The Supreme Court Ruled Against Trump's Tariffs. Now What?

Charting the Impact of the Supreme Court Ruling and What Comes Next

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing, you’ll join over 75,000 people who read Apricitas!

Yesterday, the Supreme Court struck down the majority of Trump’s tariffs in the largest legal blow to Trump’s 2nd-term economic policy. “The Framers gave ‘Congress alone’ the power to impose tariffs during peacetime,” said Chief Justice Roberts, “and the foreign affairs implications of tariffs do not make it any more likely that Congress would relinquish its tariff power through vague language, or without careful limits. Accordingly, the President must ‘point to clear congressional authorization’ to justify his extraordinary assertion of that power. He cannot.”

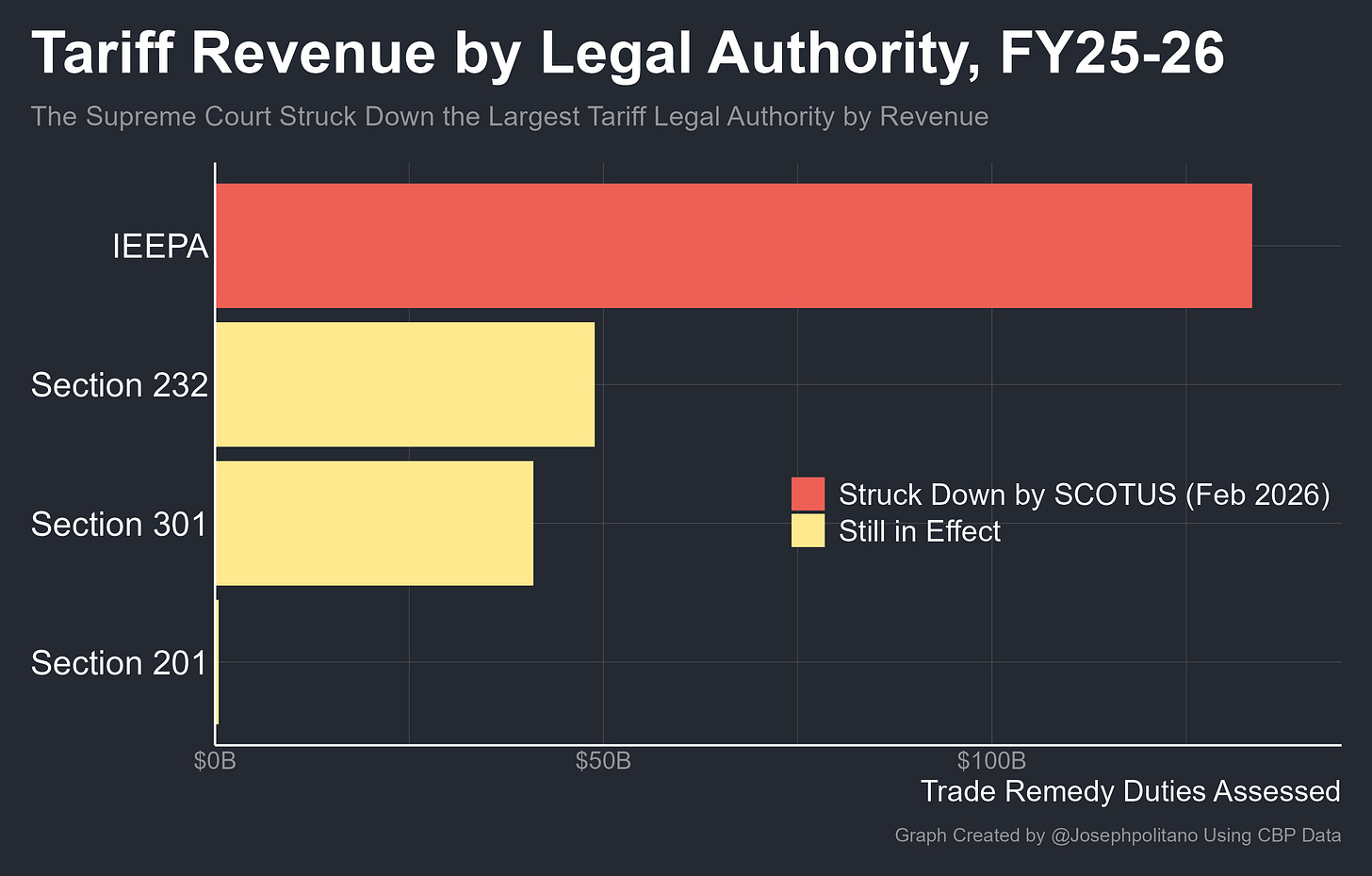

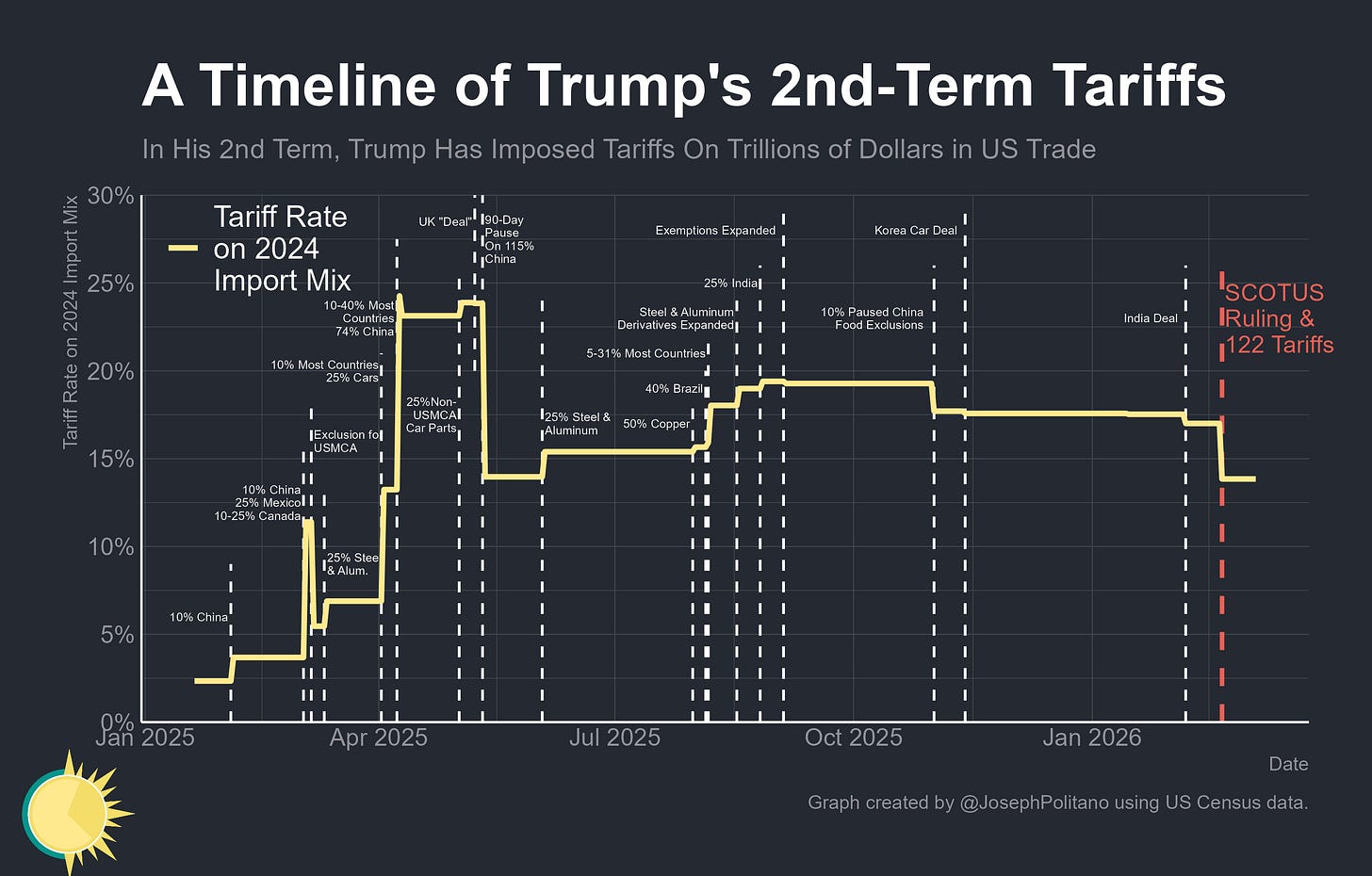

The court thus ruled that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) did not give the president the authority to impose tariffs, meaning all of the country-level tariffs—50% on Brazilian goods, 15% on imports from the EU, etc—have been rendered null and void. The sectoral tariffs on steel, aluminum, cars, furniture, and other goods used the more legally robust Section 232 national security tariff authority from the 1962 Trade Expansion Act and will thus stay in place unchanged, as will the Section 301 tariffs used primarily against China that predate 2025. Yet the country-level tariffs made up the vast majority of Trump’s overall trade war, representing roughly 73% of the total new tariff revenue since he returned to office.

However, the White House and Supreme Court both knew that “many current federal laws continue to grant the President expansive tariff authority” outside of IEEPA, although these pathways come with more time and procedural regulations. Trump responded to the court ruling by immediately invoking one of those other federal laws—Section 122 of the 1974 Trade Act—to impose a 10% baseline tariff to replace the IEEPA tariffs.

Section 122 can only be used for flat tariffs of up to 15%, with no between-country variation allowed. The administration has thus settled on a 10% tariff—the lowest prior country-level tariff rate—while the important tariff exemptions for computers, energy, pharmaceuticals, smartphones, certain foodstuffs, and most USMCA-compliant goods all remained. The net effect is that average US tariff rates will dip roughly 3 percentage points in the wake of this ruling, and no imported goods will see a net increase in tariffs.

Yet Section 122 only allows tariffs to persist for 150 days without congressional authorization, which remains unlikely. It also rests on some shaky legal footing of its own, having been written to empower the President to prevent international payments problems within the fixed exchange rate system that no longer exists. There will certainly be legal challenges to this new Section 122 executive order in time, but before its 150 days are up, the administration could reconstruct much of the pre-ruling tariff regime using the more legally secure sector-level Section 232 “national security” investigations and country-level Section 301 “unfair foreign trade practices” investigations.

Still, this is the most significant restriction on Trump’s trade war capabilities since he retook office. Without IEEPA, the President can no longer wake up in the morning and decide to raise tariffs on Indonesian goods before lunch. The Section 232 and 301 processes are much more bureaucratic, taking months to put together the proper paperwork and giving businesses more ability to directly challenge the specific “national security” or “unfair foreign trade practices” justifications in court. Plus, since the US collected more than $150B in taxes under executive orders now deemed retrospectively illegal, we could see a rather massive refund to importers. It’s an important win in placing some constraints on executive authority and ensuring Congress retains the power of the purse.

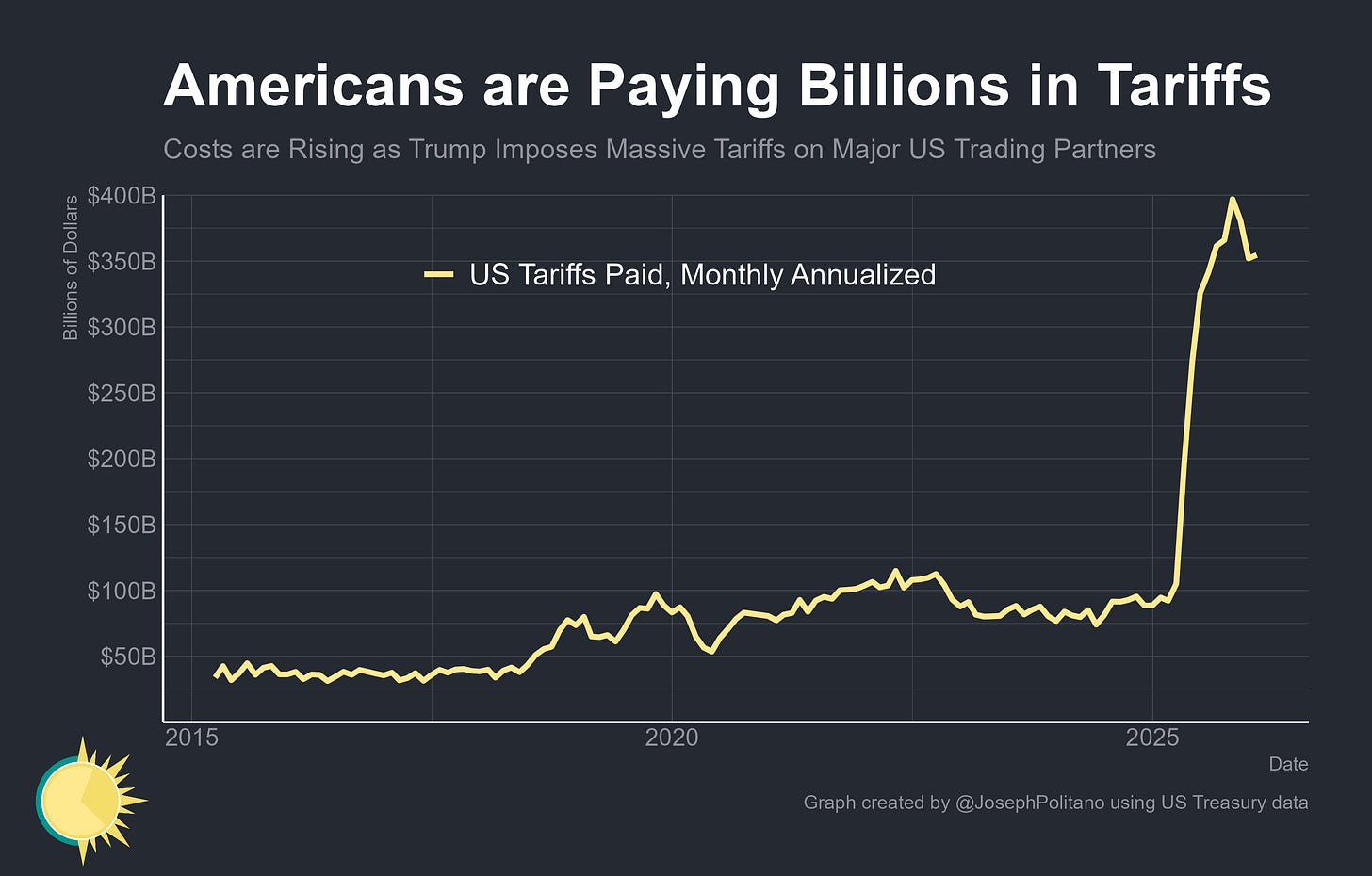

Plus, while US tariffs remain extremely high compared to their pre-Trump equilibrium, they have meaningfully eased even before this week. In November, the US finally exempted coffee, bananas, and other foodstuffs that climatologically cannot be produced at a sufficient scale in the US. The Trump administration had also eased tariffs on Chinese goods down to the lowest level since the start of his second term after negotiations in Beijing. Tariffs on many Indian goods were reduced by 32% in a deal signed in early February. Tariff revenue was running at roughly $400B annualized at its peak, but has slid closer to $350B annualized in the last two months of data, and will likely fall more in the January and February numbers. That’s still much higher than in 2024, but a meaningful retreat in tariff intensity.

The Trump administration could use this ruling as an excuse to continue that partial trade war retreat. Yet in reality, the next few months are more likely to reverse the small amount of trade reliberalization America saw this winter. Lawyers will be working tirelessly to recreate the tariff levels that existed in January. Donald Trump will go back to making ever-changing tariff threats (as of writing, he now claims the 10% 122 tariffs will be raised to 15% “in the next short number of months”, though no formal executive order exists yet, so it’s unclear if this will actually happen or what the details would look like). Even though the Supreme Court has reined in the worst of Trump’s trade war, tariffs and their associated chaos are not going away any time soon.

How Have the Tariffs Been Going?

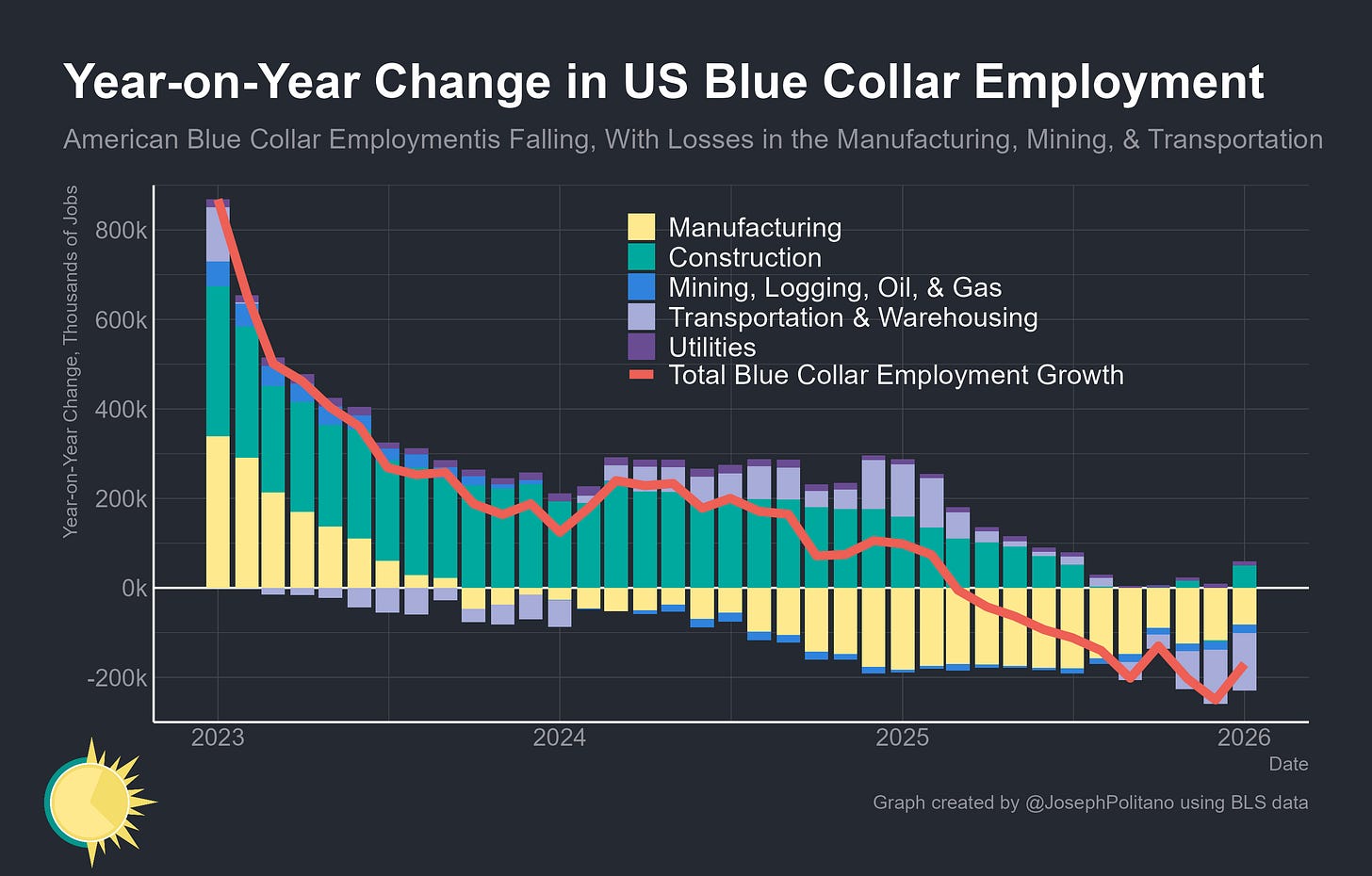

More than a year into the second Trump administration, it’s worth pausing to ask if all these tariffs are even achieving their desired policy outcomes. The ostensible goal was to reshore manufacturing production, create good-paying blue-collar jobs, and close the trade deficit. On the jobs front, the US manufacturing sector continues to lose jobs, now joined by declining employment in transportation and warehousing, while growth in construction has fallen dramatically. For an administration rhetorically tying itself to the fortunes of blue-collar workers, this is an especially dismal outcome.

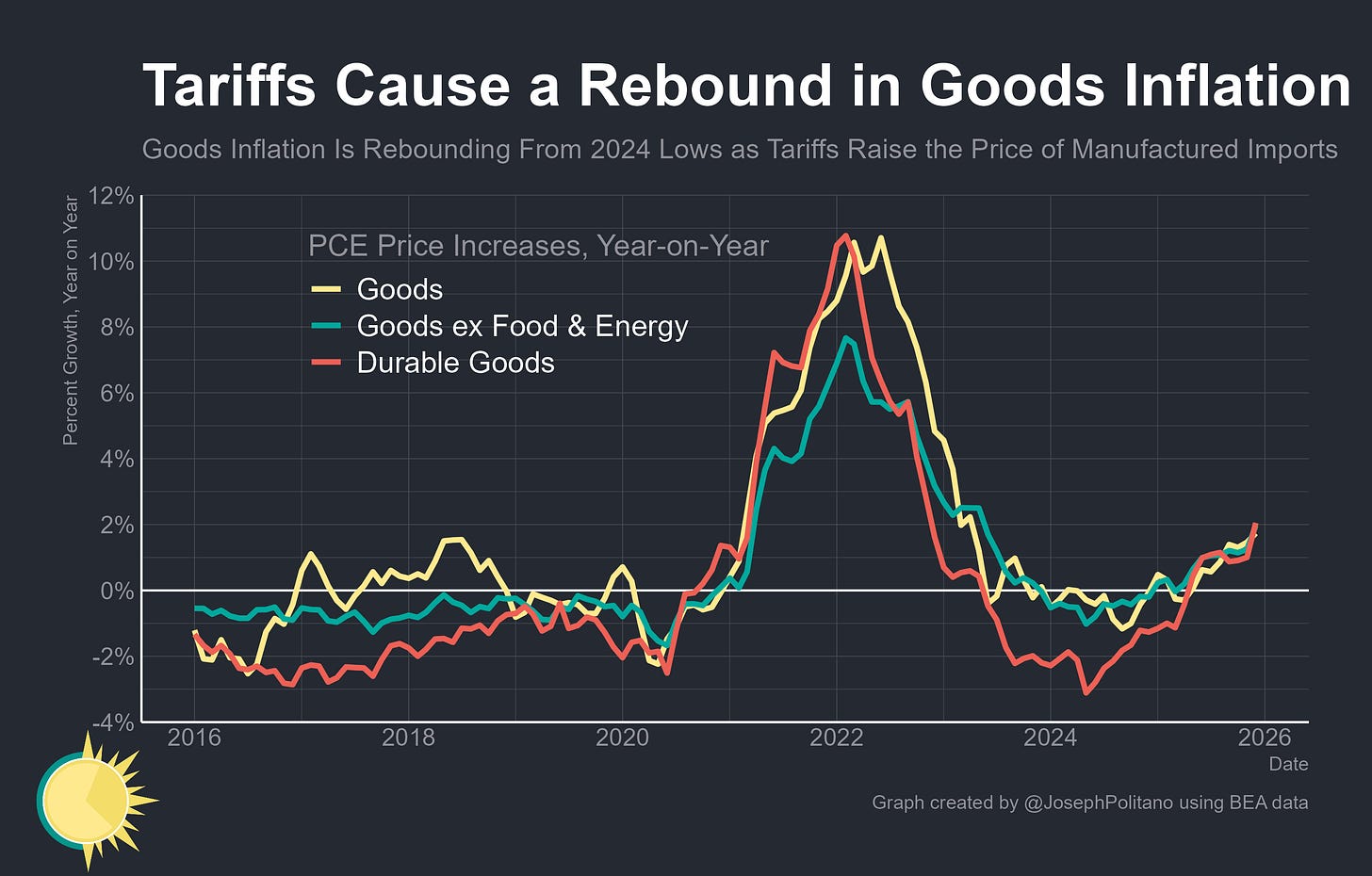

Meanwhile, the massive increase in US tariffs is also driving up prices. Goods prices are up more than 1.7% over the last year, with goods excluding food & energy up 1.9% and durable goods up 2.1%. Those numbers are low compared to the worst of the 2021-2022 inflation surge, when prices were rising more than 6% per year, but they are still meaningfully higher than normal. In fact, manufactured products tend to experience rapid price deflation, so a 2% growth rate is 3-4% above normal levels. Durable goods inflation, for example, is currently running faster than at any point between 1994 and 2020. Americans, not foreigners, and American consumers especially, have been paying the vast majority of the tariffs.

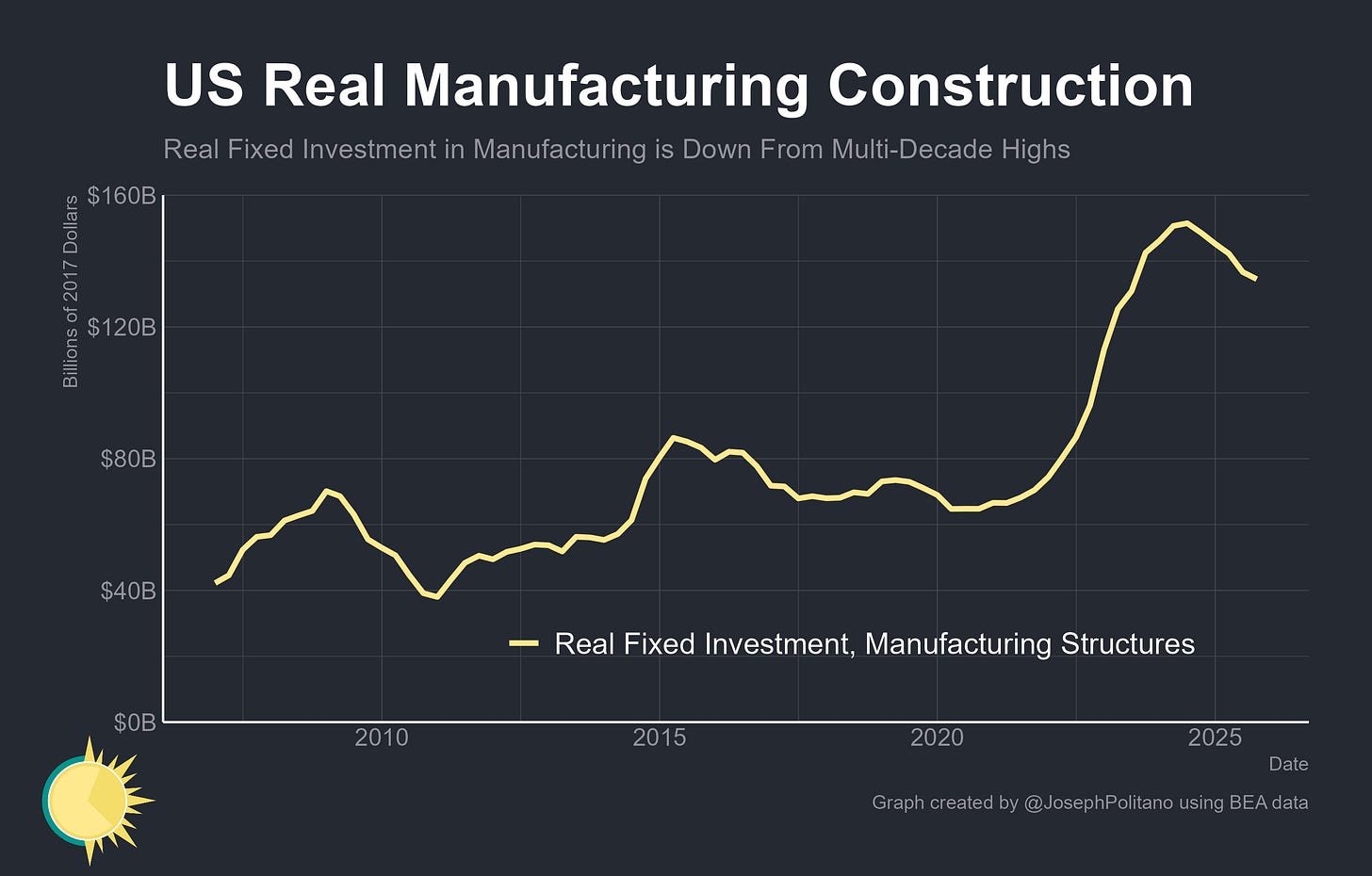

Are the tariffs driving a supposed reindustrialization investment boom? No, real construction of factories has continually declined throughout Trump’s term as CHIPS Act & IRA projects are completed, while tariffs weigh on other sectors. The only place where America undoubtedly has an investment boom is in computers and data centers, which remain completely exempt from Trump’s tariffs.

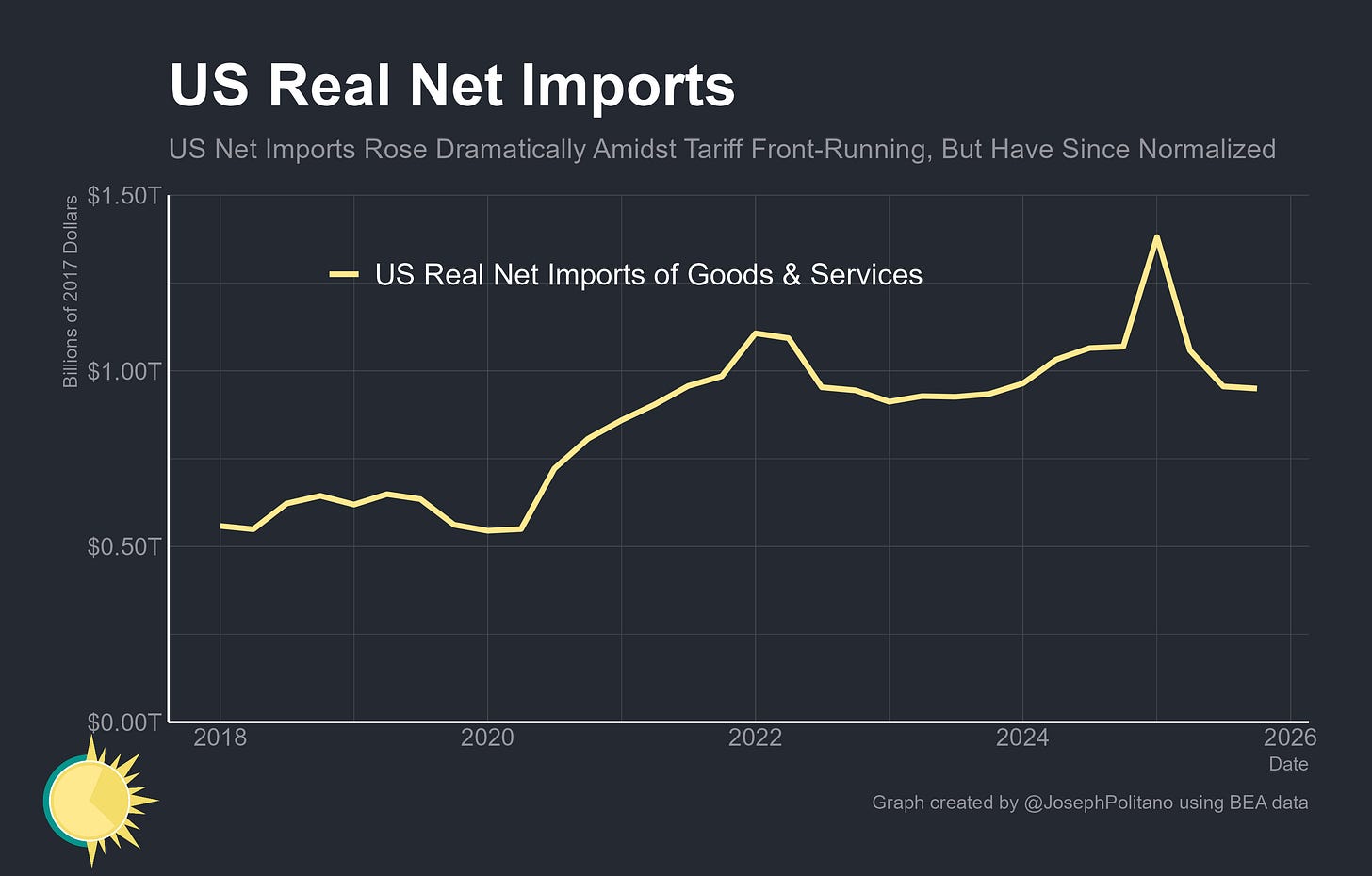

Finally, did the “Liberation Day” tariffs achieve their ostensible purpose of “fixing” the US trade deficit? No, annual net imports of goods & services hit another all-time high in 2025, still well over $1T even after adjusting for inflation. The reduction of net imports in the last three quarters of the year did not make up for the fact that imports surged at the beginning of 2025 as businesses stockpiled ahead of the tariffs. Much of the downward swing in trade is just reduced imports of pharmaceuticals, which remain exempt from tariffs but looked to be under threat at the beginning of last year. Combined, these are not the results of a working policy regime torn apart by one court ruling, but a regressive tax struggling to achieve its supposed economic aims.

Conclusions

Perhaps worst of all, none of the uncertainty that characterized early 2025 trade policy has actually been resolved amidst all this. One year ago, Trump was repeatedly imposing and retracting ruinous tariffs on products from Mexico and Canada, our closest neighbors and some of our largest trading partners, before the President largely backed off in March and just exempted the vast majority of Canadian and Mexican goods. Besides some tweaks to car and metals tariffs, American trade policy with the two countries has been fundamentally unchanged since then. There still is no “deal” with either Mark Carney or Claudia Sheinbaum, even the more vacuous kind signed with the EU or Japan, and there is very little honest effort in the way of negotiations despite how important these countries’ goods are to the US economy.

Instead, Trump is regularly threatening to ground the Canadian-made regional jets that form the backbone of regional carriers, block the Gordie Howe International Bridge built to connect Detroit and Windsor, or impose 100% tariffs on Canadian goods. Many of these threats barely register as news stories in the United States because of their sheer volume and how infrequently Trump actually follows through. Yet he sometimes does, like with the 50% tariffs on Brazilian or Indian goods, making all his threats impossible to completely write off.

How should businesses in countries like the UK, which have supposed “deals” with Trump to keep the tariffs on their goods at only 10%, feel about today’s announcement that all tariffs will eventually go to 15%? Should they ignore it and hope that nobody drafts the executive order, like what happened with the 100% tariffs threatened against Canada? Should they lobby for even more nebulous concessions to keep the tariff rate low, like Switzerland had to do? What should they tell their US business partners or customers? Why should they sign the next “deal” if Trump so quickly reneges on this one?

This ruling should have forced some introspection from the Trump administration. Why did we rest our signature economic policy plans on shaky legal theories? Why has it not achieved its desired policy aims? Why are we forced to exempt the vast majority of imports from tariffs to keep the economy functioning? Why can’t we decide on the right tariff rate and keep it there for an extended period of time? Instead, they’re likely to retreat back into the tariff chaos that has dragged down the economy throughout the last year.

Really solid commentary, analysis. Much appreciated!

Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 (19 USCA 2132) provides the President authority to address ‘balance of payments” 9not current account) imbalances if such imbalances threaten an”imminent and significant” depreciation/appreciation of the dollar. The provisions related to the across the board tariff increases states the balance of payment deficits must be such that the dollar is likely to experience a significant depreciation. I am not sure folks have actually read the statute since no one seems to be addressing whether these conditions are met.