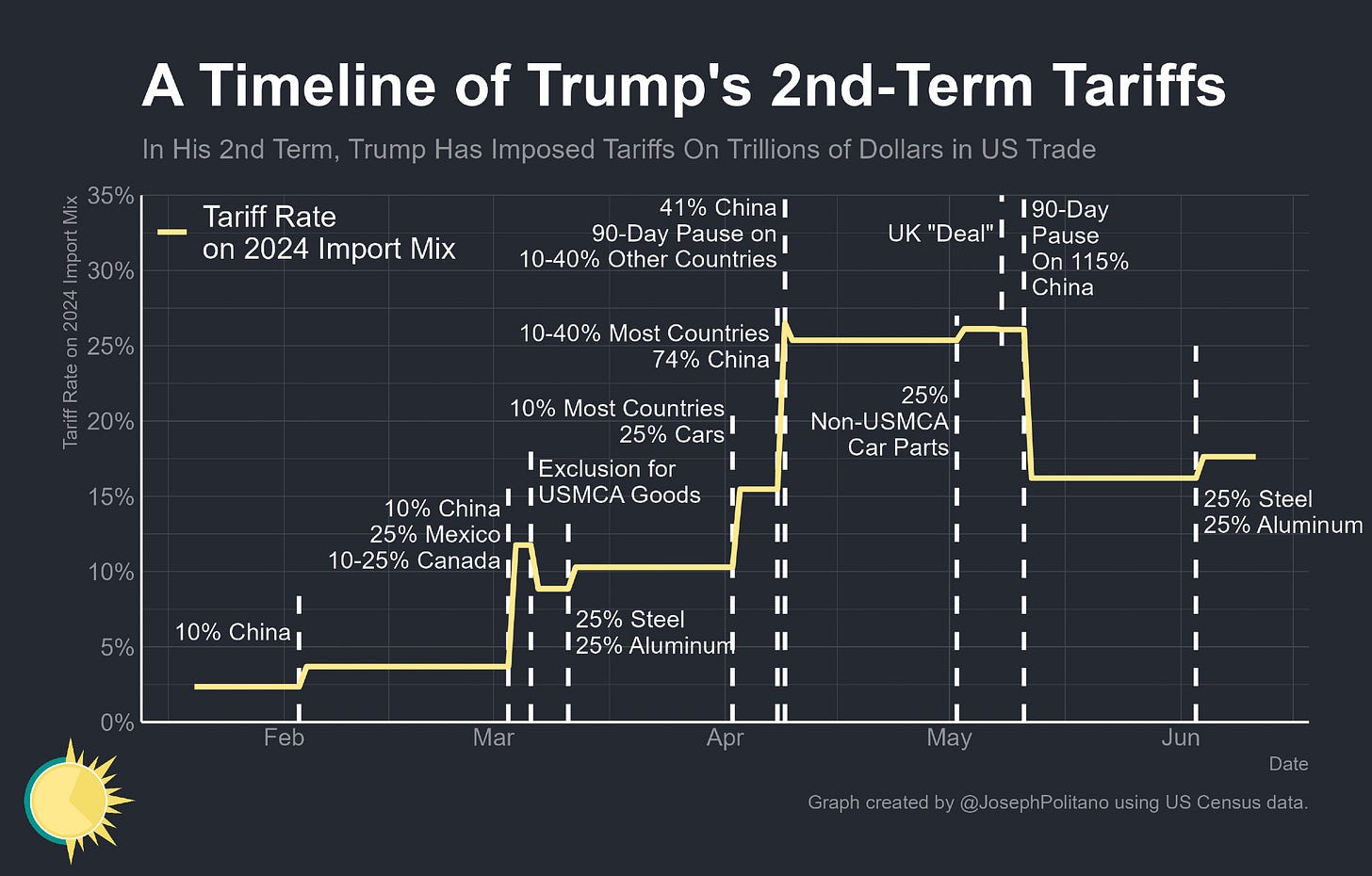

Since the start of his second term, Donald Trump has begun the largest trade war in modern American history—at peak, tariffs had risen to more than eleven times their 2024 levels, and today they remain more than seven times higher than last year even as Trump’s 115% China tariffs and much of his April 2nd tariffs remain paused. Trump has also been constantly manipulating those tariff rates since coming into office, unable to go more than 28 days without another major change. That pattern continued this month, when he suddenly announced a doubling of tariffs on steel & aluminum, and it is almost certain to continue next month as the 90-day pause on April 2nd country-level tariffs expires.

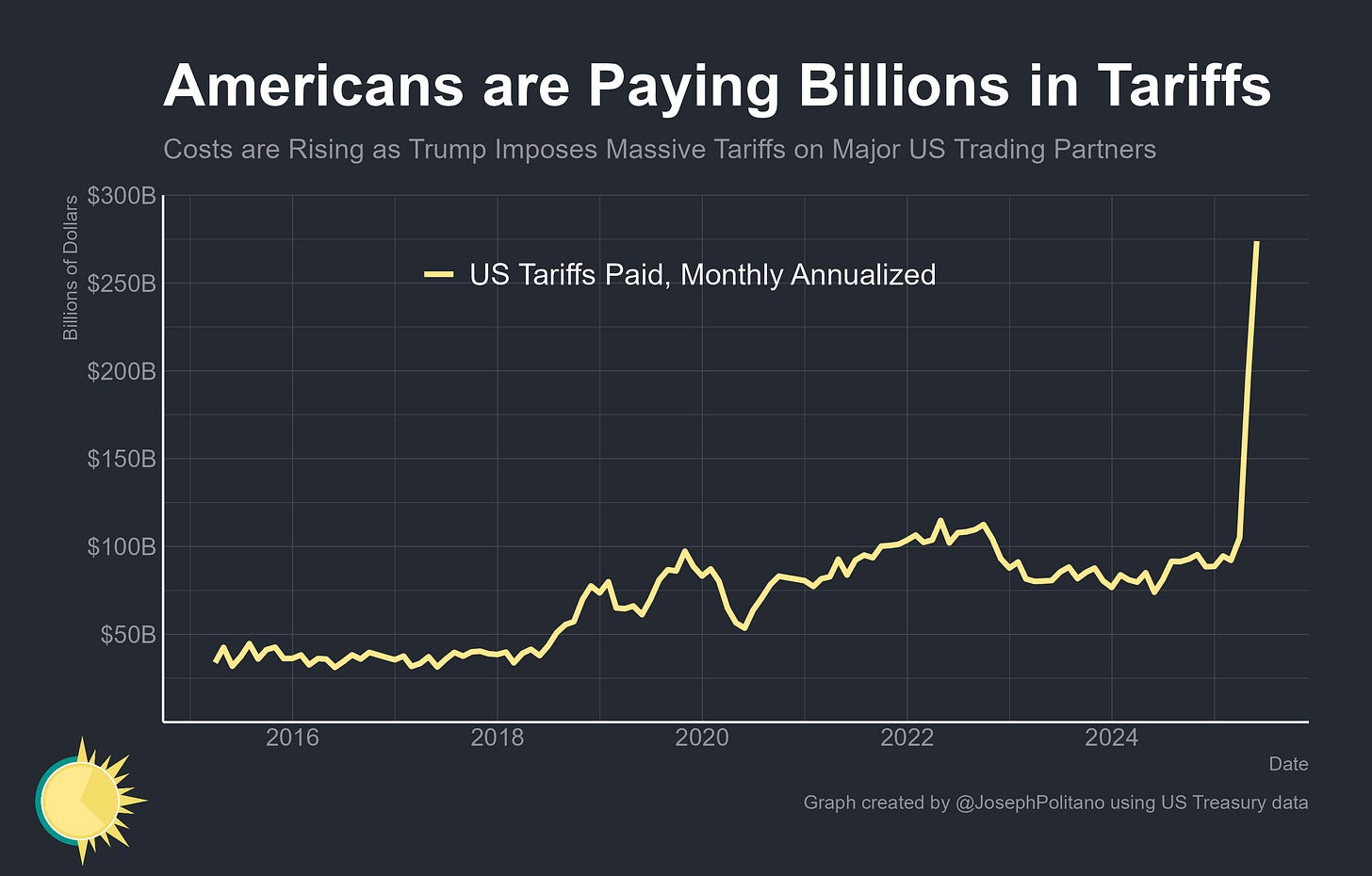

Americans are now paying the costs of those tariffs, in record amounts—Treasury statements indicate that Customs and Border Protection collected $23B in tariffs during May, nearly triple what they collected last year. By revenue, this represents the largest US tax hike in more than 30 years, and it is all concentrated in the haphazard imposition of one of the most economically destructive taxes possible.

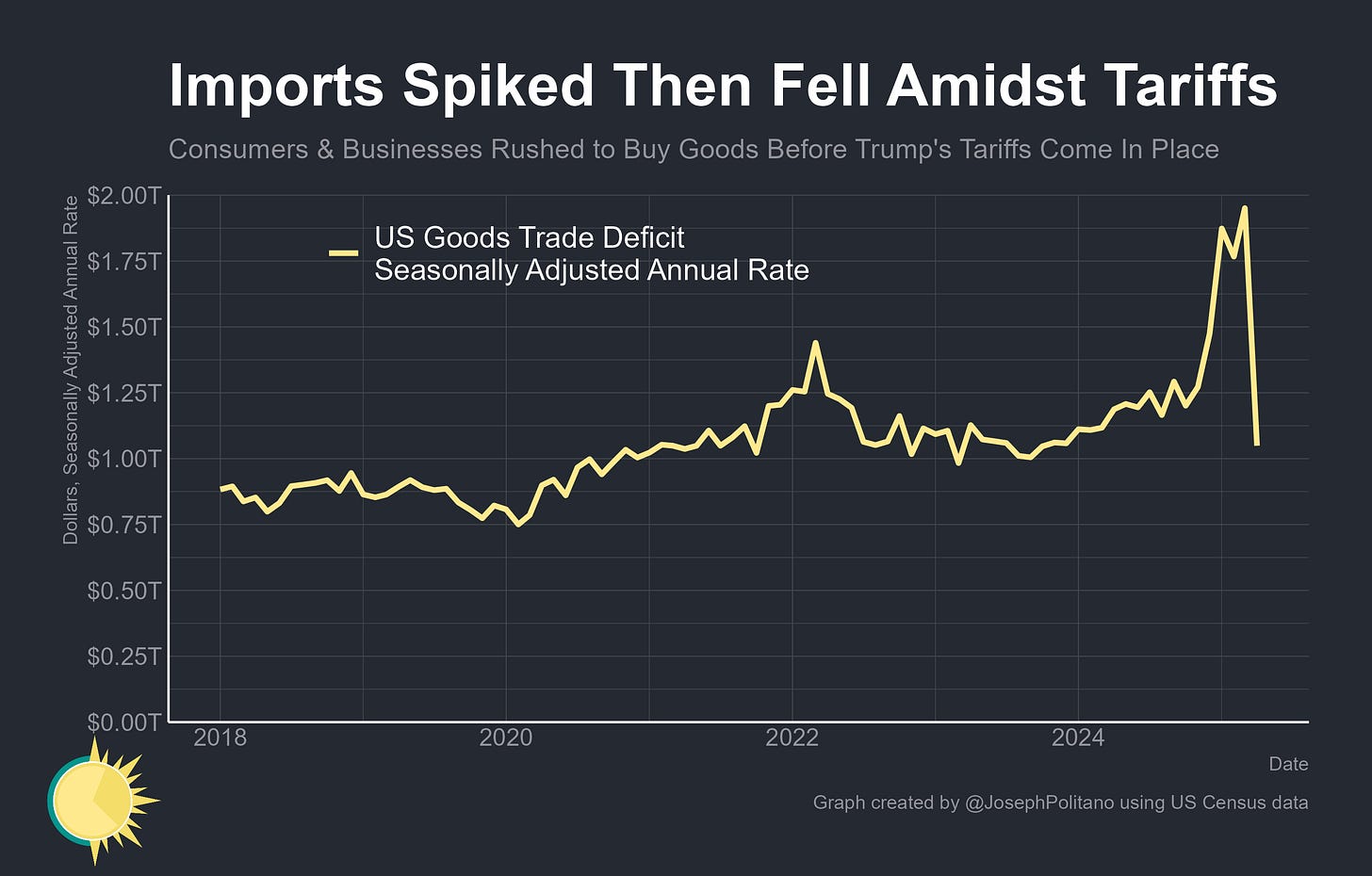

This historic increase in trade restrictions, coupled with high volatility and uncertainty, has wreaked havoc on US trade flows over the last four months. Between November and March, the US goods trade deficit surged 53%, before dropping 46% in April as the largest of Trump’s tariffs began to take effect. This is historically unprecedented trade volatility, with the March-to-April change in the trade deficit being the largest on record by an incredibly wide margin. That combination of high trade restrictiveness and extreme policy uncertainty is now pushing American trade to the breaking point.

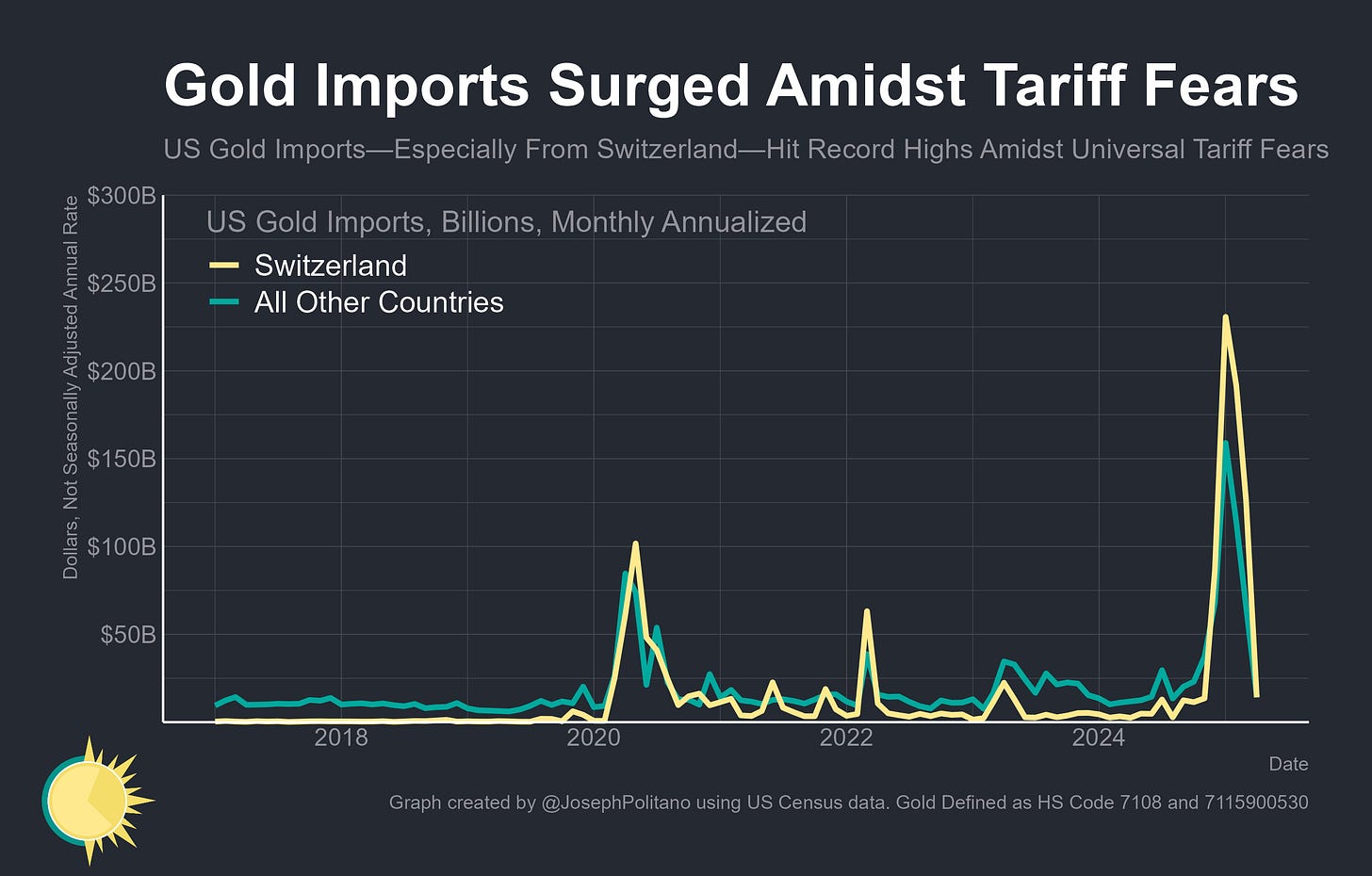

The Largest Contributors to the Import Surge

Although virtually every part of US trade has been affected by these tariffs, the shifts in the overall trade deficit have been dominated by only two types of goods: pharmaceuticals & gold. US imports of gold spiked to record highs early this year as uncertainty spiked gold prices and fears that gold would not be exempted from tariffs caused a rift between American and European prices. The end result was a massive surge in gold imports, especially from Switzerland, as panicked consumers searched for safety and financial firms worked to arbitrage the American price premium. That surge in imports rapidly dissipated when it became clear that gold bullion would be exempt from the tariffs, leading to a historic drop in imports during April. Yet this is a great example of the costs of tariff uncertainty, as exempting gold imports from the get-go would have avoided much of this panic buying.

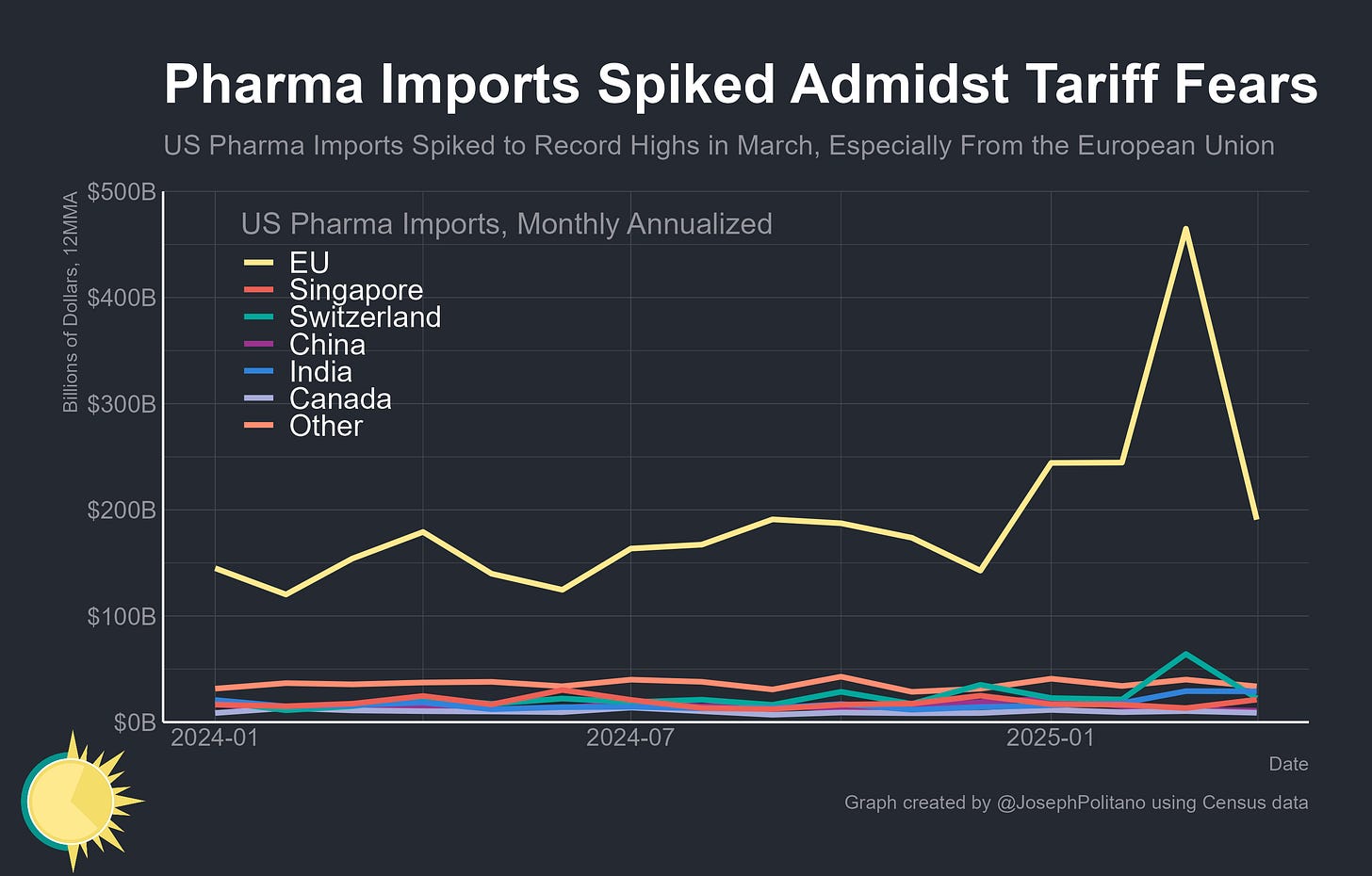

The second major contributor to recent historic shifts in the trade deficit has been pharmaceuticals, where imports peaked at 142% above their 2024 levels before dropping. Drug imports have been mentioned as a key tariff target for months, and while they have so far remained exempt from almost all of Trump’s tariffs, pharmaceutical companies are not taking any chances and stocking up as much inventory as possible. The vast majority of that import surge has come from the European Union, home of research and manufacturing hubs that have long been America’s number one foreign source of medicine—and they’ve been particularly concentrated in Ireland, where many drug multinationals manufacture for tax avoidance purposes.

America’s Collapsing Trade With China

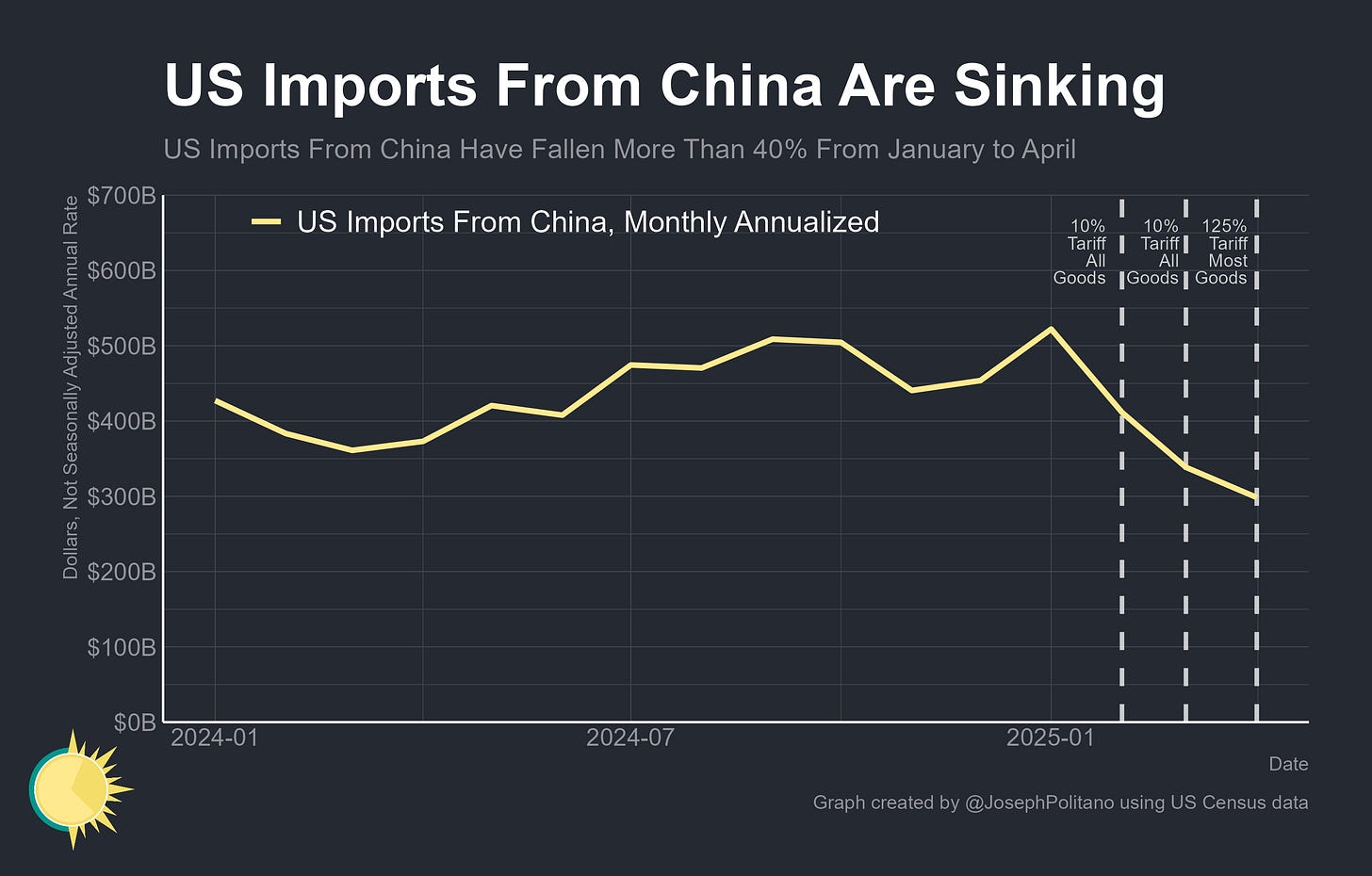

The largest tariffs America has implemented are those on China—at peak, tariffs on most Chinese goods were a staggering 145%, and even now they sit at a historically unprecedented high of 30% for most goods. To put the intensity into perspective, half of all April tariff revenue was collected from Chinese imports. Those tariffs have dramatically reduced the amount of direct trade between the world’s two largest economies, with US imports from China dropping more than 40% between January and April, reaching the lowest levels since March 2020.

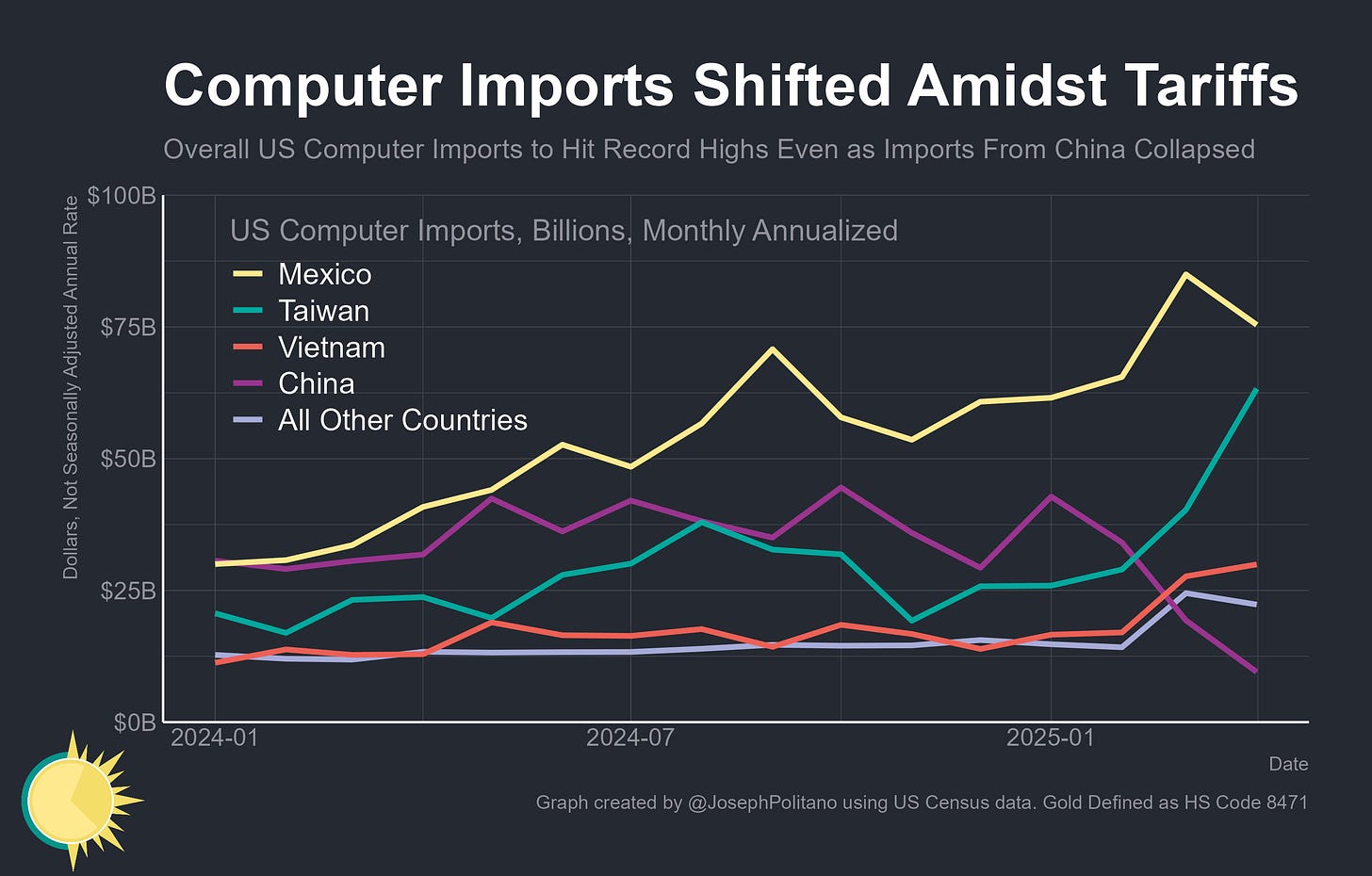

That drop in Chinese imports was led by the country’s large consumer electronics sector, which has long been the world’s primary source of technological devices. US imports of Chinese computers are down 70% compared to last year, with laptop imports dropping to the lowest level in more than 20 years. Imports from Taiwan, Mexico, Vietnam, and a few other countries (like Thailand) have largely made up the slack but are still collectively struggling to meet America’s ravenous demand for computers.

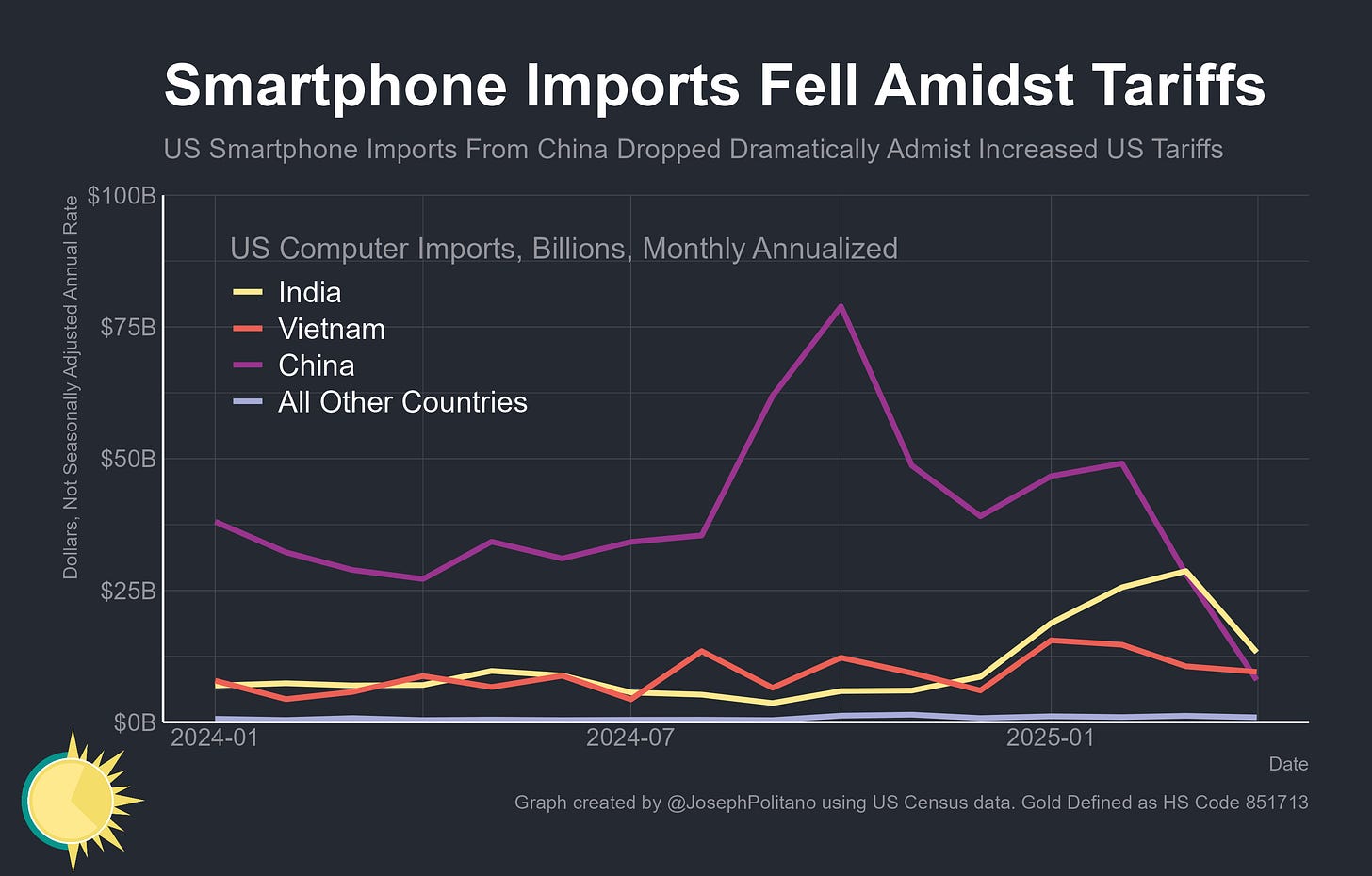

Likewise, US smartphone imports dramatically tanked as tariffs on China ramped up, with imports also dropping 70% compared to last April. America instead bought more phones from India and Vietnam, with both countries surpassing China as a source of imports in the last two months. This largely represents the decision-making of Apple, the country’s dominant phone brand, which has long worked to partially diversify its supply chains out of China and is now putting in overtime to assemble most American phones in its Indian & Vietnamese factories. Yet right now, those non-Chinese-made phones are still nowhere near enough to make up for the shortfall caused by the China tariffs. That’s despite those non-Chinese phones remaining exempt from all tariffs, as Trump has made no moves to implement his long-promised semiconductor and electronics tariffs.

Looking at Other Import Categories

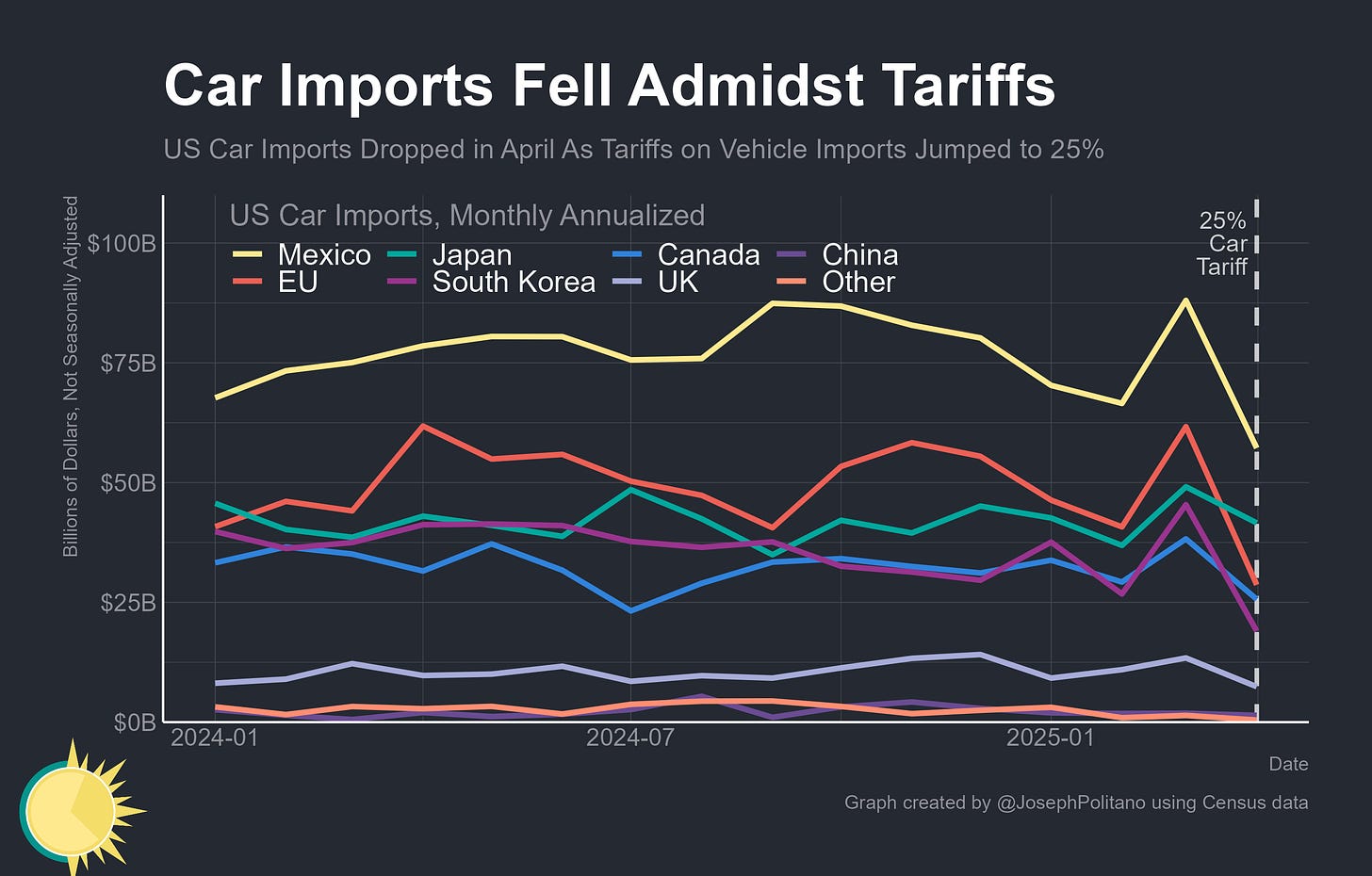

Yet Trump has imposed other universal sectoral tariffs, and those are already having significant impacts on US trade flows. First is the 25% tariff on all foreign cars, which went into effect on April 2nd and affects roughly $250B in American imports. Those tariffs caused a rapid surge in vehicle imports through March as consumers/dealerships rushed to buy cars before the tariffs went into effect, and then imports dropped significantly in April when the tariffs officially began. Indeed, in the most recent data, total US car imports were down 33% compared to last year. That drop in imports was seen across almost all major US trading partners but was concentrated in cars from Mexico, the EU, Canada, and South Korea.

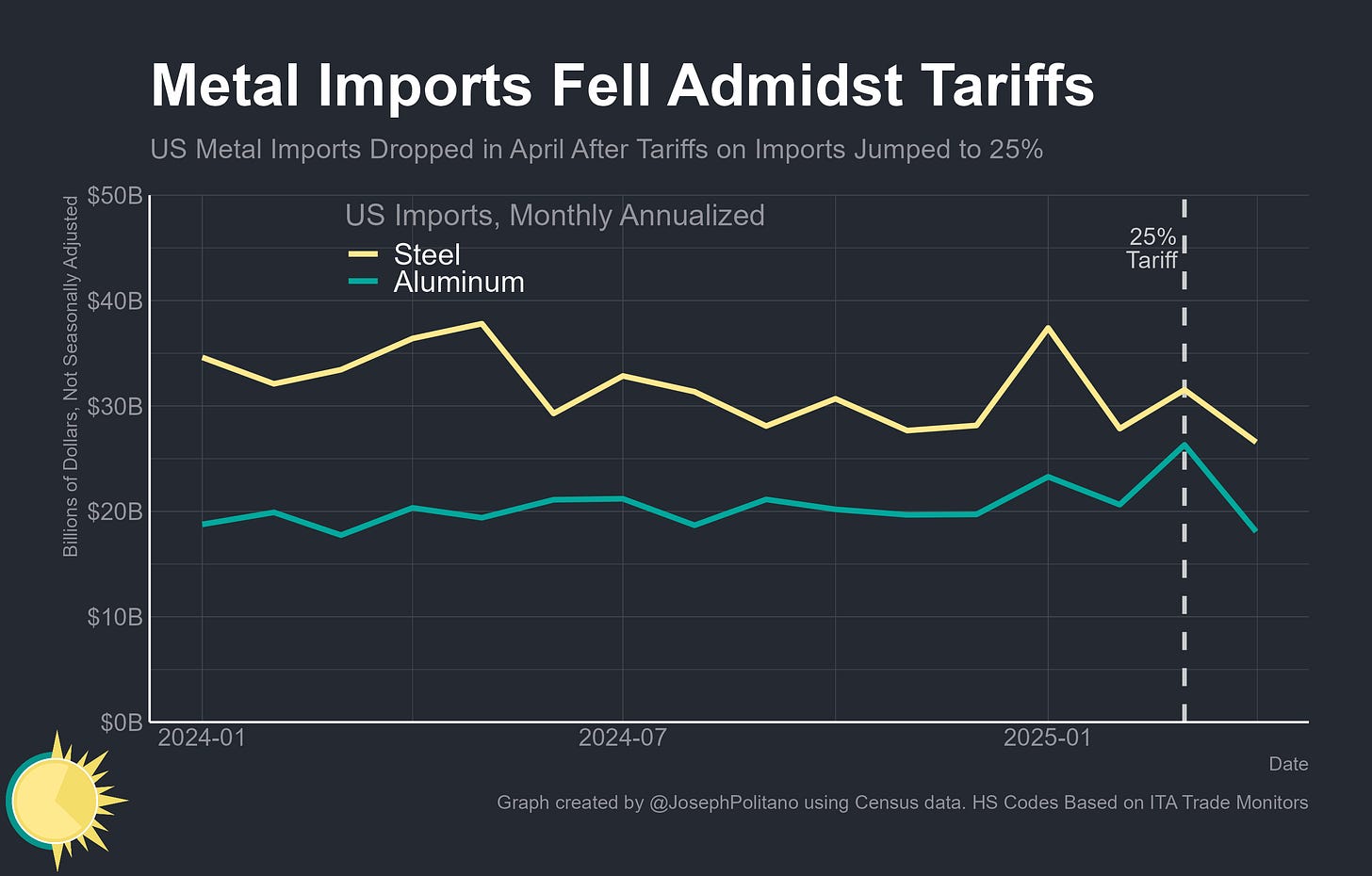

Then there is the 25% tariff on all steel and aluminum imports that began in March and doubled to 50% in June. The data we have through April shows a significant decrease in aluminum imports after some frantic tariff frontrunning in March, with similar but more muted effects for US steel imports. The imposition of 50% tariffs will likely further reduce metal imports, but at an even higher cost to the wider population of downstream manufacturers, construction companies, and consumers that rely on affordable materials.

The Pain in Exports

In addition to damaging American imports, the trade war has also had deleterious effects on US exports. Usually, this happens through rising exchange rates, as tariffs cause the dollar to appreciate and make US exports less competitive in the short term, but since April the dollar has actually depreciated heavily as part of the broader “sell America” trade.

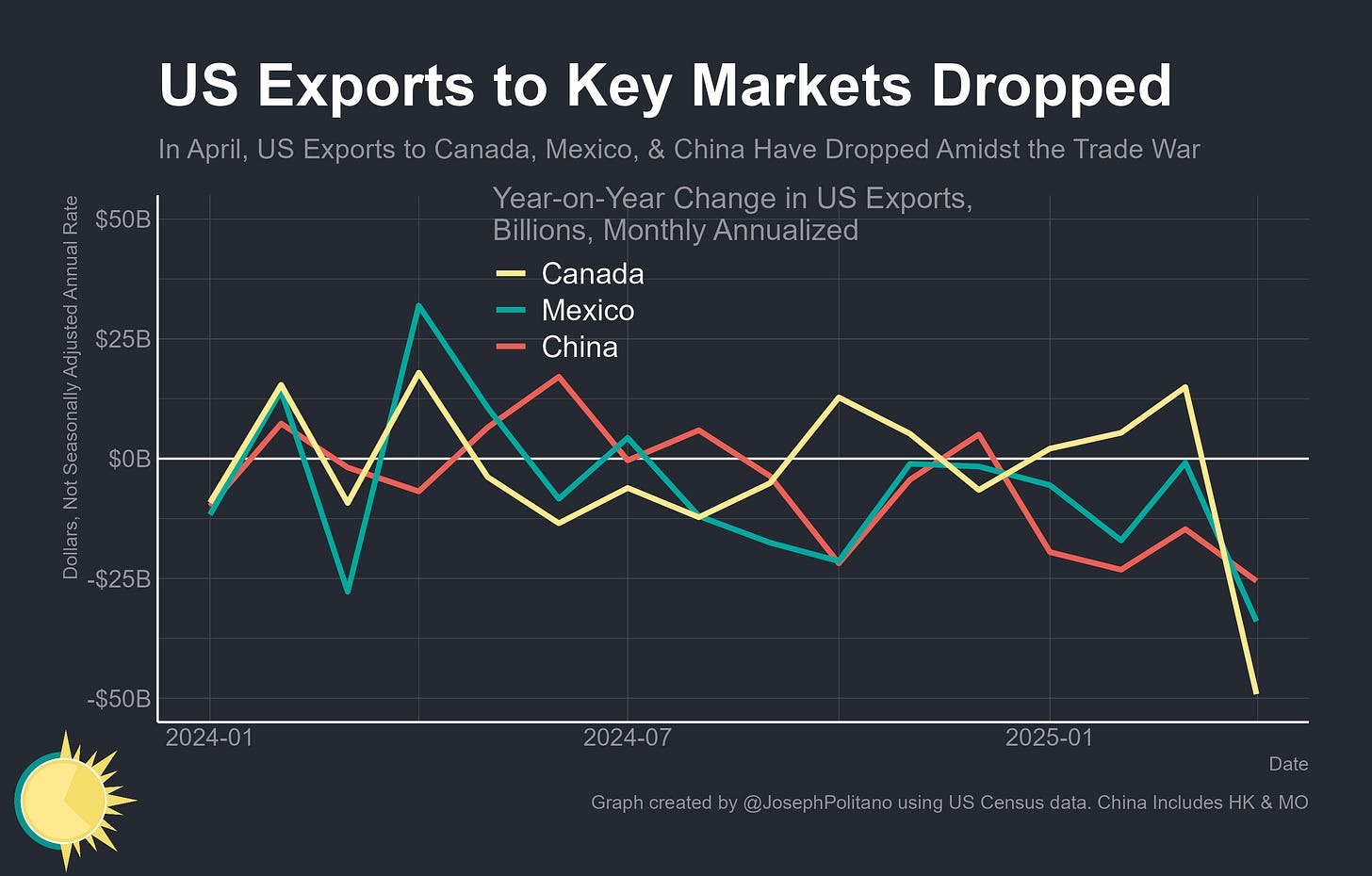

The drop in US exports has instead come primarily from retaliatory tariffs and hardening foreign public opinion to US-made goods. Indeed, overall US exports have held steady amidst the trade war; it’s exports to a key subset of trading partners that have tanked—gross exports to Canada have dropped by nearly $50B annualized, and gross exports to both China and Mexico have dropped by more than $25B.

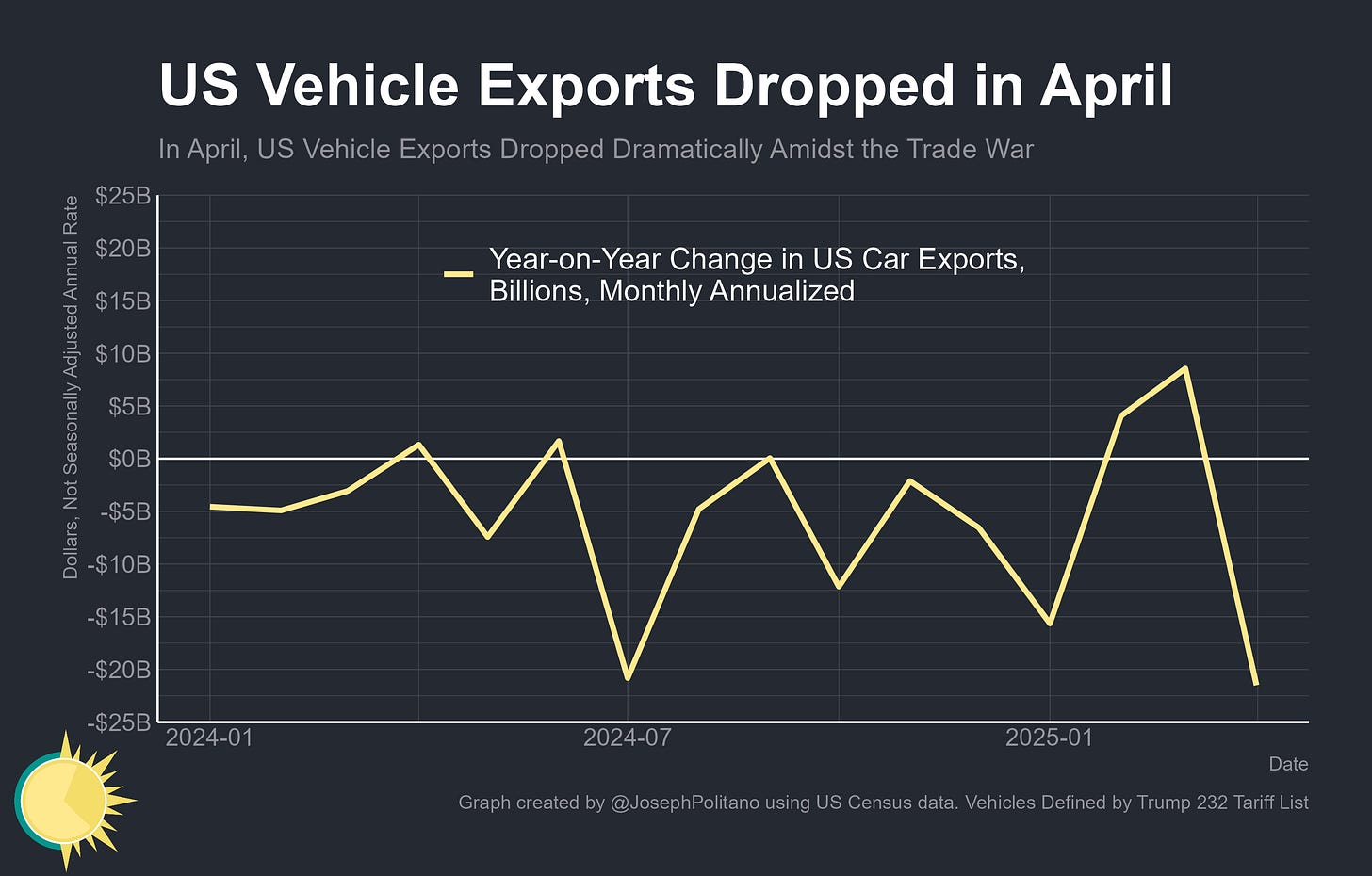

By product, the largest hit to US exports came in the vehicle sector, which saw a more-than-$20B-annualized drop compared to last year. For context, that is the single-largest drop in US car exports outside of the initial onset of COVID-19. Foreigners are proving less likely to want American vehicles, and US auto manufacturers are looking to redirect as much production as possible towards domestic demand in order to minimize their need to import. Expect even more volatility in America’s vehicle trade soon, as the effects of car parts tariffs will begin showing up next month, and Trump has recently been mulling over further increases to US auto tariffs.

Conclusions

Today, no other wealthy country has tariffs as high as America, no country has experienced a comparably rapid decrease in trade openness, and no country has ever changed policy course so frequently. Trump’s first-term trade war, which looks masterfully planned and incredibly minor in comparison, still imposed significant costs on the US economy. It is no wonder that his second-term trade war has proven so destructive.

Over the last two months, Trump has at least managed to avoid any tariff escalations on the scale of early April, but he has also not solidified any major tariff reductions. More than two-thirds of the way through Trump’s 90-day tariff pause for countries besides China, the US has only been able to ink one small nonbinding trade “deal” with the UK. The next few weeks will provide crucial signals for how Trump wants to operate moving forward—will he kick the can down the road for another 90 days, make some face-saving reductions in overall tariff rates, or reimpose much of his April 2nd tariff threats? Either way, Trump has already done unprecedented damage to US trade relationships, and a high-tariff America remains the new normal.

Indeed, the “deal” with the UK is merely a “deal to work out a deal.” So far, Trump’s “trade wars are good annd easy to win” record is about 0 for 90. Ninety being approximately the number of nations on which Trump imposed tariffs April 4. Any team with that kind of record would see its manager fired.

Next post should be why these substack comments are so bad