The 'No Hire' Economy

US Job Growth has Zeroed Out as Hiring Rates Sink, Hitting Young & Low Income Workers the Hardest

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing, you’ll join over 75,000 people who read Apricitas!

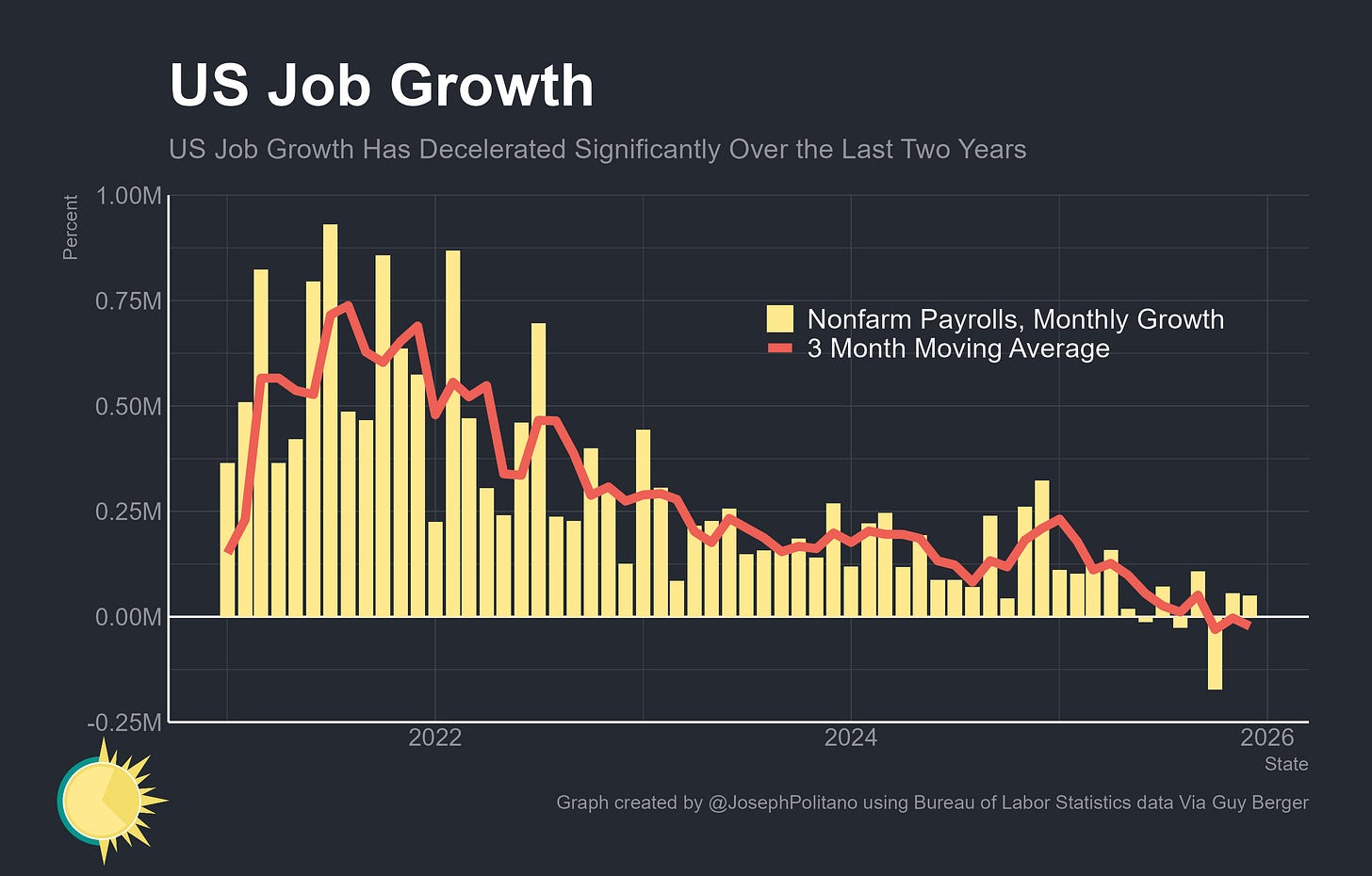

The US job market slowed down significantly in the latter half of 2025, with the country adding functionally zero jobs over the last 5 months as the unemployment rate ticked up to some of the highest levels since early 2021. Averaged across the entirety of 2025, the US added only 44k jobs per month, the lowest since 2020 and lower than any year during the 2010s. It’s a dramatic reversal for a labor market that was setting modern hiring records only a few years ago.

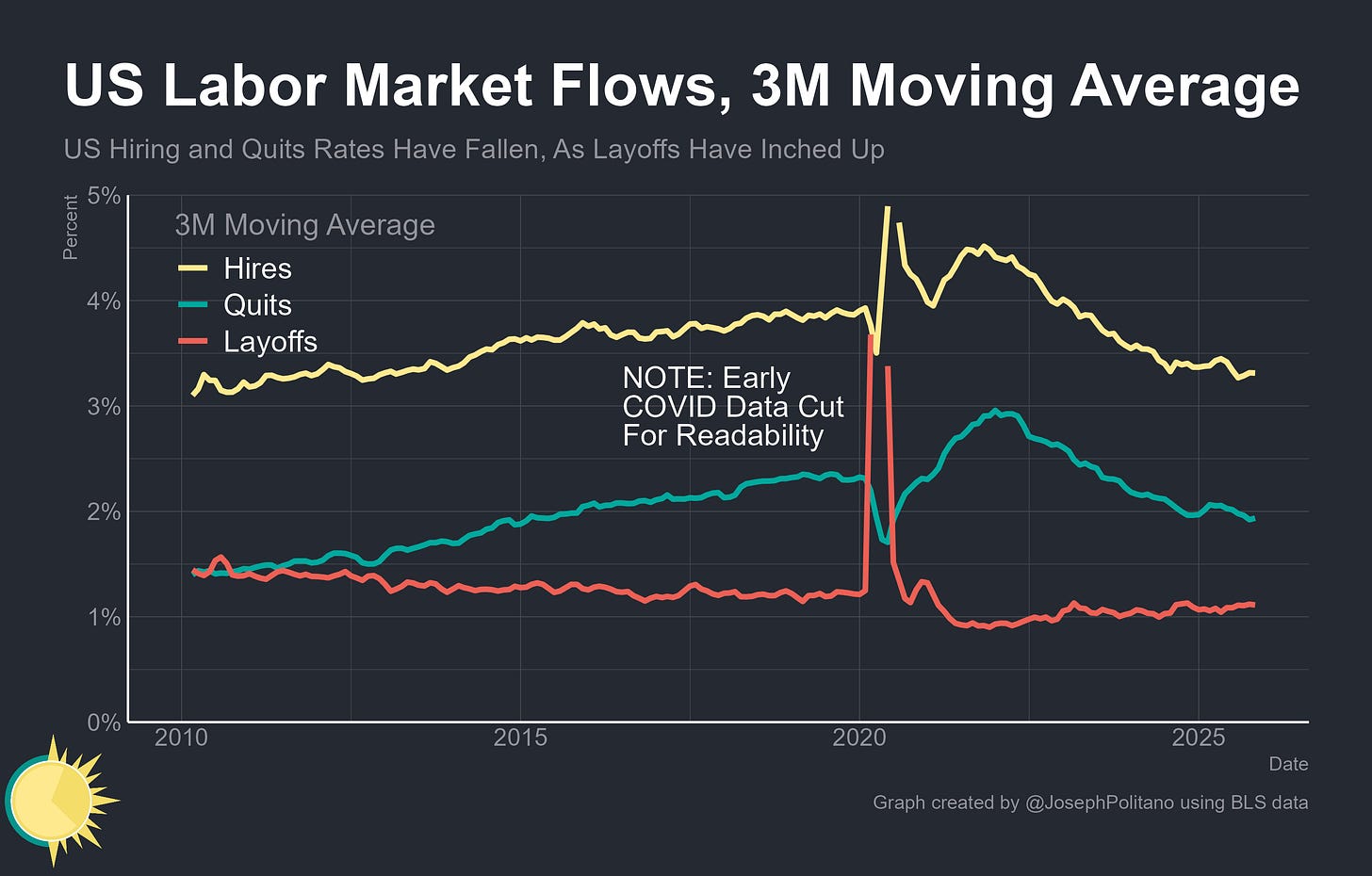

In 2021 and 2022, the US economy experienced the “Great Resignation” (or perhaps more accurately the “Great Reshuffling”), where tens of millions of workers quit their jobs and were hired into better-paid positions in other companies. Then, between 2023 and 2024, the US economy settled into a “low hire, low fire” equilibrium as employers were not onboarding many new workers, but were also laying off fewer workers than pre-pandemic. That has now given way to a “no-hire” economy—layoffs have inched up towards their pre-pandemic average, but hiring has sunk all the way down to 2013 levels.

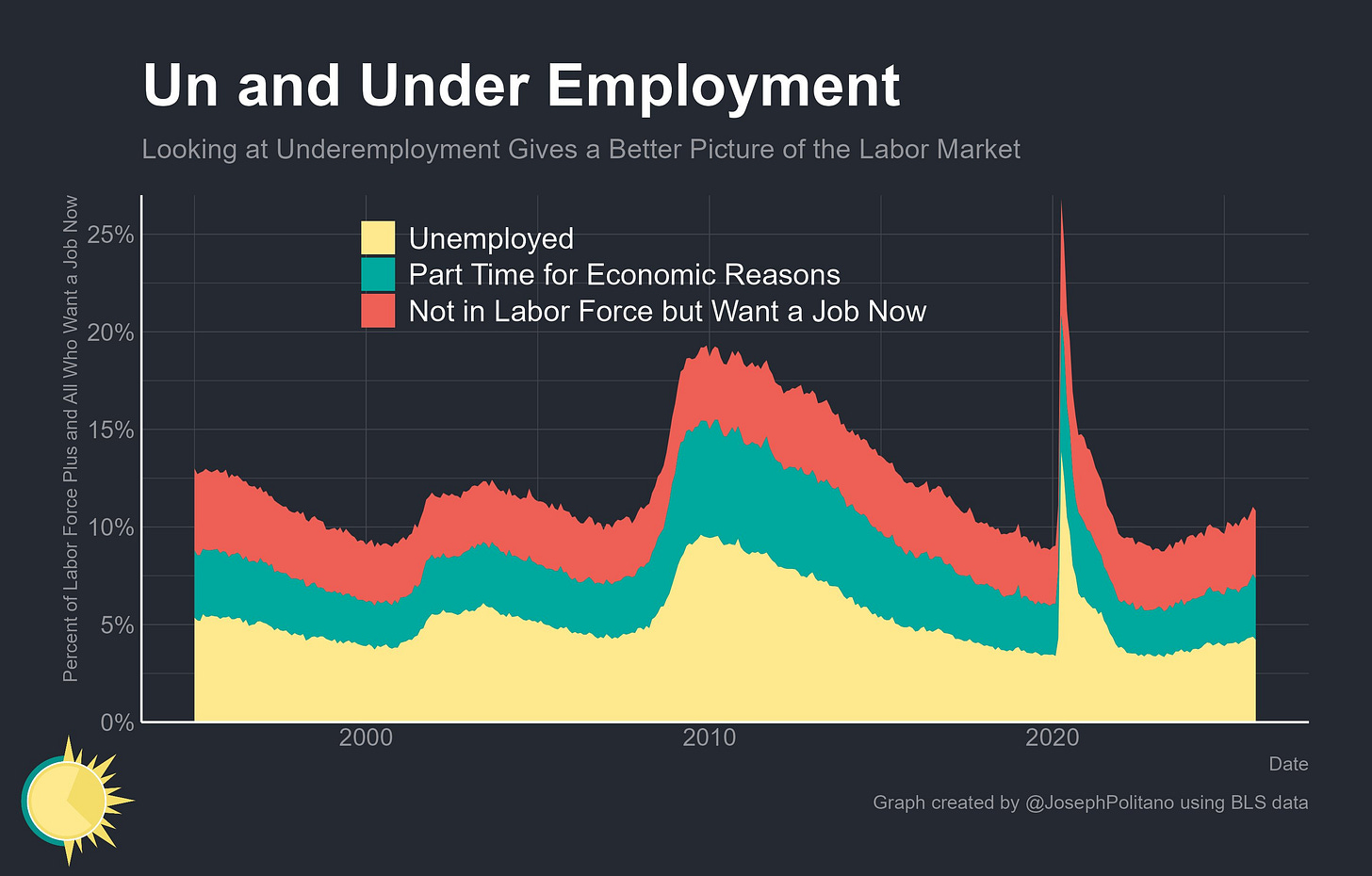

Throughout this period, the unemployment rate has crept up from a low of 3.4% in late 2023 to a recent high of 4.5% set in November 2025. Looking at broader measures of underemployment—including people who want a job but aren’t in the labor force or who are part-time but want a full-time job—the job market is in nearly the worst place since the early pandemic, with roughly 10.8% of the broader labor force looking for more work.

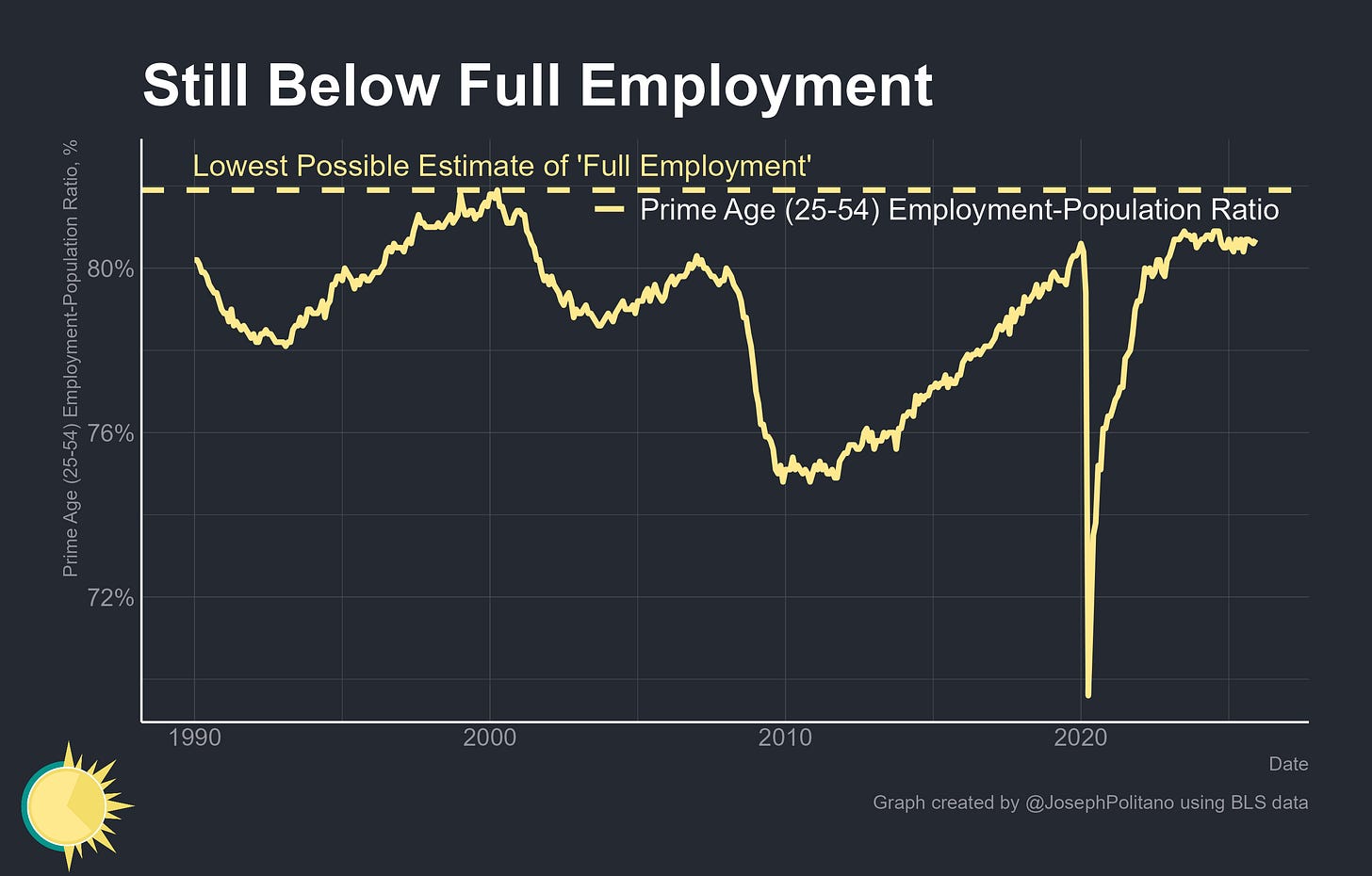

Today’s labor market is perhaps most reminiscent of the “jobless recovery” that characterized the early 1990s or mid-2000s, where employment rates remained stagnant even as overall economic growth had already rebounded. The nearly three-year period from February 2023 to the present is the longest time since those previous “jobless recoveries” where employment rates for prime-age workers have stayed within a one percentage point range, never declining below 80.4% and never rising above 80.9%—despite a more-than-7% increase in US GDP over the same timeframe.

That does not reflect an economy at the apex of full employment, both because America has seen higher employment rates in its own past and because many countries (like Canada, Australia, Japan, and the vast majority of EU member states) all currently have noticeably higher employment rates than the US. But it does reflect a labor market continually stagnating in a “no-hire” equilibrium.

Breaking Down the Job Slowdown

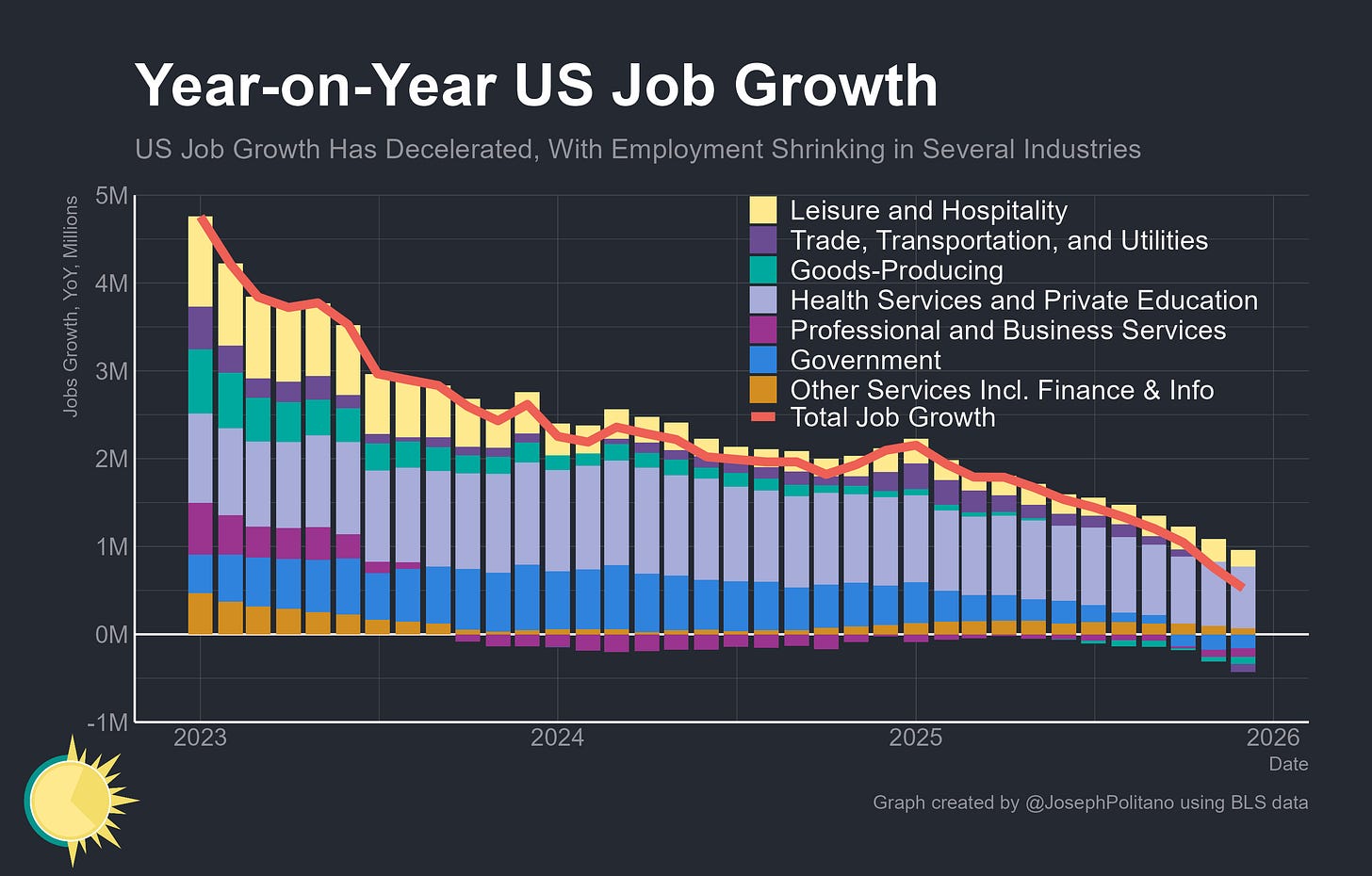

The US has added only 525k jobs over the last year, the slowest pace of job growth since 2020, and a number less than one-third of any period in the late 2010s. That slowdown has been spread across nearly all major industries, with government, professional & business services, goods-producing industries, and the trade, transportation, & utilities super-sectors all losing jobs. The main industry adding jobs is healthcare, which is on a long-run growth trend amidst the rising medical needs of an aging population, and thus is almost always growing faster than the labor market as a whole.

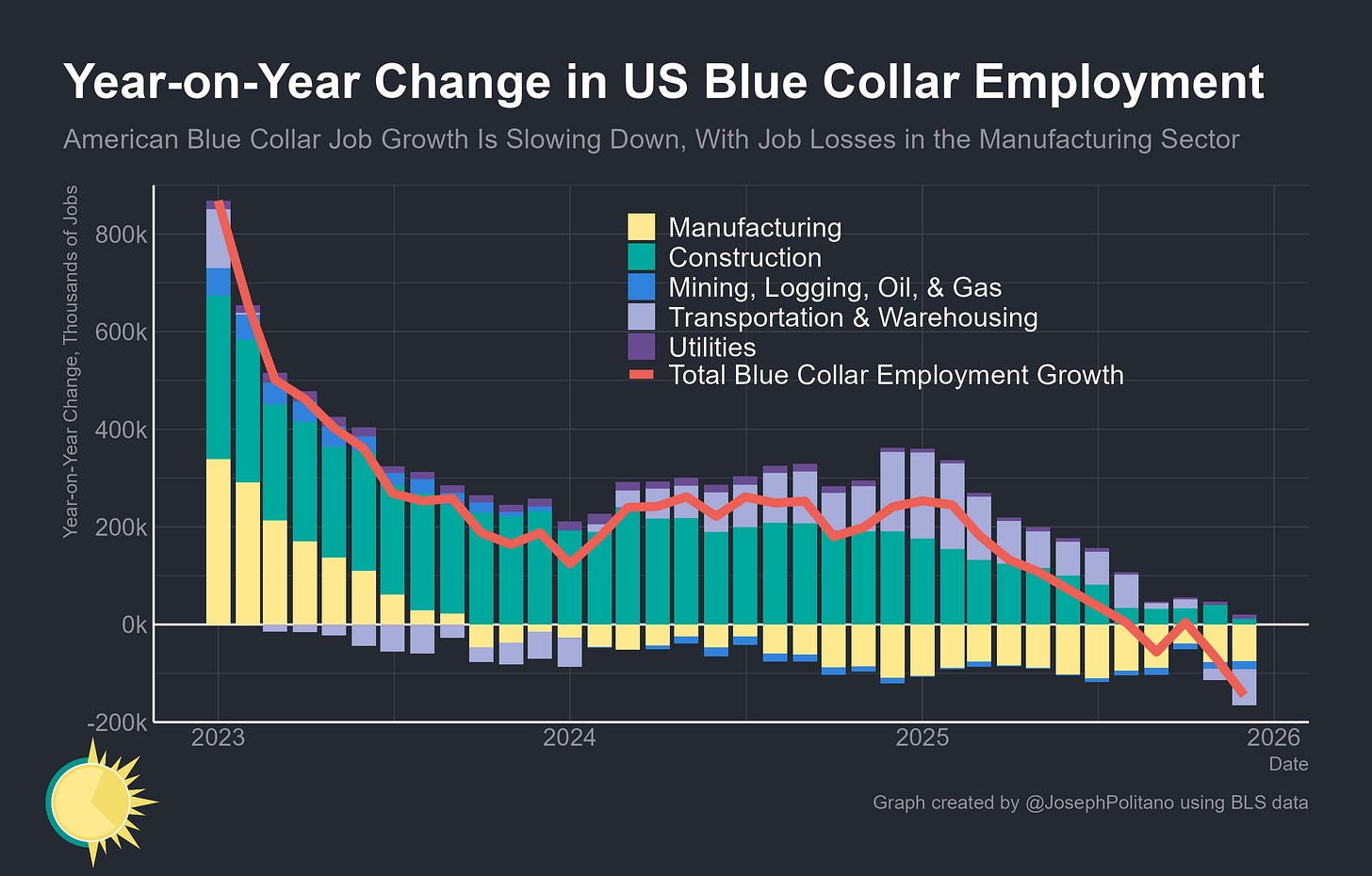

Digging further, the contraction in blue-collar jobs continues to intensify, with their employment levels shrinking by more than 145k over the last year. Job growth in construction has functionally zeroed out, while manufacturing and logistics are each losing tens of thousands of jobs. Warehouses alone have shrunk their workforce by more than 50k over the last year, putting the sector 150k jobs below its early-2022 peak.

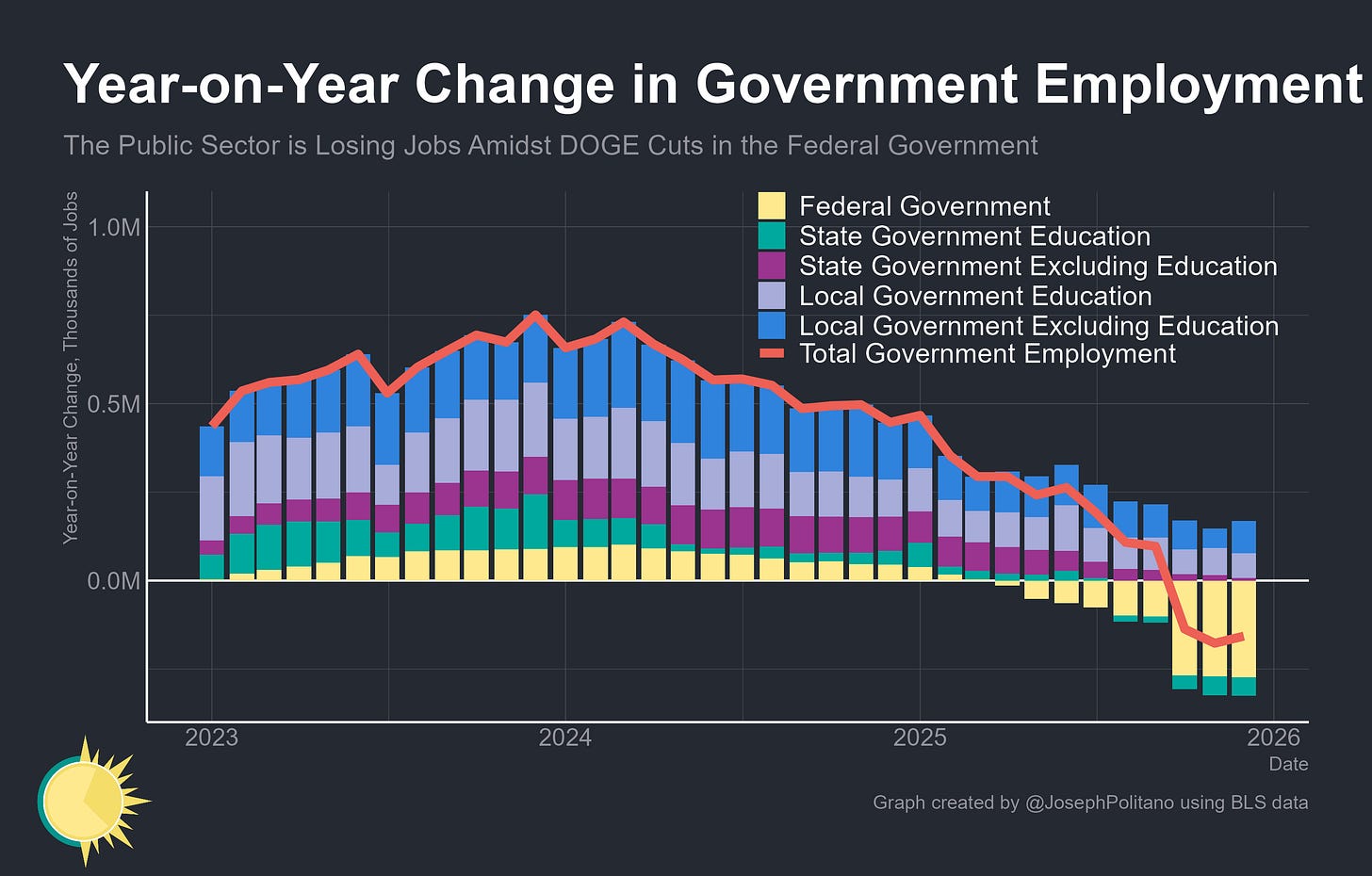

Meanwhile, the US public sector lost more than 157k jobs over the last year, primarily thanks to the DOGE cuts at the federal government. Federal employees represent only 13% of all public-sector jobs, yet the 277k jobs eliminated at the national level, plus the 45k losses at the state level, easily overwhelmed the slow growth at the local level. That local government job growth is roughly evenly split between public K-12 schools and all other local government functions, while state government job losses are concentrated entirely within public Colleges, Universities, & other educational institutions.

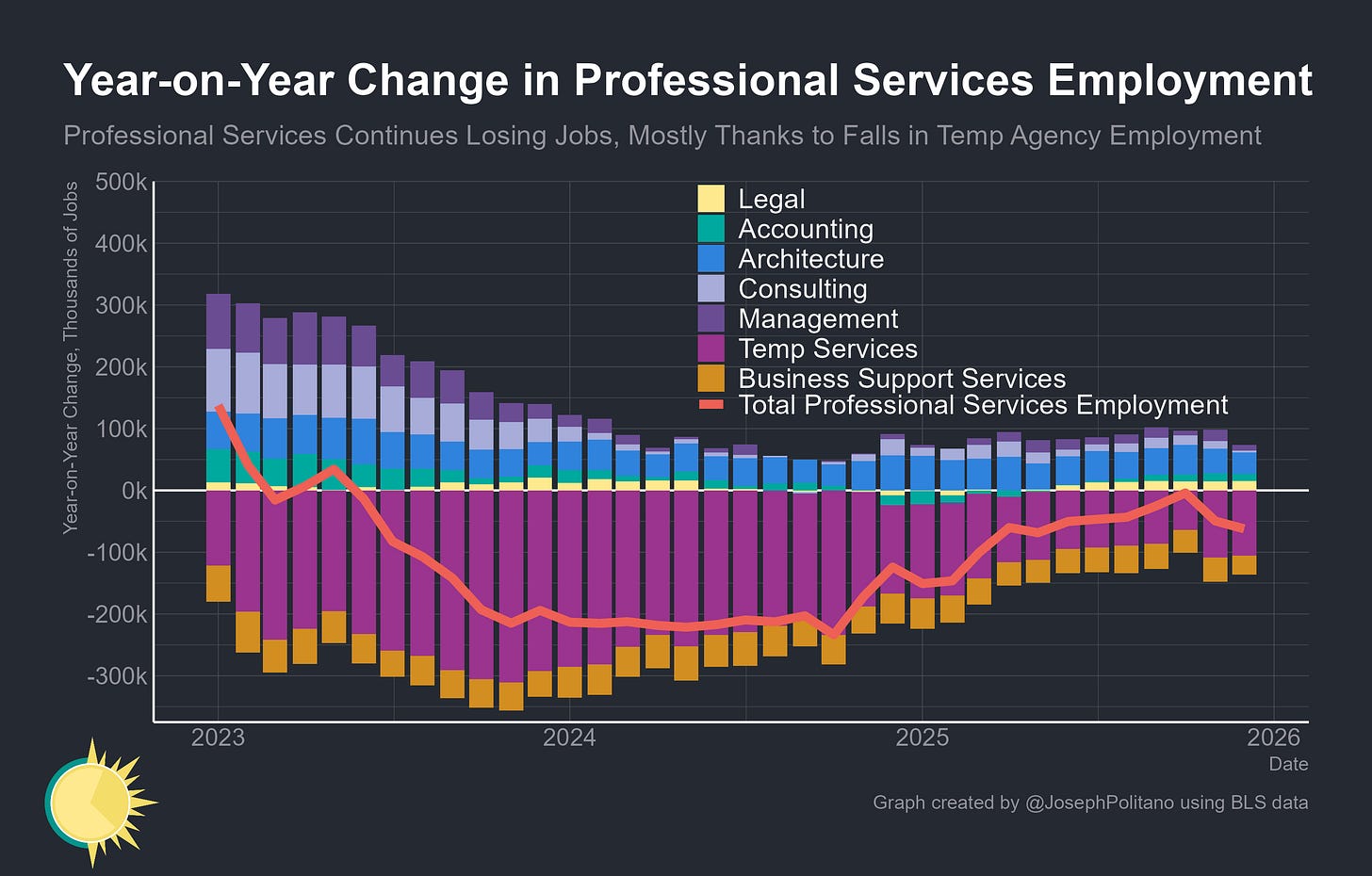

Job growth in professional services industries also remains negative, with employment shrinking by roughly 62k over the last year. The high-paid white-collar sectors like law, accounting, architecture, and management consulting are still adding jobs, just at a much slower rate than pre-COVID, but employment levels at temp agencies and administrative support firms have been continually declining for years now.

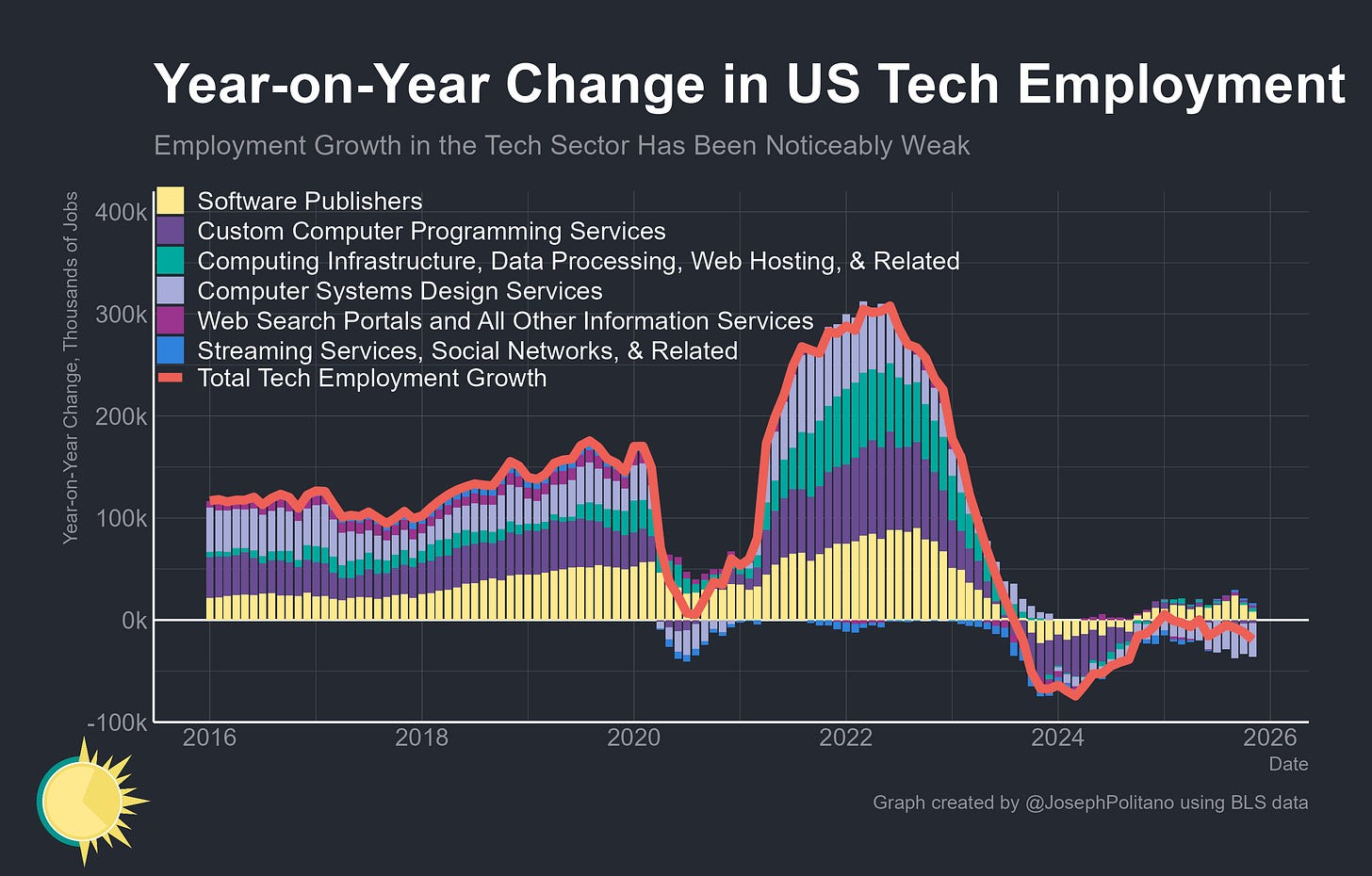

Finally, the tech sector labor market remains extremely weak, with employment shrinking by more than 19k over the last year and down roughly 100k since late 2023. That’s not as bad as the worst of the 2024 tech job market, but it is much worse than the 2022 boom or any period during the 2010s. At least during the 2008 financial crisis, it took only just over a year before tech employment began growing again—today, employment continues falling nearly three years after the beginning of the tech-cession. If this decline persists through 2026, it will beat the dot-com bust for the longest period of tech job market losses in American history.

The Victims of the No-Hire Economy

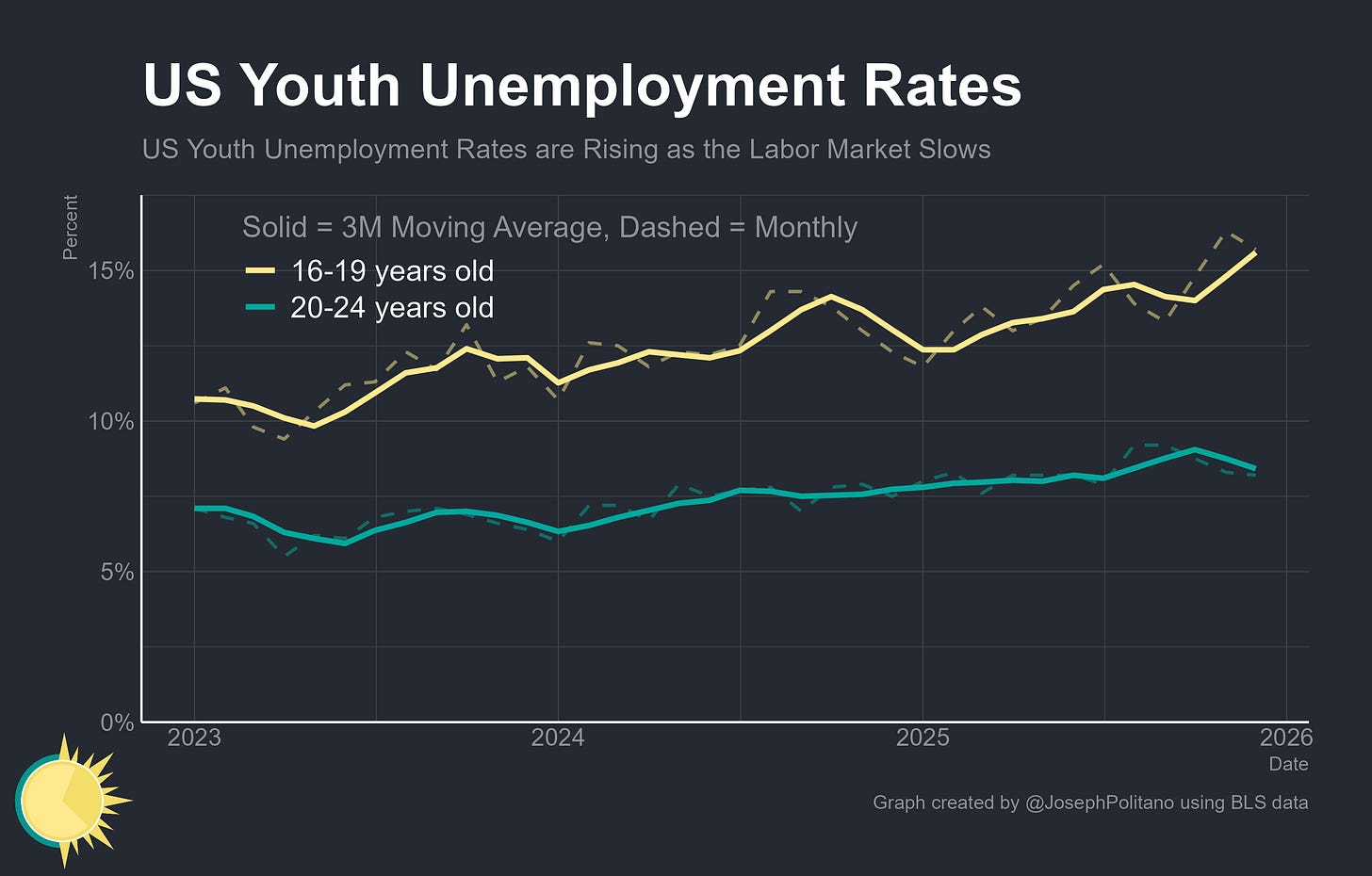

Who has been most affected by this shift to the “no-hire” economy? Established workers with existing jobs can afford to wait out the current labor market slowdown, but early-career workers are finding it harder to land their first jobs, making young people among the hardest hit by today’s job market weakness.

Over the last year, the unemployment rate for teenagers is up by 2.9 percentage points, the unemployment rate for people in their early 20s is up by 0.7 percentage points, but the unemployment rate for those above 25 is up by only 0.2 percentage points. This is also an increasingly bad labor market for recent graduates, as the unemployment rate for young college educated workers is up by a full 1.6 percentage points over the last year. More broadly, the unemployment rate for new labor market entrants (like young adults looking for their first paycheck) and labor market reentrants (like stay-at-home parents going back to office work) are both hovering near their highest levels since 2016.

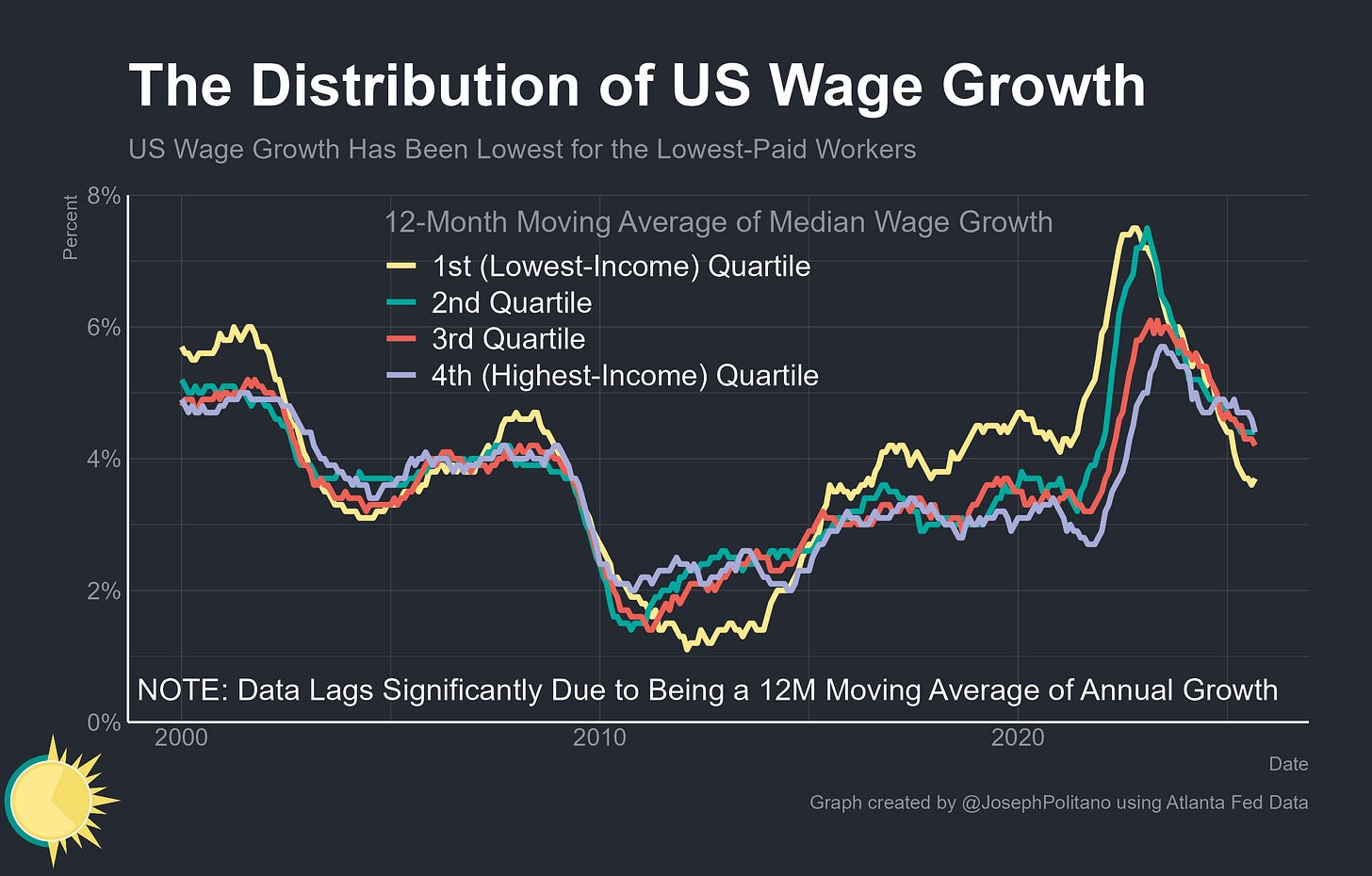

The distribution of wage growth has also radically changed since amidst the “no-hire” economy. From 2021-2022, wage growth for the lowest-paid workers accelerated to the fastest pace in a generation, amidst the Great Reshuffling of those employees into higher-paid fields and companies, and the US economy experienced a rapid decrease in wage inequality as pay growth for the bottom quintile of workers significantly exceeded growth for the top quintile.

Yet wage growth for these lowest-paid workers has ground to a halt over the last two years, and they are now seeing much lower raises than their higher-paid counterparts. In fact, this is now the largest gap in wage growth favoring high earners since the early 2010s, showing just how hard today’s “no-hire” labor market has hit low-income workers.

Conclusions

The 2025 slowdown in job growth is clearly not just a story about the US population shrinking amidst a rapid decline in immigration. We still don’t have good data on how many foreign-born workers have left the US since Trump’s immigration crackdown, but we do know that employment rates for native-born Americans are slowly falling. Nor is this entirely a story about AI-driven disemployment—sectors extremely insulated from computer technology are some of those with the fastest job declines.

Instead, it’s a combination of factors—tighter monetary policy and contractionary fiscal impulses, higher tariffs and lower immigration, technological shifts and rising uncertainty—all chipping away at job growth from different angles. This leaves the labor market on an uneasy precipice, since employment will begin to decline outright unless hiring rates pick up in the near future. In other words, today’s jobless recovery risks hardening into an outright labor market decline.

Hang on! Wasn't Trump going to fix this? He wouldn't have lied to me would he?

Nice read. Really helpful framing with the “no-hire” equilibrium because it matches what I’m hearing anecdotally (few layoffs, but hiring pipelines frozen). Curious what indicator you’d watch as the earliest sign it’s thawing: JOLTS hires rate, temp staffing stabilization, quit rate, or something like small biz hiring intentions?